Insects Inspire Flying Robots

This ScienceLives article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Itai Cohen studies soft, condensed matter. The research topics he investigates range from flows in gels and pastes, to tissue mechanics, to animal movement. He is obsessed with motion. Currently a professor in the Cornell Physics department, he recently helped discover that the crystalline silicon sheets in semiconductors, the foundation of modern computers, might be grown more smoothly by managing the random darting motions of atomic particles that control crystal growth. Electrons travel better in smoother materials, leading to faster electronics and greater energy efficiency. You can read more about the work, just one of the projects Cohen has pursued in recent years, here and you can read his answers to the ScienceLives 10 Questions below.

Name: Itai Cohen Age: 36 Institution: Cornell University Field of Study: Physics

What inspired you to choose this field of study? What inspired me to pursue this career is the feeling I get when I make a discovery. There is something awesome about sitting there with your apparatus and seeing something that no one else in the world has ever seen. These moments are full of giddy anticipation. It’s as though you had some juicy piece of gossip and you are the reporter that gets to reveal this secret to the world.

What is the best piece of advice you ever received? There was a line in “Star Trek the Next Generation” that I always remember. Q appears on the Enterprise and tells Captain Picard that the fate of humanity depends on how he and the crew of the Enterprise perform on their next mission. Number 1 then asks Picard what he would like them to do differently to which Picard answers: “Nothing. If we're going to be damned, let's be damned for what we really are.”

What was your first scientific experiment as a child? I devised an experiment to determine whether or not there was a tooth fairy. At night I had gone to bed with a tooth under my pillow and when I woke up sure enough the tooth was gone and a crisp dollar bill was lying in its place. I took the dollar bill and slid it between the sheet and the mattress. I then went downstairs and in a really whiney voice explained to my parents that the tooth fairy had stolen my tooth and didn’t leave me anything in return. At that point my dad ran up the stairs and searched all around my mattress muttering, “I know I put it here somewhere.”

Case closed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is your favorite thing about being a scientist or researcher? There is nothing close to the feeling you get when you make a discovery. When I was a graduate student and a postdoc, I was the first person to be in on the discovery. Now that I am an advisor, I get to be the second person to be let in on the secret. I also get to see the sense of satisfaction on my students’ faces. Being able to share that experience with my students and enabling them to continue to make new discoveries is wonderful.

What is the most important characteristic a scientist must demonstrate in order to be an effective scientist? What is nice about this field is that it can accommodate all sorts of different styles and personalities. The most important thing for me personally is that my research be creative and beautiful. There are many successful scientists, however, who are just great at doing repetitive studies, or slogging through difficult calculations that many would consider less creative. We need these different types of personalities and methodologies to advance the field as a whole.

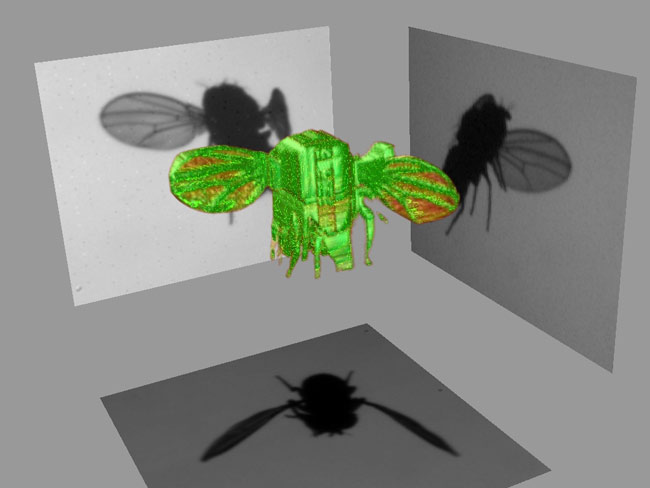

What are the societal benefits of your research? My research area is fairly applied. Our work on droplet breakup was funded by P&G, because they want to know how to concentrate detergents and still have the soap disperse uniformly. Our work on colloidal crystallization may have implications for growing thinner, more defect-free films. Our work on insect flight may inspire simple solutions to the control of flying robots. Our work on cartilage may help in determining how diseases such as osteoarthritis progress. In addition, I am helping to develop the next generation of scientists so that they can tackle the problems of tomorrow.

Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher? My Ph.D. advisor Sid Nagel. You don’t go through six years of intense discussions day after day without picking something up. Thanks Sid.

What about your field or being a scientist do you think would surprise people the most? I think most people have this idea that science is about going to the lab, measuring something, and then reporting that measurement. There is no sense that science is about creatively interpreting your data and trying to squeeze some sort of picture out of it that corresponds as closely as possible to what is really happening. When we take a video of a fly in mid air, we still need to do some pretty creative footwork to figure out what it is doing in 3D. All we have to work with is a 2D representation of the insect. Once we have a faithful representation of the 3D motion we still need to figure out what it means. All of these steps demand an incredible amount of creativity and ingenuity. People do get the sense that science is hard but they think it is hard because of the math. The math is easy. Coming up with creative solutions to these experimental challenges is hard.

If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be? My artwork. We tend to take photographs of our experimental phenomena. Whether it’s a drop dripping from a faucet, or a fly hovering in the air, the beauty expressed by these images represents the reason I am in this field.

What music do you play most often in your lab or car? My favorite artist is Leonard Cohen. When that’s not available I listen to Weird Al.

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the ScienceLives archive.