Why the China Quake Was So Devastating

The 7.9-magnitude earthquake that hit China's Sichuan province, leveling buildings and taking tens of thousands of lives, might not have wrought such destruction in the United States, experts say.

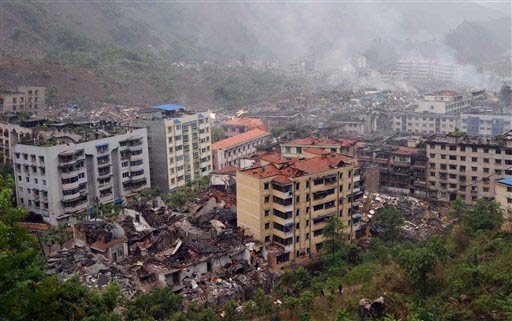

Ground-shaking from the relatively shallow earthquake in China leveled entire villages, burying thousands of people beneath the rubble of collapsed buildings, including 4 million homes reportedly shattered. The death toll exceeds 15,000 and could rise to 50,000.

Due to its intensity and relatively shallow origin — just 11.8 miles (19 km) below the surface — the China earthquake generated extremely powerful shaking felt as far away as Taiwan. Earthquake engineers speculate the adobe and masonry buildings and homes, many of which were probably not reinforced with steel as building codes dictate, added to the earthquake damage, especially in more rural areas.

LiveScience reported that an earthquake somewhat like China's on one of the faults in the Los Angeles area would be a "worst-case scenario," leading to extensive damage. Though extensive, engineers say the devastation would be much less than what occurred in China, due in part to better enforcement of building codes here. Yet they speculate that some buildings in the United States, such as warehouse-like structures and some Wal-Marts and Targets, may not be equipped to withstand intense ground-shaking.

West Coast cities have been vigilant about ensuring that buildings meet earthquake-safety codes, including retrofitting old homes and businesses. But in other parts of the country, where earthquakes can be powerful but rare, many buildings may not be prepared to hold up to powerful shaking, the engineers said.

Shake-proof buildings

Experts can't predict with any certainty the level of damage that would occur if a China-like earthquake were to hit the United States. However, they can make some speculations, based on the magnitude and ground-shaking.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"You certainly wouldn't see the extent of damage you see here [in China]," said Reginald DesRoches, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Georgia Tech. "I'm pretty confident about that. You just wouldn't see the level of damage, because they do really enforce the regulations, particularly in California."

DesRoches said building codes in the United States and China dictate the minimum level of safety for constructed buildings with regard to natural disasters like earthquakes. The main factor that causes structures to collapse, and therefore they must be braced against it, is ground-shaking.

In one approach to doing this, engineers add steel to concrete or bricks. The steel makes a brittle structure that would easily snap if rattled into a ductile one that can effectively wave with the temblor's motion.

"By adding steel to a structure that may be made of brick, you make the entire thing much more ductile," DesRoches told LiveScience. "That's how things should be built, and in fact the Chinese code specifies that. But the builders, to save money, just put the brick and didn't add the appropriate amount of steel, if any at all."

In parts of California near the San Andreas Fault, DesRoches says, modern structures are designed to withstand ground-shaking levels comparable to those felt in the Sichuan province. Over the past two decades or so, he says, older buildings in California have been rehabilitated to meet current safety standards.

"China didn't get an adequate seismic design code until following the big earthquake they had in 1976," DesRoches said. "If the buildings were older and built prior to that [1976 earthquake], chances are they weren't built for adequate earthquake forces."

Particularly the poorer, rural villages in China were hardest hit this week, according to news reports, highlighting a gap in building-code oversight that's related to economics.

"The earthquake occurred in the rural part of China," said Swaminathan Krishnan, assistant professor of civil engineering and geophysics at Caltech. "Presumably, many of the buildings were just built; they were not designed, so to speak."

Krishnan added, "There are very strong building codes in China, which take care of earthquake issues and seismic design issues. But many of these buildings presumably were quite old and probably were not built with any regulations overseeing them."

Seismic structures

In 2007, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) updated its seismic hazard map, which pinpoints areas vulnerable to earthquakes and the amount of ground-shaking that could occur. The maps also set building codes corresponding to the potential level of shaking.

Even so, earthquake engineers and seismologists are concerned about certain types of structures that could be vulnerable to major earthquakes.

Brick buildings without steel reinforcements would be considered the most vulnerable to collapse during ground-shaking, Krishnan said. "Now we can confidently say there are no un-reinforced masonry buildings in southern California."

However, some warehouses and other structures made out of concrete with little steel for flexing could collapse in a quake like the one that hit China.

"The next most risky buildings are these non-ductile concrete buildings. I hate to say it's similar to the Chinese situation, but it could be; we don't know exactly how bad these buildings are," Krishnan said. And so "the kind of collapses you saw in China, we might see here."

Wal-Marts and Targets could also take a hit, Krishnan said. Many of these mega buildings are constructed in a so-called tilt-up fashion in which huge concrete walls are constructed horizontally on the ground and then tiled up vertically and braced to the roof with some kind of connections.

"The connections are the weak link," Krishnan said. "When these connections between the roof and these wall panels go, you are going to see pretty big collapses."

Seismic cities

Some cities are more shake-resistant than others.

"The cities that have experienced earthquakes like Seattle and places in California are clearly much more vigilant, so those are probably some of the safest cities," DesRoches said.

But Memphis and St. Louis, which are in the New Madrid seismic zone, are worrisome to DesRoches and other experts.

"They haven't had an earthquake in a couple hundred years, so those are areas that people are concerned about, just because they don't have the history of doing seismic design as you do in California," DesRoches said. "Now new structures are built the right way, but older structures haven't been designed appropriately [in Memphis and St. Louis]."

He adds Charleston, South Carolina to the "hazardous city" list.

"Charleston is another city that is somewhat hazardous, because they do have a history of earthquakes, but they're very infrequent. The last [big] one was in 1886," DesRoches said.

- Video: Earthquake Forecast

- The Worst Natural Disasters Ever

- Image Gallery: Deadly Earthquakes

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.