Chinese Brain-Imaging Device a Suspected Copy of U.S. Device

A Chinese team's brain imaging device has come under question from developers of a U.S. device who say it's a near duplicate of theirs, LiveScience has learned. An article on the Chinese device was published in the prestigious journal Science, and the U.S. researchers are preparing a formal letter to the journal in response.

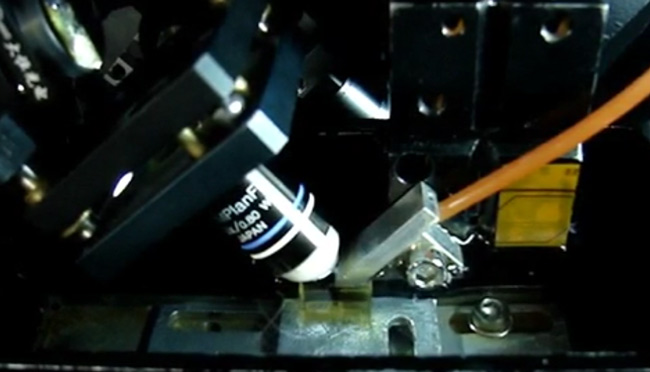

According to the report appearing in the Nov. 4 online edition of Science, the Chinese imaging device used a diamond knife to shave ribbons off a centimeter-size mouse brain and imaged the slices during the process. That allowed the Chinese team to create a 3-D map of the brain that revealed details as small as the axons and dendrites — the circuitry that transmits signals between brain cells — as a step in the race to map the connections in the brain.

LiveScience contacted Yoonsuck Choe, director of the Brain Networks Laboratory at Texas A&M University, for comment on the Chinese device the day the paper was published, and the inquiry by the website immediately set off alarms.

((ImgTag||right|null|null|null|false))

Choe's lab, which had developed its own knife-edge scanning microscope, or KESM, said today (Nov. 15) it will not officially comment in detail because it is preparing an official "Letter to Science" submission to formally alert the editors of the journal.

The U.S. researchers have already contacted the journal with their concerns, and a Science representative told LiveScience that the matter is being taken seriously.

Choe said he suspects the Chinese researchers copied the KESM design to create their own version of the brain imaging device. Due to LiveScience's early involvement in the controversy, the website has been able to reconstruct some background on how the U.S. brain imaging device could have been copied.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

How it went down

Choe's lab started the development of its KESM almost a decade ago. The main architect behind the instrument was Bruce McCormick (1928-2007), a computer scientist at Texas A&M University.

The Chinese group in question hails from the Britton Chance Center for Biomedical Photonics at Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics–Huazhong University of Science and Technology, in China.

Choe possesses an e-mail that shows the same Chinese lab previously asking the main engineering contractor for Choe's lab, Micro Star Technologies, for a custom-made diamond knife. The knife forms a key part of the KESM, along with commercially available components such as the camera.

Micro Star Technologies refused the Chinese request.

Now made in China

Despite Micro Star's refusal, Choe said he believes the Chinese team may have gotten enough information about KESM from detailed online technical reports and a Journal of Microscopy article to manufacture a nearly exact replica.

The Chinese researchers, led by Qingming Luo, named their device the Micro-Optical Sectioning Tomography, or MOST. They did not respond to an e-mail request for an interview from LiveScience at the time they announced the device.

Initial e-mail requests for comment by the Chinese team were not returned.

Choe said technical specs and details for MOST make the device an almost perfect replica of KESM. The Chinese researchers gave only passing mention to the U.S. team in the Science article.

Suspicions first arose when LiveScience contacted Sebastian Seung, a computational neuroscientist at MIT. He leads a collaborative effort to speed up the mapping of the brain's wiring diagrams, known as connectomes.

"I just looked at it briefly, but it doesn't seem novel," Seung said in an e-mail on the morning of Nov. 4. "Isn't it equivalent to this?"

"This" referred to the KESM developed by Choe's lab. Seung then suggested contacting Choe.

A tale of two labs

Choe and his colleagues e-mailed their concerns to Science on the night of Nov. 4, along with the technical information and publication references to support those concerns.

The journal confirmed to LiveScience that it had received the concerns of Choe's lab and that the Science editorial department would take them seriously.

"It's so preliminary right now and we don't have the facts — we weren't involved with [what] happened between these researchers," said Kathleen Wren, Science press package director, in a phone interview Nov. 5. "Certainly our editorial department will evaluate this, and the next step is to make sure they have all the relevant facts."

The Science editors eventually responded on Nov. 12 by telling Choe's Texas A&M group that it could either contact the Chinese researchers directly or write a formal "Letter to Science" for publication in the journal. The U.S. researchers are currently preparing their official letter to the journal.

"Science is a self-correcting enterprise, and the publication of letters to the editor, technical comments, and other responses to original research, including other research papers, are a routine part of the scientific process," Wren said in an e-mail to LiveScience.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- China Stakes its Claim as U.S. Rival in Innovation

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind