The worst epidemics and pandemics in history

Discover the deadliest epidemics and pandemics in history — including ones that have wiped out entire civilizations.

- Prehistoric epidemic

- Plague of Athens

- Antonine Plague

- Plague of Cyprian

- Plague of Justinian

- The Black Death

- Cocoliztli epidemic

- American Plagues

- Great Plague of London

- Great Plague of Marseille

- Russian plague

- Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic

- Flu pandemic

- American polio epidemic

- Spanish Flu

- Asian Flu

- AIDS pandemic and epidemic

- H1N1 Swine Flu pandemic

- West African Ebola epidemic

- Zika Virus

- COVID-19

- Additional resources

Some of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history have doomed whole civilizations and brought once powerful nations to their knees, killing millions. While these terrible disease outbreaks still threaten humanity, thanks to the advances in epidemiology we no longer face the same dire consequences as our ancestors once did.

Here are 21 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history, dating from prehistoric to modern times.

Related: Spanish Flu: The deadliest pandemic in history

1. Prehistoric epidemic: Circa 3000 B.C.

About 5,000 years ago, an epidemic wiped out a prehistoric village in China. The bodies of the dead were piled inside a house that was later burned down. No age group was spared, as the skeletons of juveniles, young adults and middle-age people were found inside the house.

The archaeological site is now called "Hamin Mangha" and is one of the best-preserved prehistoric sites in northeastern China. Archaeological and anthropological study indicates that the epidemic happened quickly enough that there was no time for proper burials, and the site was not inhabited again.

Before the discovery of Hamin Mangha, another prehistoric mass burial that dates to roughly the same time period was found at a site called Miaozigou, in northeastern China. Together, these discoveries suggest that an epidemic ravaged the entire region.

2. Plague of Athens: 430 B.C.

Around 430 B.C., not long after a war between Athens and Sparta began, an epidemic ravaged the people of Athens and lasted for five years. Some estimates put the death toll as high as 100,000 people. The Greek historian Thucydides (460-400 B.C.) wrote that "people in good health were all of a sudden attacked by violent heats in the head, and redness and inflammation in the eyes, the inward parts, such as the throat or tongue, becoming bloody and emitting an unnatural and fetid breath" (translation by Richard Crawley from the book "The History of the Peloponnesian War," London Dent, 1914).

What exactly this epidemic was has long been a source of debate among scientists; a number of diseases have been put forward as possibilities, including typhoid fever and Ebola. Many scholars believe that overcrowding caused by the war exacerbated the epidemic. Sparta's army was stronger, forcing the Athenians to take refuge behind a series of fortifications called the "long walls" that protected their city. Despite the epidemic, the war continued on, not ending until 404 B.C., when Athens was forced to capitulate to Sparta.

3. Antonine Plague: A.D. 165-180

When soldiers returned to the Roman Empire from campaigning, they brought back more than the spoils of victory. The Antonine Plague, which may have been smallpox, laid waste to the army and may have killed over 5 million people in the Roman empire, wrote April Pudsey, a senior lecturer in Roman History at Manchester Metropolitan University, in a paper published in the book "Disability in Antiquity," Routledge, 2017).

Related: Plague doctors: Separating medical myths from facts

Many historians believe that the epidemic was first brought into the Roman Empire by soldiers returning home after a war against Parthia. The epidemic contributed to the end of the Pax Romana (the Roman Peace), a period from 27 B.C. to A.D. 180, when Rome was at the height of its power. After A.D. 180, instability grew throughout the Roman Empire, as it experienced more civil wars and invasions by "barbarian" groups. Christianity became increasingly popular in the time after the plague occurred.

4. Plague of Cyprian: A.D. 250-271

Named after St. Cyprian, a bishop of Carthage (a city in Tunisia) who described the epidemic as signaling the end of the world, the Plague of Cyprian is estimated to have killed 5,000 people a day in Rome alone. In 2014, archaeologists in Luxor found what appears to be a mass burial site of plague victims. Their bodies were covered with a thick layer of lime (historically used as a disinfectant). Archaeologists found three kilns used to manufacture lime and the remains of plague victims burned in a giant bonfire.

Experts aren't sure what disease caused the epidemic. "The bowels, relaxed into a constant flux, discharge the bodily strength [and] a fire originated in the marrow ferments into wounds of the fauces (an area of the mouth)," Cyprian wrote in Latin in a work called "De mortalitate" (translation by Philip Schaff from the book "Fathers of the Third Century: Hippolytus, Cyprian, Caius, Novatian, Appendix," Christian Classics Ethereal Library, 1885).

5. Plague of Justinian: A.D. 541-542

The Byzantine Empire was ravaged by the bubonic plague, which marked the start of its decline. The plague reoccurred periodically afterward. Some estimates suggest that up to 10% of the world's population died.

The plague is named after the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (reigned A.D. 527-565). Under his reign, the Byzantine Empire reached its greatest extent, controlling territory that stretched from the Middle East to Western Europe. Justinian constructed a great cathedral known as Hagia Sophia ("Holy Wisdom") in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the empire's capital. Justinian also got sick with the plague but survived. However, his empire gradually lost territory in the time after the plague struck.

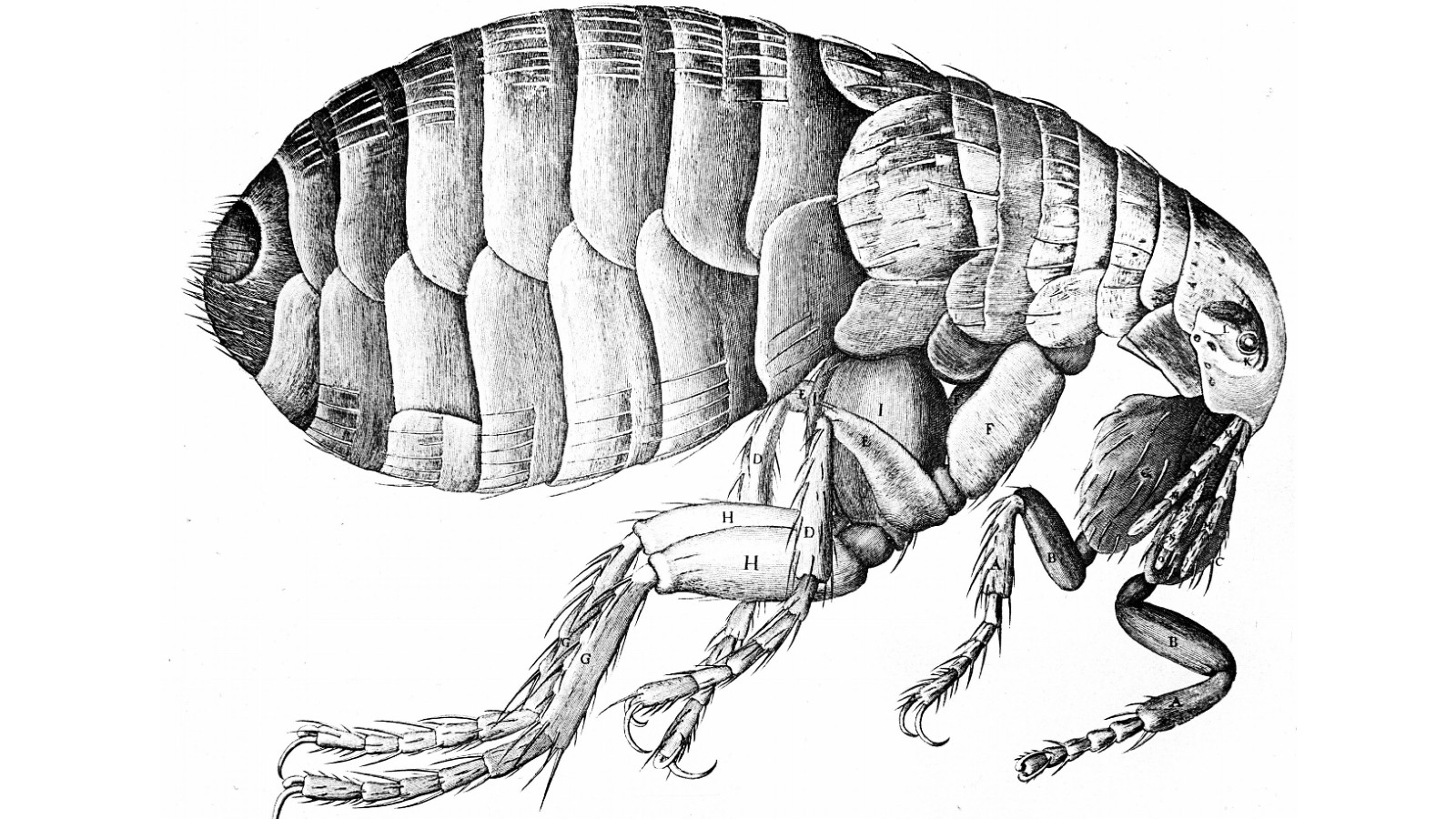

6. The Black Death: 1346-1353

The Black Death traveled from Asia to Europe, leaving devastation in its wake. Some estimates suggest that it wiped out over half of Europe's population. It was caused by a strain of the bacterium Yersinia pestis that is likely extinct today and was spread by fleas on infected rodents. The bodies of victims were buried in mass graves.

The plague changed the course of Europe's history. With so many dead, labor became harder to find, bringing about better pay for workers and the end of Europe's system of serfdom. Studies suggest that surviving workers had better access to meat and higher-quality bread. The lack of cheap labor may also have contributed to technological innovation.

7. Cocoliztli epidemic: 1545-1548

The infection that caused the cocoliztli epidemic was a form of viral hemorrhagic fever that killed 15 million inhabitants of Mexico and Central America. Among a population already weakened by extreme drought, the disease proved to be utterly catastrophic. "Cocoliztli" is the Aztec word for "pest."

A recent study that examined DNA from the skeletons of victims found that they were infected with a subspecies of Salmonella known as S. paratyphi C, which causes enteric fever, a category of fever that includes typhoid. Enteric fever can cause high fever, dehydration and gastrointestinal problems and is still a major health threat today.

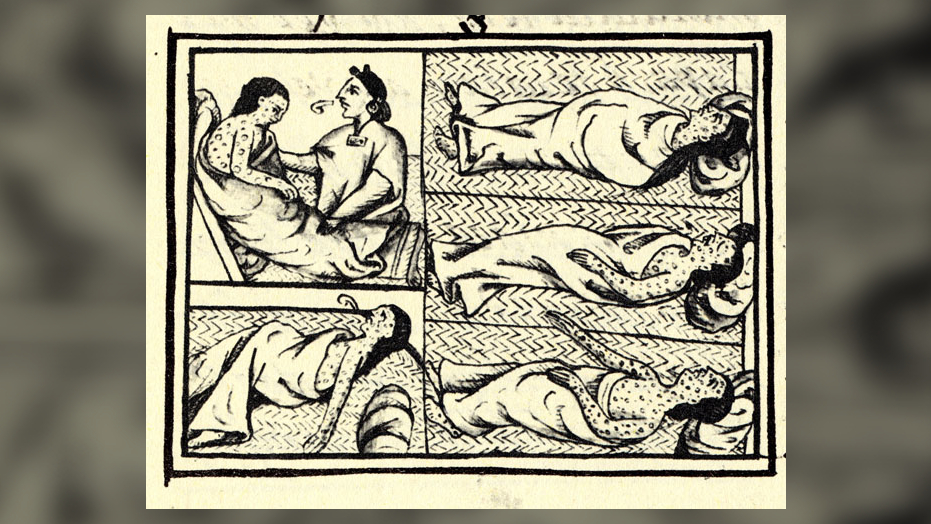

8. American Plagues: 16th century

The American Plagues were a cluster of Eurasian diseases brought to the Americas by European explorers. These illnesses, including smallpox, contributed to the collapse of the Inca and Aztec civilizations. Some estimates suggest that 90% of the indigenous population in the Western Hemisphere was killed off.

The diseases helped a Spanish force, led by Hernán Cortés, to conquer the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519. Another Spanish force led by Francisco Pizarro conquered the Incas in 1532. The Spanish took over the territories of both empires. In both cases, the Aztec and Incan armies had been ravaged by disease and were unable to withstand the Spanish forces.

When people from Britain, France, Portugal and the Netherlands began exploring, conquering and settling the Western Hemisphere, they were helped by the fact that disease had vastly reduced the size of any indigenous groups that opposed them.

9. Great Plague of London: 1665-1666

The Black Death's last major outbreak in Great Britain caused a mass exodus from London, led by King Charles II. The plague started in April 1665 and spread rapidly through the hot summer months. Fleas from plague-infected rodents were one of the main causes of transmission.

By the time the plague ended, about 100,000 people, including 15% of the population of London, had died. However, this was not the end of that city's suffering. On Sept. 2, 1666, the Great Fire of London started, lasting for four days and burning down a large portion of the city.

10. Great Plague of Marseille: 1720-1723

Historical records say that the Great Plague of Marseille started when a ship called "Grand-Saint-Antoine" docked in Marseille, France, carrying a cargo of goods from the eastern Mediterranean. Although the ship was quarantined, plague still got into the city, likely through fleas on plague-infected rodents.

Plague spread quickly and, over the next three years, as many as 100,000 people may have died in Marseille and surrounding areas. It's estimated that up to 30% of the population of Marseille may have perished.

11. Russian plague: 1770-1772

In plague-ravaged Moscow, the terror of quarantined citizens erupted into violence. Riots spread through the city and culminated in the murder of Archbishop Ambrosius, who was encouraging crowds not to gather for worship.

The empress of Russia, Catherine II (also called Catherine the Great), was so desperate to contain the plague and restore public order that she issued a hasty decree ordering that all factories be moved from Moscow. By the time the plague ended, as many as 100,000 people may have died. Even after the plague ended, Catherine struggled to restore order. In 1773, Yemelyan Pugachev, a man who claimed to be Peter III (Catherine's executed husband), led an insurrection that resulted in the deaths of thousands more.

12. Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic: 1793

When yellow fever seized Philadelphia, the United States' capital at the time, officials wrongly believed that slaves were immune. As a result, abolitionists called for people of African origin to be recruited to nurse the sick.

The disease is carried and transmitted by mosquitoes, which experienced a population boom during the particularly hot and humid summer weather in Philadelphia that year. It wasn't until winter arrived — and the mosquitoes died out — that the epidemic finally stopped. By then, more than 5,000 people had died.

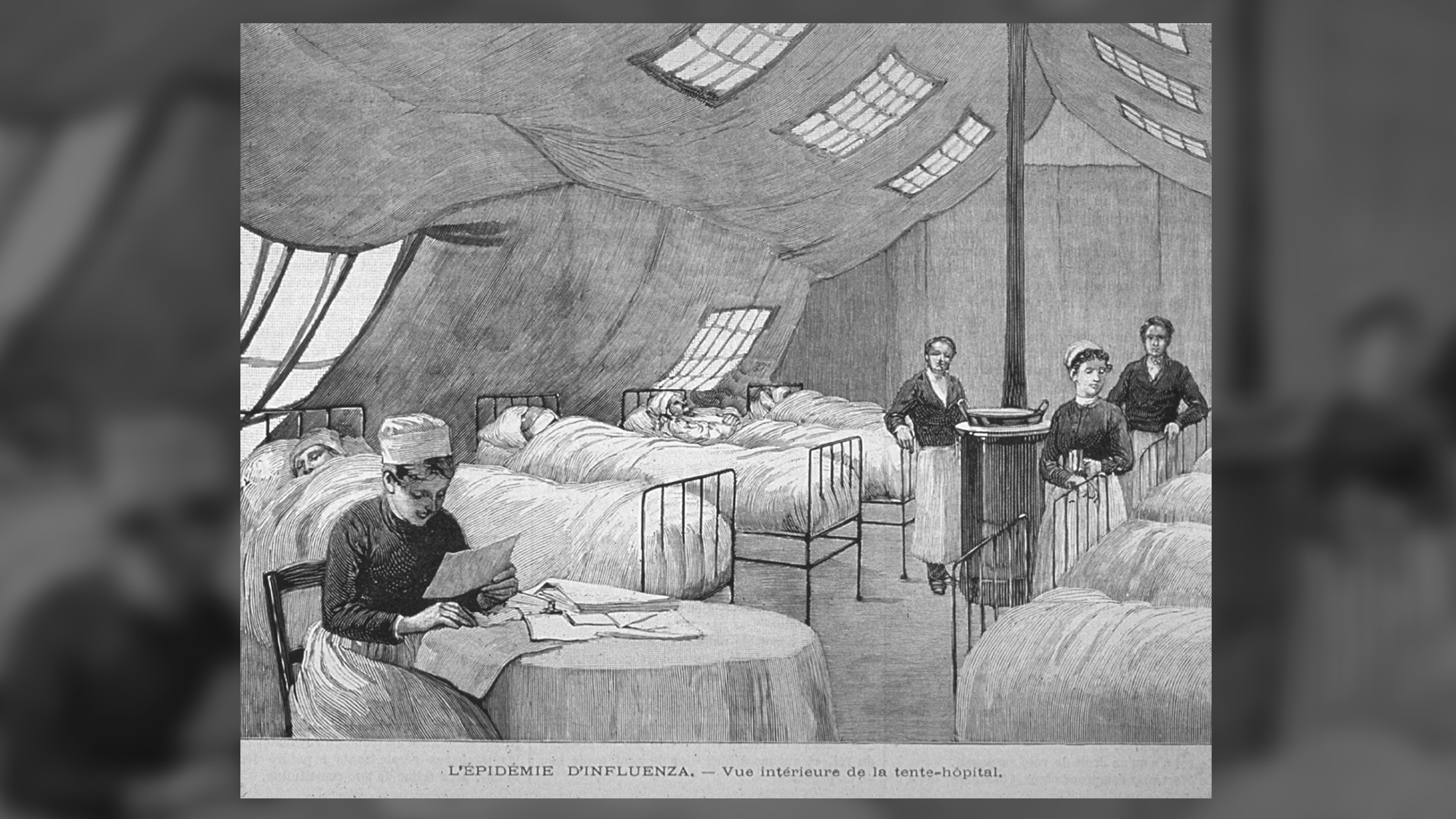

13. Flu pandemic: 1889-1890

In the modern industrial age, new transport links made it easier for influenza viruses to wreak havoc. In just a few months, the disease spanned the globe, killing 1 million people. It took just five weeks for the epidemic to reach peak mortality.

The earliest cases were reported in Russia. The virus spread rapidly throughout St. Petersburg before it quickly made its way throughout Europe and the rest of the world, despite the fact that air travel didn't exist yet.

14. American polio epidemic: 1916

A polio epidemic that started in New York City caused 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths in the United States. The disease mainly affects children and sometimes leaves survivors with permanent disabilities.

Polio epidemics occurred sporadically in the United States until the Salk vaccine was developed in 1954. As the vaccine became widely available, cases in the United States declined. The last polio case in the United States was reported in 1979. Worldwide vaccination efforts have greatly reduced the disease, although it is not yet completely eradicated.

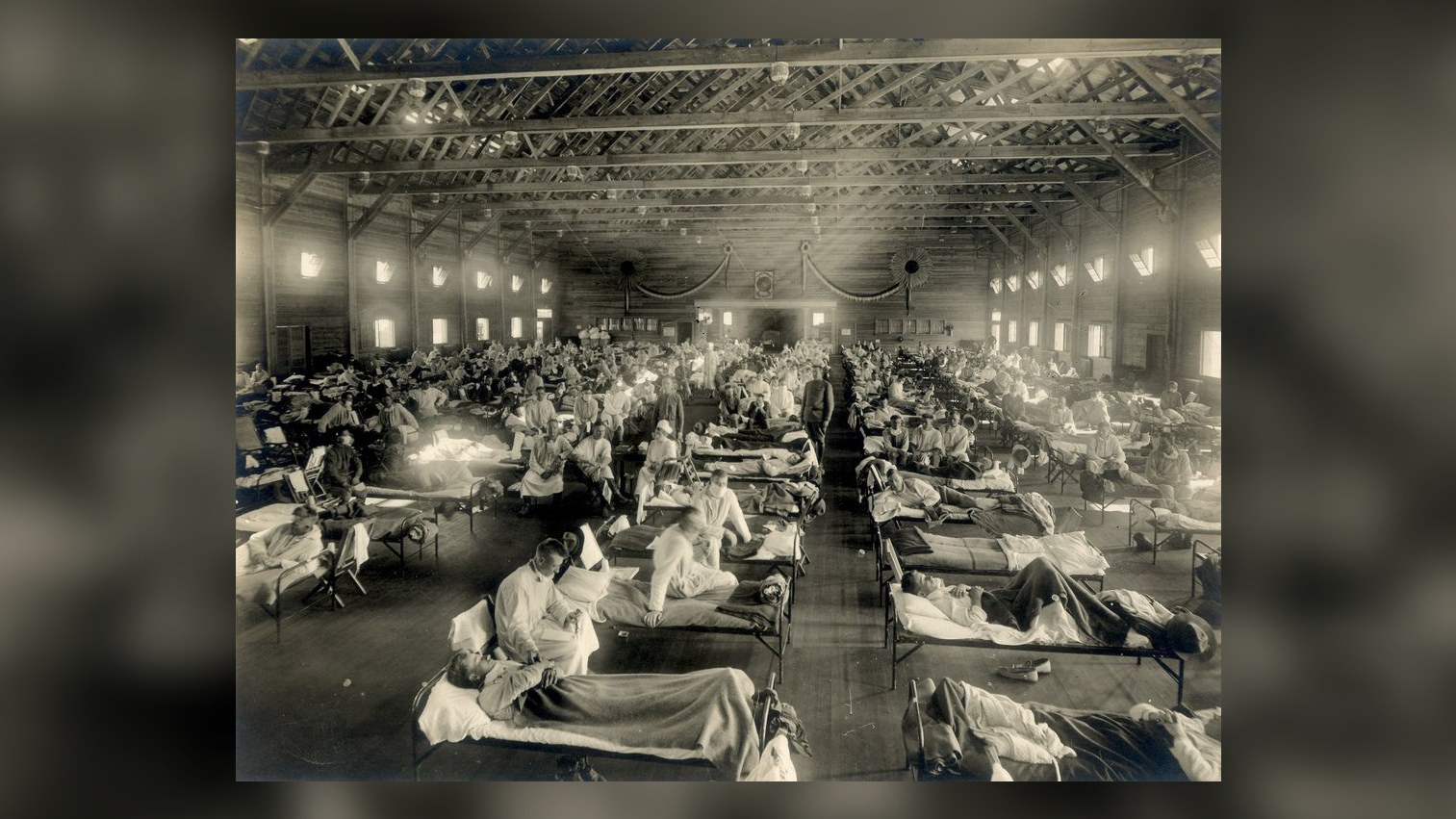

15. Spanish Flu: 1918-1920

An estimated 500 million people from the South Seas to the North Pole fell victim to Spanish Flu. One-fifth of those died, with some indigenous communities pushed to the brink of extinction. The flu's spread and lethality was enhanced by the cramped conditions of soldiers and poor wartime nutrition that many people were experiencing during World War I.

Despite the name Spanish Flu, the disease likely did not start in Spain. Spain was a neutral nation during the war and did not enforce strict censorship of its press, which could therefore freely publish early accounts of the illness. As a result, people falsely believed the illness was specific to Spain, and the name Spanish Flu stuck.

16. Asian Flu: 1957-1958

The Asian Flu pandemic was another global showing for influenza. With its roots in China, the disease claimed more than 1 million lives. The virus that caused the pandemic was a blend of avian flu viruses.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that the disease spread rapidly and was reported in Singapore in February 1957, Hong Kong in April 1957, and the coastal cities of the United States in the summer of 1957. The total death toll was more than 1.1 million worldwide, with 116,000 deaths occurring in the United States.

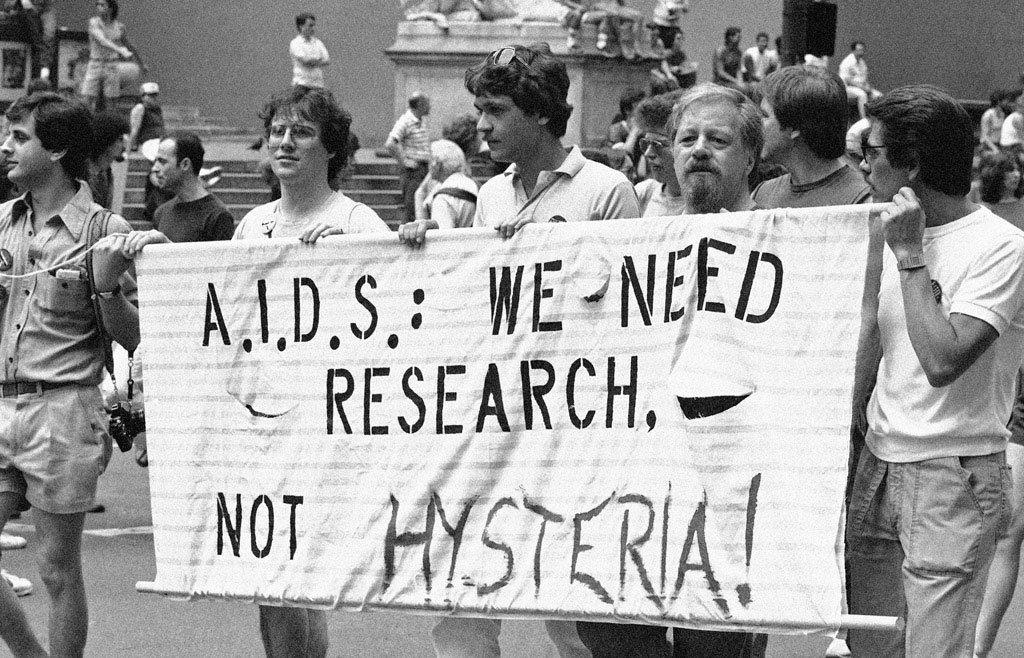

17. AIDS pandemic and epidemic: 1981-present day

AIDS has claimed an estimated 35 million lives since it was first identified. HIV, which is the virus that causes AIDS, likely developed from a chimpanzee virus that transferred to humans in West Africa in the 1920s. The virus made its way around the world, and AIDS was a pandemic by the late 20th century. Now, about 64% of the estimated 40 million living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) live in sub-Saharan Africa.

For decades, the disease had no known cure, but medication developed in the 1990s now allows people with the disease to experience a normal life span with regular treatment. Even more encouraging, two people have been cured of HIV as of early 2020.

18. H1N1 Swine Flu pandemic: 2009-2010

The 2009 swine flu pandemic was caused by a new strain of H1N1 that originated in Mexico in the spring of 2009 before spreading to the rest of the world. In one year, the virus infected as many as 1.4 billion people across the globe and killed between 151,700 and 575,400 people, according to the CDC.

The 2009 flu pandemic primarily affected children and young adults, and 80% of the deaths were in people younger than 65, the CDC reported. That was unusual, considering that most strains of flu viruses, including those that cause seasonal flu, cause the highest percentage of deaths in people ages 65 and older.

But in the case of the swine flu, older people seemed to have already built up enough immunity to the group of viruses that H1N1 belongs to, so weren't affected as much. A vaccine for the H1N1 virus that caused the swine flu is now included in the annual flu vaccine.

Related: How does the COVID-19 pandemic compare to the last pandemic?

19. West African Ebola epidemic: 2014-2016

Ebola ravaged West Africa between 2014 and 2016, with 28,600 reported cases and 11,325 deaths. The first case to be reported was in Guinea in December 2013, then the disease quickly spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone. The bulk of the cases and deaths occurred in those three countries. A smaller number of cases occurred in Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, the United States and Europe, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

There is no cure for Ebola, although efforts at finding a vaccine are ongoing. The first known cases of Ebola occurred in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976, and the virus may have originated in bats.

20. Zika Virus epidemic: 2015-present day

The impact of the recent Zika epidemic in South America and Central America won't be known for several years. In the meantime, scientists face a race against time to bring the virus under control. The Zika virus is usually spread through mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, although it can also be sexually transmitted in humans.

While Zika is usually not harmful to adults or children, it can attack infants who are still in the womb and cause birth defects. The type of mosquitoes that carry Zika flourish best in warm, humid climates, making South America, Central America and parts of the southern United States prime areas for the virus to flourish.

21. COVID-19 pandemic: 2019-present day

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, driven by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, may be the world's deadliest viral outbreak in more than a century. From the virus' initial detection in December 2019 to mid-December 2020, the pathogen infected at least 75 million people and caused 1.6 million deaths, Live Science previously reported. As of Sept. 2021, COVID-19 had killed more people in the U.S. than the so-called Spanish flu did during the 1918 flu pandemic.

That said, in total, the 1918 pandemic claimed more than 50 million lives worldwide, out of a global population of roughly 1.8 billion people; the death toll was high, in part, because no vaccines were available at the time and doctors lacked antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections. By comparison, today's global population is nearly 8 billion, and as of mid-August 2022, about 6.4 million people had died of COVID-19, although the reported number of confirmed deaths is likely lower than the true total.

To see the updated global case count and number of confirmed deaths from COVID-19, visit the WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.

Additional resources

Learn what a pandemic is with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Discover what the coronavirus outbreak can teach us about bringing samples back from Mars. And Learn about how the spread of COVID-19 is fueled through stealth transmission.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.