Earth Checkup: 10 Health Status Signs

Planetary Vital Signs

LiveScience takes a look at the state of Earth's systems and inhabitants — a planetary checkup to see what things are going right and which areas could use some improvement. From both poles to the depths of the sea, from the air we breathe to the air that keeps us from burning up, we're understanding more and more about our impact on the planet and ourselves.

Where we fit in

While we humans are the significant force behind much of the changes to Earth's systems, those effects can come back and impact us through our health and changing environmental conditions that we must adapt to. The impact we have and its effect on us will be magnified as human populations continue to grow. In 2007, the world population passed the six billion mark. That year also marked the first time in human history that more people were living in urban settings than rural areas. All six billion of us must compete for a limited number of resources, including water, food, and fuel. Some scientists say that we have already reached the limits of what our planet can support and that we need to curb population growth for the health of our species and the planet.

Animals in peril

When habitats are changed and threatened, the animals that dwell in them also come under pressure. The 2008 Red List of endangered species issued by the World Conservation Union identified almost 45,000 endangered species, with 1 in 4 mammals being threatened with extinction. Tigers, elephants, and several species of primates are known victims of habitat change — and poaching — in Africa and Asia. Frog populations all over the globe have been decimated by the spread of a deadly fungus. In the oceans, sharks, whales, dolphins and some species of fish are also hurting. The news isn't all bad, as many bird populations are recovering thanks to the ban on DDT, and polar bears were placed on the Endangered Species List last year. Though on the other end of the Earth, new studies have found that penguins are also in peril due to a combination of changes in climate, overfishing and pollution. Also, the Bush Administration revised the Endangered Species listing rules, a move criticized some conservationists.

Atmospheric buildup

Last week, the E.P.A. declared that carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases are pollutants under the Clean Air Act, paving the way for regulations of emissions. Some companies and nations have already pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but many of these goals have not been met. That and the rapid pace of development in countries like China and India have kept levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases rising globally, and at a faster rate than in previous years. China leads all nations in total emissions, but the United States is still number one in emissions per capita. Many proposals for cap-and-trade systems, methods for trapping carbon dioxide emissions underground and alternative forms of energy have been put forward, but it's up to governments and other groups to pick and choose among them.

Water stress

It's essential to life as we know it, and though the planet's surface is two-thirds water, pollution is making it unsuitable for the humans that drink it and the animals that live in it. The effects of global warming are also altering the patterns of water availability for drinking and agriculture: already arid regions will likely get drier, and rising sea levels could force salty sea water into normally freshwater aquifers. Some scientists say western U.S. water supplies are already being impacted by climate change and that policy advisors need to set better management practices. Depending on where they are grown, the crops used to make biofuels could stress local water supplies.

Deforestation

On land, the actual rainforests aren't fairing much better, thanks in large part to deforestation. Forested areas, particularly rainforests, are key areas of biodiversity; they also absorb carbon dioxide and produce oxygen. Globally the rate of deforestation is about 32 million acres a year.Large swaths of the Brazilian Amazon have been chopped down to make room for crops and cattle, and the rate of clearance seems to be speeding up. The Brazilian government has made strides in protecting forests, but the problem still persists. Asia and Africa have also seen rising rates of deforestation. Drought caused by global warming could exacerbate the situation in some areas. Forests in the United States and Europe are fairing better, as reforestation has occurred in the last decade.

Corals in crisis

Coral reefs, sometimes called the "rainforests of the ocean" are critical marine habitats. But reefs from the Caribbean to the Great Barrier Reef have been under pressure in recent decades from overfishing, pollution, disease, warming waters and ocean acidification. Ocean waters become more acidic as they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere; as the acid level of the water rises, it dissolves the minerals used by coral and other animals to build their skeletons. A 2007 study found that this stressor alone could make most current coral habitats too acidic for reef growth by 2050.

Ocean dead zone expansion

For years now, so-called oceanic dead zones - pockets of the sea where oxygen is so depleted that many fish, crustacean and other species can't survive, such as in the Gulf of Mexico - have been a growing concern. These suffocating spaces are formed when fertilizer runoff pours in from rivers and promote algal blooms that eat up all the oxygen as they die and decompose. Controlling fertilizer runoff could improve the situation fairly quickly, but studies have suggested that increased crop growth for producing biofuels could send more fertilizer running downstream and that the absorption of carbon dioxide by the ocean could independently expand these unproductive zones.

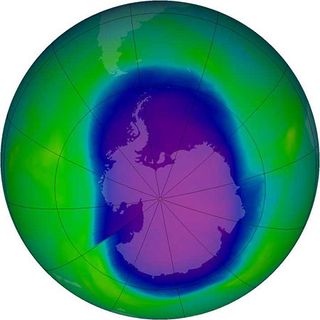

Ozone hole recovery

Discovered in 1985, the hole in the ozone layer protects Earth's denizens by absorbing harmful ultraviolet rays. Efforts to ban or reduce the chemicals that eat away at the ozone in the stratosphere have initiated the gradual recovery of the hole. This recovery will take decades though because these pollutants hang around for a long time. So far the ozone hole over Antarctica has remained about the same size, fluctuating year-to-year with changes in wind circulation patterns. While it will still take some time for the ozone hole to recover, if countries hadn't acted to ban ozone-destroying substances, the situation could have been much worse.

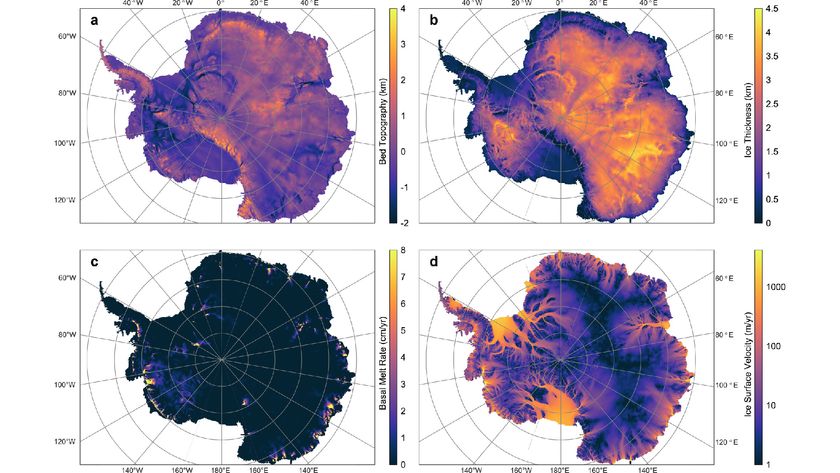

Antarctic collapses

Antarctica has seen its share of melt as well: In April, an ice bridge believed to pin the Wilkins Ice Shelf in place snapped. Wilkins is one of nine Antarctic ice shelves that have receded or collapsed in recent decades - the most dramatic collapses were those of the Larsen A and B shelves, which abruptly crumbled in 1995 and 2002, respectively. Most of the dramatic melting has occurred in the Antarctic Peninsula, the only part of the southernmost continent that juts north of the Antarctic Circle. In contrast, the interior of the frozen continent was thought to be cooling, but this year new research suggested that these vast ice sheets are also experiencing warming but the trend has so far been masked by the cooling influence of the ozone hole. Parties to the Antarctic Treaty have agreed to tourism limits to protect the continent's fragile ecosystems.

Arctic meltdown

After dramatic meltdowns in recent summers that have left Arctic ice thinner than in the past, some scientists are increasingly worried about the future survival of Arctic sea ice. One recent study estimated that Arctic waters could be ice free in the summer in a little as 30 years, much sooner than previous estimates. Such catastrophic melt could reinforce the global warming trend and further imperil Arctic residents, from humans to narwhals and polar bears, which were listed as an Endangered Species in May 2008.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.