Powerful Ideas: Bacteria Clean Sewage and Create Electricity

Editor's Note: This occasional series looks at powerful ideas — some existing, some futuristic — for fueling and electrifying modern life.

Batteries made with microbes could help generate power by cleaning up organic waste at the same time.

Sewage is loaded with energy-rich sugars that researchers have struggled for years to convert into useful power. To do so, investigators have experimented with nature's experts on breaking down waste — bacteria.

"It's kind of like the movie 'The Matrix,'" said environmental engineer Bruce Logan at Penn State University. "Instead of wiring people up to generate electricity, we are using bacteria to directly generate electricity."

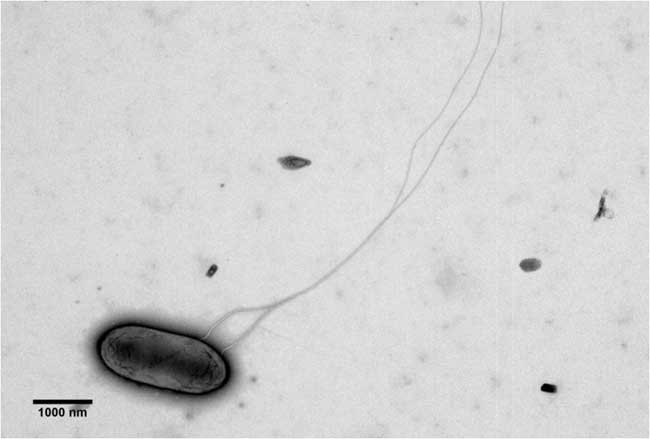

Scientists have experimented with a variety of bacteria, but one kind that environmental microbiologist Derek Lovley at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and his colleagues have focused on is Geobacter, which is naturally found in many soils and sediments.

"Geobacter grows by breaking down organic materials and transferring electrons pretty much onto anything that looks like iron," he said. "It's up in the top of the list in terms of generating high power densities."

When attacking environmental pollutants such as aromatic hydrocarbons, Geobacter can break down some 90 percent, Lovley said. All in all, systems incorporating Geobacter can recover up to nearly all the electrons within sewage.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although wastewater could essentially serve as a free source of fuel, wastewater alone cannot solve the energy crisis, Logan noted. If animal, food industry and domestic wastewaters were combined together, they could provide roughly 500 trillion BTUs of energy — an impressive figure, until compared with the roughly 100,000 trillion BTUs of energy the United States uses every year.

Still, all the energy that bacteria could generate from wastewater could help power the considerable needs of wastewater treatment. For instances, in the United States, roughly 33 billion gallons of wastewater are treated daily for an annual cost of more than $25 billion, and some 1.5 percent of the electricity produced every year goes into wastewater treatment alone.

"Hopefully, by using bacteria, we will get back more energy than that needed to treat the wastewater, so that we can also have energy to produce drinking water," Logan said.

Logan and his colleagues have worked to build microbial systems that generate more power for less money. "In 2004, if we made one of these systems, a cubic-meter reactor would probably have cost $100,000," he said. "Now it's just a few thousand dollars. We want to make this economical to use."

Aside from wastewater, another potentially vast source of energy that bacteria could exploit are the organic chemicals in ocean mud. Although humanity already taps into some of this fuel in the form of petroleum, most of this energy reservoir remains beyond reach because it is not nearly as easy to extract and use as oil.

"Organic matter keeps on raining down onto marine sediments as organisms die, so the idea is that marine sediments could basically be a perpetual system for powering electronic devices," Lovley said.

In terms of advancing these microbial systems further, Lovley has experimented with bacteria in terms of genetic engineering. "So far we've managed to double power output that way," Lovley said.

Lovley added that through breeding programs led to strains that "increased power by at least an order of magnitude." The resulting bacteria all had more hair-like filaments known as pili emerging from their surfaces than normal, suggesting that genetically engineering to produce more pili could lead to even more productive microbes.

"There are a lot more surprises to comes from these bacteria," Lovley said.