The Most Surprising Results of Global Warming

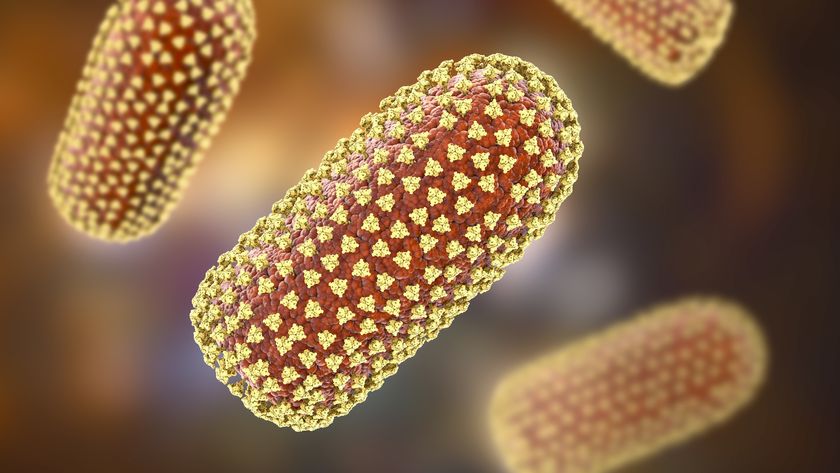

At the United Nations meeting on climate change next week, scientists will be discussing some of the potentially devastating effects of global warming, such as rising temperatures, melting ice caps and rising sea levels in the near future. But Earth's changing climate is already wreaking havoc in some very weird ways. So gird yourself for such strange effects as savage wildfires, disappearing lakes, freak allergies, and the threat of long-gone diseases re-emerging.

10. Aggravated Allergies

Have those sneeze attacks and itchy eyes that plague you every spring been worsening in recent years? If so, global warming may be partly to blame. Over the past few decades, more and more Americans have started suffering from seasonal allergies and asthma. Though lifestyle changes and pollution ultimately leave people more vulnerable to the airborne allergens they breathe in, research has shown that the higher carbon dioxide levels and warmer temperatures associated with global warming are also playing a role by prodding plants to bloom earlier and produce more pollen. With more allergens produced earlier, allergy season can last longer.

9. Pulling the Plug

A whopping 125 lakes in the Arctic have disappeared in the past few decades, backing up the idea that global warming is working fiendishly fast near Earth's poles. Research into the whereabouts of the missing water points to the probability that permafrost underneath the lakes thawed out. When this normally permanently frozen ground thaws, the water in the lakes can seep through the soil, draining the lake. One researcher likened it to pulling the plug out of a bathtub. When the lakes disappear, the ecosystems and organisms they support also lose their home

8. Arctic in Bloom

While melting in the Arctic might cause problems for plants and animals at lower latitudes, it's creating a downright sunny situation for Arctic biota. Arctic plants usually remain trapped in ice for most of the year. Nowadays, when the ice melts earlier in the spring, the plants seem to be eager to start growing. Research has found higher levels of the photosynthesis product chlorophyll in modern soils than in ancient soils, showing a biological boom in the Arctic in recent decades. 7. Thicker Skins

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

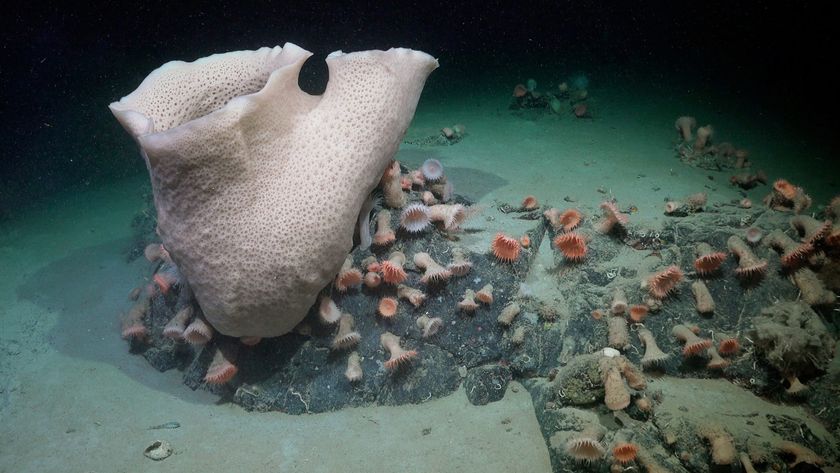

One worry connected to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels is the accompanying increase of carbon dioxide in the ocean, as ocean waters dissolve the gas from the air. Rising levels of carbon dioxide make ocean water more acidic, which can make it harder for some shelled sea dwellers to build their protective armor. But one study has found that some shelled organisms actually have an easier time building their shells when more carbon dioxide is present, proving the effects can vary widely among different animals.

6. Ruined Ruins

All over the globe, temples, ancient settlements and other artifacts stand as monuments to civilizations past that until now have withstood the tests of time. But the immediate effects of global warming may finally do them in. Rising seas and more extreme weather have the potential to damage irreplaceable sites. Floods attributed to global warming have already damaged a 600-year-old site, Sukhothai, which was once the capital of a Thai kingdom.

5. Survival of the Fittest

As global warming brings an earlier start to spring, the early bird might not just get the worm. It might also get its genes passed on to the next generation. Because plants bloom earlier in the year, animals that wait until their usual time to migrate might miss out on all the food. Those who can reset their internal clocks and set out earlier stand a better chance at having offspring that survive and thus pass on their genetic information, thereby ultimately changing the genetic profile of their entire population.

4. Shrinking Specimens

As temperatures rise, it looks like some species might be shrinking. The shift to the small seems to be happening on the scale of whole communities as well as individual animals: Smaller species are winning out over larger ones; more young animals seem to be present, and some animals seem to be getting smaller for their age. The effect has been seen in both fish and Scottish sheep.

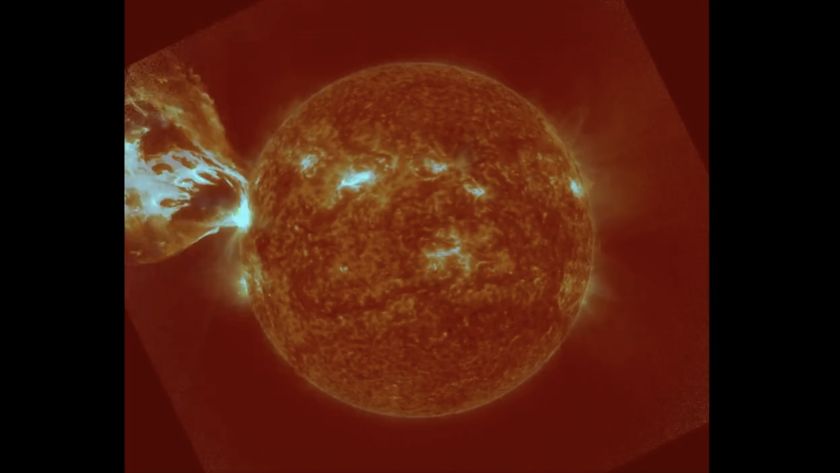

3. Speedier Satellites

Carbon dioxide emissions on Earth are even having effects in space. Air in the atmosphere's outermost layer is very thin, but air molecules still create drag that slows down satellites, requiring engineers to periodically boost them back into their proper orbits. But the amount of carbon dioxide up there is increasing. And while carbon dioxide molecules in the lower atmosphere release energy as heat when they collide, thereby warming the air, the sparser molecules in the upper atmosphere collide less frequently and tend to radiate their energy away, cooling the air around them. With more carbon dioxide up there, more cooling occurs, causing the air to settle. Thus, the atmosphere is less dense and creates less drag on satellites.

2. Rebounding Mountains

Though the average hiker wouldn't notice, the Alps and other mountain ranges have experienced a gradual growth spurt over the past century or so thanks to the melting of the glaciers atop them. For thousands of years, the weight of these glaciers has pushed against the Earth's surface, causing it to depress. As the glaciers melt, this weight is lifting, and the surface is slowly springing back. Because global warming speeds up the melting of these glaciers, the mountains are rebounding faster.

1. Forest Fire Frenzy

While it's melting glaciers and creating more intense hurricanes, global warming also seems to be heating up forest fires in the United States. In western states over the past few decades, more wildfires have blazed across the countryside, burning more area for longer periods of time. Scientists have correlated the rampant blazes with warmer temperatures and earlier snowmelt. When spring arrives early and triggers an earlier snowmelt, forest areas become drier and stay so for longer, increasing the chance that they might ignite.

- Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

- Video – Earth's Changing Oceans

- Top 10 Craziest Environmental Ideas

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.