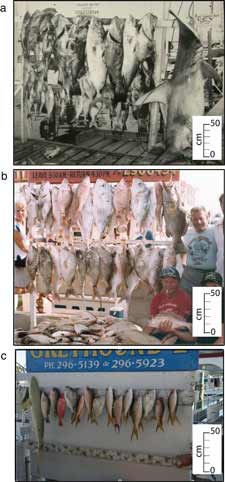

Old Photos Document Dramatic Decline in Trophy Fish Size

Archival photographs spanning more than five decades reveal a drastic decline of so-called "trophy fish" caught around coral reefs surrounding Key West, Florida.

Loren McClenachan, a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, estimates that large predatory fish have declined in weight by 88 percent in modern photos compared to black-and-white shots from the 1950s. The average length of sharks declined by more than 50 percent in 50 years, the photographs revealed.

The study mirrors others that reveal stark changes to animal sizes caused by hunting or fishing, in which the largest of a species are often sought as trophy specimens.

McClenachan's findings will be published in the journal Conservation Biology. In a companion paper being published in the Endangered Species Research journal, McClenachan used similar methods to document the decline of the globally endangered goliath grouper fish.

"These results provide evidence of major changes over the last half century and a window into an earlier, less disturbed fish community," McClenachan writes.

While conducting research for her doctoral thesis on coral reef ecosystems of the Florida Keys, McClenachan found what she describes as a gold mine of photographic data at the Monroe County Library in Key West. Hundreds of archived photographs, snapped by professional photographer Charles Anderson and others, depict sport fishing passengers posing next to a hanging board used to determine the largest catches of the day. All of the photographs document sport fishing trips targeting coral reef fishes around the Florida Keys. McClenachan supplemented the study with her own photographs and observations on sport fishing trips in 2007.

In all, she measured and analyzed some 1,275 fish from pictures.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"While the photographs in this study do not provide a direct measurement," McClenachan admits, "they clearly demonstrate that large fish were more abundant in the past."

She said changes due to fishing pressures had likely begun before the 1950s, and she said scientists must be careful when creating baselines for a study.

"Managers mistakenly assume that what they saw in the 1980s was pristine, but most prized fish species had been reduced to a small fraction of their pristine abundance long before. Historical ecology provides the critical missing data to evaluate what we lost before modern scientific surveys began."

"I think the photos in this very original paper will make lots of people change their mind," said Daniel Pauly, a professor at the University of British Columbia Fisheries Center and Zoology Department.