Underwater Volcano Erupts on Video

New videos show the first ever observations of deep submarine volcanic eruptions.

Most of the Earth's volcanic activity happens underwater, anywhere from the surface all the way down to depths greater than 2.5 miles.

However, this underwater activity has rarely been seen directly. Previous accounts were either after the eruptions or by surface vessels that couldn't get close enough to the action.

Submerged fireworks

In March 2004, a team of NOAA scientists sent a remotely operated research submarine, named ROPOS to find some hot vents along the Mariana Arc volcanic chain.

"What we found was an eruption in progress," said Verena Tunnicliffe, a biologist at University of Victoria, Canada. "We found this big pit with rocks and molten sulfur flying out. And we were sitting at the edge of this pit."

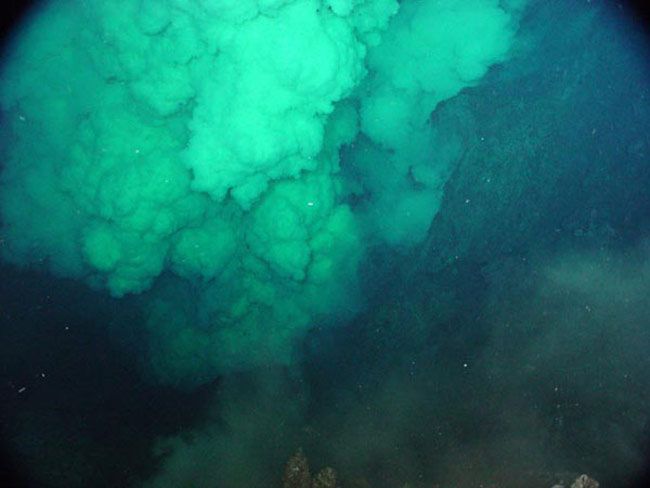

Pulsating plumes of opaque yellowish ash containing droplets of sulfur started surging out of a feature called Brimstone Pit, close to the summit of a volcano named NW Rota-1, 60 miles northwest of the island of Rota in the North Pacific Ocean, at 1,820 feet below the water surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It wasn't until the scientists brought the vehicle to surface that they saw the dime-sized golden droplets covering the exterior of ROPOS. The results are detailed in the May 25 issue of the journal Nature.

Moving plates

The Earth's outer layer is made up of plates, each moving about four inches a year. Earth's molten lava rises and pushes Earth's plates apart in the middle of the oceans.

When an oceanic plate slides under a continental plate, it creates a subduction zone. The rock is once again heated as it goes down into the Earth, and magma again rises to form volcanoes.

While the oceanic Pacific Plate moves west towards Japan, the Philippines Plate moves eastward towards Hawaii. The Pacific Plate is being subducted and gases and molten lava are coming up through the Philippines Plate, Tunnicliffe explained.

This causes magma and other materials to spew out in volcanic eruptions at sites like Brimstone Pit.

The return

In October 2005, the scientists sent another vehicle, the Hyper-Dolphin, to the site to Brimstone Pit and found that it's still active and spewing out magma ash.

In their latest expedition, which started in April 2006 and recently ended, the team's third remotely operated vehicle to visit the site, Jason II, was bombarded by volcanic bombs.

"Volcanoes put out magma in different forms," said Robert Embley, a geophysicist at the NOAA Vents Program. "In water they solidify. The smaller ones are ash and the bigger ones are bombs."

But more importantly, Jason II also showed that the volcano is still active and ongoing.

On Jason II's first dive, the team was unable to find Brimstone Pit because a volcanic fog made it hard to see. In the second dive, the fog had dissipated and the scientists noticed that part of the volcano had fallen off since their last visit.

"Something happened there before we got there," Embley told LiveScience.

The slow-moving cloud of white smoke soon started becoming more active. The cloud and bubbles started escalating and pulsing like never before, suggesting the volcano continually erupts in cycles of varying activity.

"In some ways we were able to see what was happening underwater better than is possible on land—because the pressure of 560 meters (1,837 feet) of water dampened the power of the explosive eruptions and so we could observe what was going on from very close up, which is impossible on land," said study team member William Chadwick of Oregon State University.

Acid water

When the area water was sampled, even when there was no activity, it was found to be very acidic from the high concentration of sulfur.

"Sulfur dioxide is one of the main gases that come out of arc volcanoes," Chadwick said. "When the sulfur dioxide mixes with seawater, it produces sulfuric acid and sulfur droplets. This makes the volcanic plumes very acidic, like stomach acid."

This and the recurrent rain of molten sulfur and ash mean that the sides of the volcano are inhospitable to all but a handful of hardy organisms such as shrimp extreme microbes that huddle in mats.