Why Pacific Hurricanes Hit the Americas So Rarely

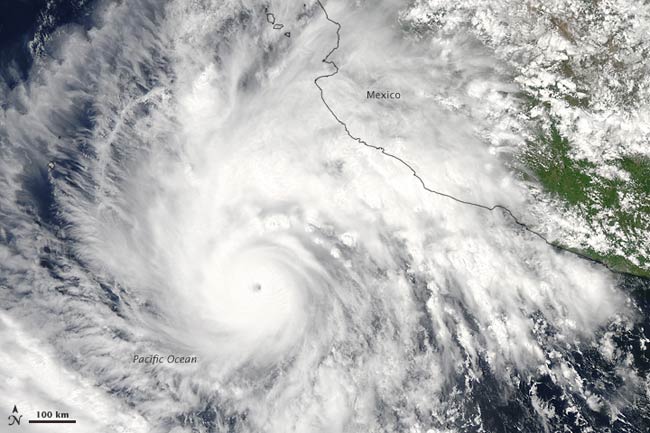

Stories of hurricane winds and rain lashing the coasts of Florida, Louisiana and other southeastern states pop up in the news constantly during the summer, but warnings of Pacific storms such as Jimena are few and far between.

In fact, only one hurricane is thought to have ever struck California, and that was clear back in 1858. Could it happen again? Not impossible, but also extremely unlikely in any given year.

The disparity is a result of the oceanic and atmospheric conditions at play in both basins, which send hurricanes in the Atlantic toward land and hurricanes in the Pacific away from it, generally sparing West Coasters from the rages of these storms.

The hurricanes that swirl over both oceans form through the same mechanism, whereby warm ocean waters fuel the rotating storms. (Typhoons are also the same phenomenon; the name is simply the designation used in the western Pacific and Indian Oceans.)

"They are identical in every way, shape and form," said Dennis Feltgen, a spokesman for the National Hurricane Center in Miami.

But Pacific hurricanes make the news less often and do less damage than their Atlantic counterparts. More hurricanes form on average in the eastern North Pacific basin than in the Atlantic (15 vs. 11, respectively), but Pacific storms almost never hit the United States, while Atlantic storms do so a little less than twice a season on average. (The Atlantic hurricane season lasts from June 1 to Nov. 30.)

The conditions guiding the development and movement of these storms impact whether, and where, they hit land.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Winds and warmth

The prevailing winds in the tropical latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, where tropical cyclones typically form, blow from east to west, so this is roughly the direction hurricanes migrate. In the Atlantic Ocean, that means storms move toward land, particularly the eastern and southern coasts of the United States, as well as the islands of the Caribbean and sometimes Mexico.

But in the Pacific, those same winds move storms away from landfall. "The vast majority of them just go out to sea," Feltgen said.

Occasionally, weather patterns will keep Atlantic storms away from land or push Pacific storms towards it, as is the case with Jimena.

Another factor that tends to protect, say, California is the comparatively frigid water temperatures of the ocean. Hurricanes feed on warm ocean waters; colder water temperatures cut off their fuel source and weaken the storms. While hurricanes are typically stifled before can reach California, hurricanes on the East Coast can venture much further north, thanks to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream.

Pacific storms

Until recently, only one storm, which fell in the less intense category of tropical storm, is known to have made landfall on the coast of California, on Sept. 25, 1939. Three other have brought tropical storm force winds to the southwestern United States, but those came up by way of Baja California.

Jimena is likely to follow such a pattern, potentially bringing some rain to Arizona after it has wrung itself out over Baja California, where it is expected to make landfall as a major hurricane, with the potential to cause significant damage.

In 2004, however, it was re-discovered that a hurricane likely struck San Diego in 1858. Michael Chenoweth, a researcher with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, found mention of the storm in California newspaper accounts from the period. Chenoweth and Chris Landsea, also of NOAA, used historical newspaper accounts and meteorological observations to characterize the forgotten hurricane and retrace its path.

Accounts from the storm mention terrific gales, roofs ripped off of houses, trees uprooted and fences pulled up.

That year may have seen strong El Nino conditions, which makes for warmer, more hurricane-friendly waters in the Pacific (while become less favorable for hurricanes in the Atlantic during an El Nino year).

This finding is important when considering that global warming is likely to raise ocean surface temperatures. If a Category 1 hurricane (the weakest hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale of hurricane strength) were to hit San Diego or Los Angeles today, it could cause several hundred million dollars in damage.

Occasionally hurricanes will jump basins: For example, Hurricane Cesar became Northeast Pacific Hurricane Douglas in July 1996.

- Quiz: Test Your Hurricane Smarts

- Hurricane News, Images and Information

- Hurricanes: Our 5 Worst Fears

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.