Mine! How Selfishness Can Benefit Society

Listen up, do-gooders: Your selfish counterparts, often relegated to the lower rungs of society, can actually benefit the group, a new study suggests.

While the results are based on lab experiments of yeast cells, the researchers suggest similar dynamics may play out in humans. Their message: Scientists should not take for granted the long-held assumption that cooperation is best for everyone.

"It's a paper that says, 'Here's a stack of cards, and we just pulled a card away from right at the base of this house.' One of the foundations on which a lot of the cooperation theory has been built has just been taken away," said study researcher Laurence D. Hurst of the University of Bath, in England.

Computer models used for studying cooperation, for instance, have the built-in assumption that cooperative individuals benefit the group while selfishness does not.

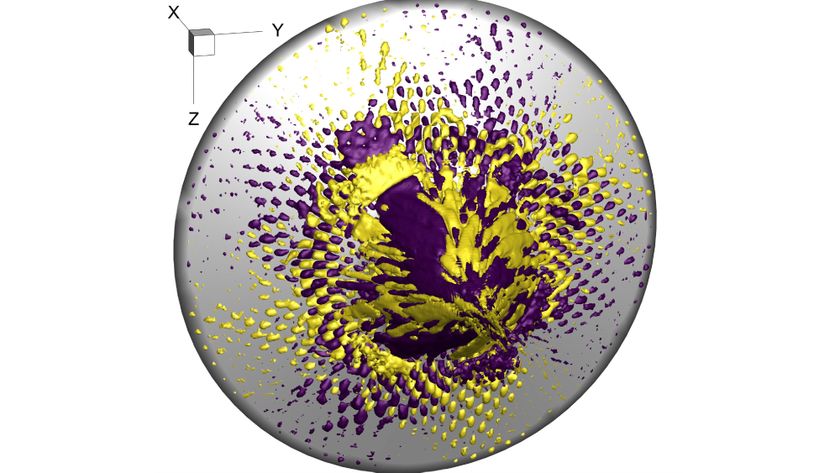

Hurst, with Ivana Gudelj of the Imperial College London and their colleagues, worked with two strains of yeast, "cheaters" and "cooperators." The cooperating yeast cells produce a protein that breaks down sucrose, which is tough for the cells to eat, into glucose and fructose, which are easier to eat and convert to growth. The cheaters don't produce the protein (called invertase) but still partake in eating the broken-down sugars.

After giving sucrose to yeast, the researchers were floored to find the populations that included a mix of both givers and takers grew more than those with only the straight shooters. The team also found similar results using a computer model of the scenarios.

Here's what they think is going on: Since the cooperators are the ones churning out the broken-down sugars, it is nearest to them, and they pay no mind to efficiency.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The cooperators "are sitting in a puddle of their own self-made glucose, using it very badly," Hurst told LiveScience. "Because they see so much of it, they're not converting it very efficiently into growth.

"Those who see much less glucose do much better with it, make more growth with the food they're given."

Having cheats around makes resources more scarce, keeping the cooperators from wasting their food. The same may hold for us, Hurst said. Individuals with, say, lots of money and lots of food choices nearby would be more apt to leave that half burger uneaten than would someone with fewer resources.

Hurst said he hopes researchers look into the phenomenon in human groups.

Another piece to the puzzle involves the turn-on switch for invertase production. The cooperating yeast cells rely on glucose levels (the broken-down sugars) to regulate when and how much of the protein gets released, even when there's no sucrose around.

"They're making this enzyme but there's nothing to break down so they suffer a cost for doing it anyway," Hurst said.

The study, to be published next week in the online journal PLoS Biology, was funded by the Royal Society, Mexico's National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt), and Great Britain's Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.