Monkey Moms Act Like Human Moms

The intense, special exchanges that human mothers share with their newborn infants might have deep roots all the way back in monkeys.

Rhesus macaques and their offspring interact in the first month of life in ways much like what humans often do, scientists now suggest.

"What does a mother or father do when looking at their own baby?" asked researcher Pier Francesco Ferrari, a behavioral biologist and neuroscientist at the University of Parma in Italy. "They smile at them and exaggerate their gestures, modify their voice pitch — so-called 'motherese' — and kiss them. What we found in mother macaques is very similar — they exaggerate their gestures, 'kiss' their baby, and have sustained mutual gaze."

Past research has shown these emotional interactions go both ways in humans — newborns are sensitive to their mother's expressions, movements, and voice, and engage their parents in much the same way. For years, these capacities were basically considered unique to humans, although perhaps shared to some extent with chimpanzees.

Now Ferrari and his colleagues extend these skills to macaques, "suggesting the origins of these behaviors actually goes way back," he told LiveScience. (Rhesus monkey ancestors diverged from those of humans roughly 25 million years ago, while chimpanzees diverged from our lineage 6 million years ago.)

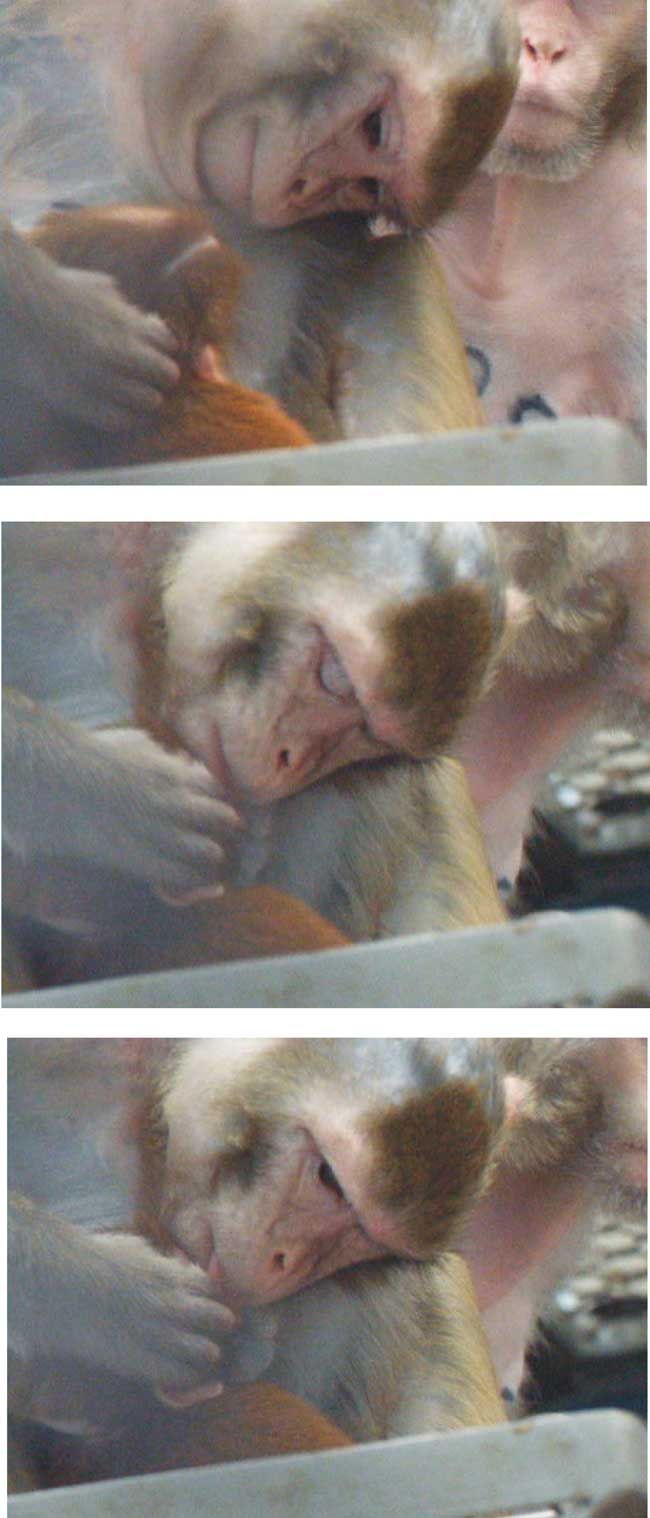

The scientists closely observed 14 mother-infant pairs for the first two months of the babies' lives. Mother macaques and their infants spent more time gazing at each other than at other monkeys. The researches also found that mothers more often smacked their lips at their infants, a gesture that the infants often imitated back to their mothers, suggesting that infant monkeys may have a rich internal world that we are only now beginning to see.

Moreover, Ferrari and his colleagues saw mothers actively searching for the infant's gaze, sometimes holding the infant's head and gently pulling it towards her face. In other instances, when the babies were physically separated from their mothers, the parent moved her face very close to that of the offspring, sometimes lowering her head and bouncing it in front of the youngster.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Intriguingly, these exchanges virtually disappeared when infants turned about one month old.

"It's quite puzzling," Ferrari said, "but we should consider that macaque development is much faster that of humans. Motor competences of a two-week-old macaque could be compared to an eight- to twelve-month-old human infant. Thus, independence from the mother occurs very early. What happens next in the first and second month of life is that infants become more interested in interacting with their same-age peers."

This discovery suggests that by studying monkeys, scientists might get insights into the evolution of parental care and infant development in humans.

"These types of interactions are the way we learn to be sensitive to others' needs," Ferrari said.

The scientists detailed their findings online October 8 in the journal Current Biology.

- Why Are 'Momma' and 'Dada' a Baby's First Words?

- Top 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- 10 Amazing Things You Didnt Know About Animal