Dead Zones: Devil in the Deep Blue Sea

Brian Palmer covers daily environmental news for OnEarth. His science writing has appeared in Slate, The Washington Post, the New York Times, and many other publications. This article first appeared in the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) publication OnEarth. Palmer contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

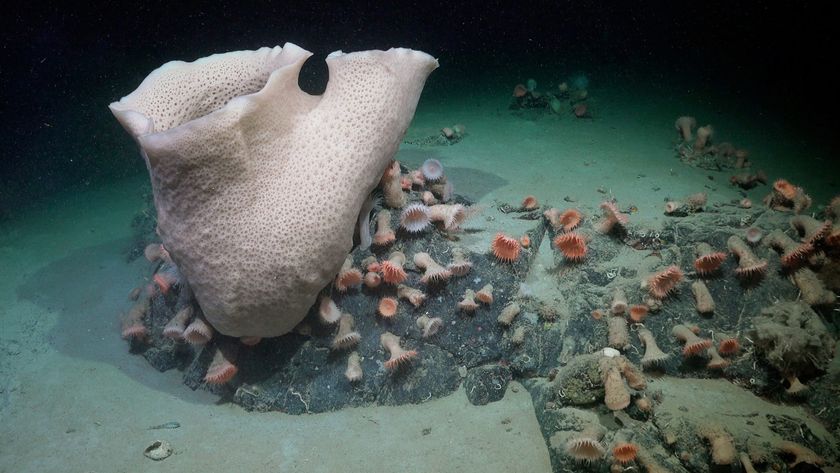

A stretch of the Gulf of Mexico spanning more than 5,000 square miles along the Louisiana coast is nearly devoid of marine life this summer, according to a study from the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium released this week. Caused largely by nutrient runoff from farm fertilizer, this oxygen-deprived "dead zone" is approximately the size of Connecticut. Although slightly smaller than last summer's edition, the Gulf dead zone is still touted by some as the largest in the United States and costs $82 million annually in diminished tourism and fishing yield.

Which makes you wonder…

How many other dead zones are out there?

There are probably around 200 dead zones in U.S. waters, alone. After reviewing the academic literature on "hypoxic zones" in 2012, Robert Diaz, professor emeritus at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at the College of William and Mary, identified 166 reports of dead zones in the country. Coastal waters contain the vast majority, though some exist in inland waterways. A handful of the 166 dead zones have since bounced back through improved management of sewage and agricultural runoff, but as fertilizer use and factory farming increase, the United States is creating dead zones faster than nature can recover.

There are more than 400 known dead zones worldwide, covering about 1 percent of the area along the continental shelves. That number is almost certainly a vast undercount, however, since researchers have yet to adequately study large parts of Africa, South America and Asia. Diaz estimates that a more accurate count is 1,000-plus dead zones, globally.

What causes dead zones?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Agricultural practices are the biggest culprit for dead zones in the United States and Europe. Rains wash excess fertilizer from farms into interior waterways, which eventually empty into the ocean. At the mouths of rivers, such as the Mississippi, the glut of phosphorous and nitrogen intended for human crops instead feeds marine phytoplankton. A phytoplanktonic surge leads to a boom in bacteria, which feed on the plankton and consume oxygen as part of their respiration. That leaves very little dissolved oxygen in the subsurface waters. Without oxygen, most marine life cannot survive. [Mississippi Floods May Cause Record-Breaking Dead Zone in Gulf]

Sewage causes the majority of dead zones in Africa and South America. That's a good thing, in a way, because engineers have been working for hundreds of years on sewage management solutions. In the early 19th century, London built a sewer system to divert waste from newfangled flush toilets into the River Thames. With this influx of nutrients — one creature's sewage is another's sustenance — bacterial populations multiplied and depleted the river's oxygen. The circumstances chased off aquatic life and enveloped the city in a horrific stench, culminating in the Great Stink of 1858. Sewage treatment and managed releases remedied the situation back then, and similar infrastructure investments could likely alleviate the excrement-fueled dead zones of the modern world.

Airborne nitrogen also contributes to the world's dead zones. When cars, trucks and power plants burn fossil fuels, they emit nitrogen-laden particulates into the air. These particulates eventually settle into waterways and head for the sea. Nitrification is a special problem in Long Island Sound and the Chesapeake Bay, which have absorbed large amounts of nitrogen from coal-burning power plants in the Midwest.

Do I live near a dead zone?

The largest U.S. dead zones are in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coast of Oregon. But, everyone in the eastern and southeastern United States lives close to a dead zone of some size.

There are two reasons for the density of dead zones along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. First, look at a heat map of U.S. population density. There is an astonishing concentration of people, as well as animals and farms to feed them, in the East.

Second, there simply aren't that many rivers draining into the Pacific Ocean. With fewer rivers to carry farm runoff to the sea, fewer dead zones form.

The eastern portion of Long Island Sound has suffered dead zones nearly every year for the last two decades. Even halfway across the Sound — more than 50 miles from the most densely populated parts of New York City — the waters have been hypoxic in at least 10 of the last 20 summers.

The Chesapeake Bay hosts several dead zones, each from the drainage of a different river. According to Diaz, agricultural runoff and sewage account for about three-quarters of the problem. The other quarter is the result of airborne nitrogen.

You needn't live near a coast to have a dead zone. Lake Erie is likely in for a serious case of hypoxia this summer. The cyanobacteria that recently contaminated Toledo's drinking water will soon die and sink to the bottom, where other bacteria will feast on their remains and consume large quantities of the lake's dissolved oxygen.

Are humans solely responsible for dead zones?

No, but we almost always play a role. Natural processes, such as the churning of ocean waters, can form dead zones on their own. The massive dead zone born in 2002 near the coast of Oregon — which rivals the Gulf of Mexico dead zone in area — is the result of the upwelling of nutrients that fed an algal bloom. As the algae died and settled, they created a hypoxic area. Not all scientists think the dead zone was entirely natural, though — many believe changes in wind circulation related to global warming played a part.

Can dead zones be brought back to life?

Absolutely. The Black Sea once hosted one of the largest hypoxic zones in the world, stretching 15,000 square miles. When agricultural subsidies from the Soviet Union collapsed in the late 1980s, fertilizer runoff dropped by more than 50 percent. The waterways took three years to recover, and international support for runoff management has helped keep the Black Sea alive and well ever since.

There's no reason the United States can't adopt those practices, too — we simply need to implement the science that we already have. Agricultural researchers have made countless recommendations to minimize farm runoff, but the advice hasn't been heeded. Other property owners can help by taking it easy on the fertilizer and resisting the urge to install impermeable surfaces like concrete. And we already have plenty of other reasons to retire coal-fired power plants — dead zones are just one more. After all, it needn't take the fall of an empire to improve a nation's coastal areas.

This article is adapted from one that appeared in the NRDC publication OnEarth. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.