Arctic Ice Returns, Thin and Tentative

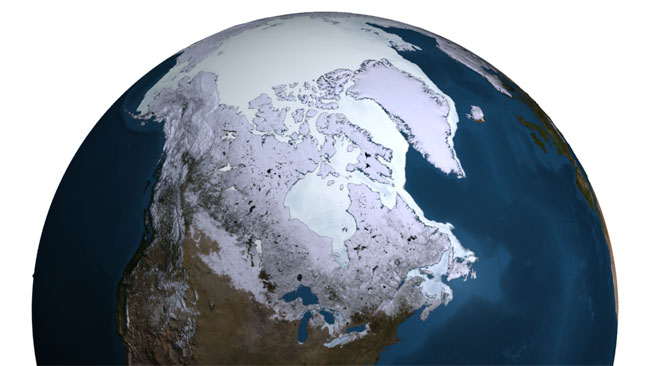

Arctic ice has reformed rapidly this winter after a record summer low, but it still covers less of the Arctic Ocean than it did in previous decades, NASA scientists announced today in an update of the states of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice.

March is the month where Arctic sea ice traditionally hits its highest extent after the Northern Hemisphere winter and Antarctic sea ice reaches its lowest extent. NASA satellites have monitored sea ice coverage over both poles for nearly 40 years.

Arctic sea ice reached a record low this past summer, with 23 percent less sea ice cover than the previous record low and 39 percent less than the average amount that has previously spanned the Arctic Ocean in the summer months.

This extraordinarily high melt opened the fabled Northwest Passage and spurred scientists' worries about whether the Arctic ice had reached a tipping point, where melting begins to spiral out of control.

NASA's satellite observations showed that while this winter's ice extent didn't dip below previous records, it was still well below the average amount seen in the past.

Antarctic sea ice has largely remained stable over the years of NASA's observations. The Antarctic has little long-term sea ice and a different climate and weather regime than the Arctic.

Ice ages

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The area of ocean covered by sea ice isn't the only factor in the "health" of the Arctic ice.

Arctic sea ice comes in two types: older, thicker perennial ice that has survived at least one summer melt season and younger, thinner seasonal ice that forms in the winter and melts again in the summer.

Seasonal ice melts more easily because it is thin and salty, and so "it's flexible and crushable and more susceptible to winds and currents," said Seelye Martin of NASA's Cryospheric Sciences Program.

Colder temperatures in parts of the Arctic increased the amount of thin, seasonal ice that formed this winter. So while Arctic sea ice was dominated by multiyear, perennial ice in past decades , it is mostly now younger, newly-formed ice.

The amount of older, perennial sea ice has substantially decreased over the past few years, and "has reached an all-time minimum," Martin said. This low is in part due to the substantial 2007 summer melt, attributed in part to climate change.

Future of the Arctic

What these colder temperatures and the slightly higher winter extent this year will mean come summer is uncertain. But because the majority of the ice is young and thin, it would be more susceptible to summer melt.

Whether any perennial sea ice will recover is also uncertain, but "it's not likely that the perennial ice cover will recover [to where it was in the past] in the near future," said Josefino Comiso of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Some of the seasonal ice could become perennial sea ice if summer conditions are cooler than normal this year, Meier noted, as some of the seasonal ice has formed higher north than ever before.

But, "one cold summer is not going to do it, one cold winter is not going to do it," Meier said. Numerous years of colder temperatures would be needed to restore the Arctic sea ice to where it was in the 1980s, and that is not likely to happen with the increasing levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, he added.

- North vs. South Poles: 10 Wild Differences

- Multiple Studies Reveal Dire Meltdown in Arctic

- Timeline: The Frightening Future of Earth

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.