The 'New' NASA Will Look Back at Earth

NASA's new proposed budget will in part shift the space agency's focus from landing people on the moon back to Earth, with more money slated to go to projects that will help us understand our planet's climate and even plans to re-launch the carbon observatory that failed to launch last year.

The 2011 proposed budget for NASA, announced on Monday, cancels the Constellation program to build new rockets and spacecraft optimized for the moon, but increases NASA's overall budget by $6 billion over the next five years. Of that $6 billion, about $2 billion will be funneled into new and existing science missions, particularly those aimed at investigating the Earth sciences, particularly climate.

"That's about 27 percent of the overall budget over the next five years of the agency [that] will be dedicated to science," said Edward Weiler, head of NASA's Science Mission Directorate at the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The Earth and climate science division will get the bulk of the money allocated to science, and that money will bolster Earth science missions that are either already in the works or proposed, "NASA will be able to turn its considerable expertise to advancing climate-change research and observations," Weiler said today in a press briefing.

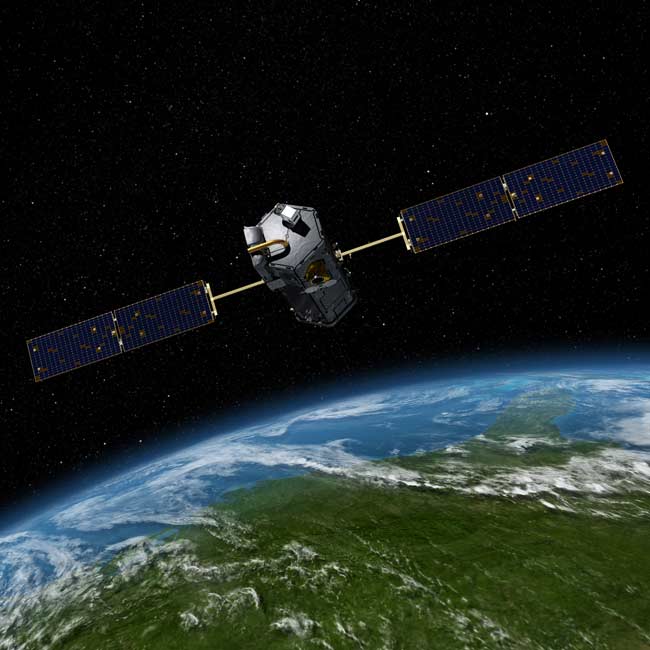

In particular, NASA's budget will allow the agency to re-fly the Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO), which crashed into the ocean near Antarctica just after launch almost a year ago. NASA has decided to give the mission a second chance, because it "is critical to our understanding of the Earth's carbon cycle and its effect on climate change," Weiler said.

OCO was the first satellite built exclusively to map carbon dioxide levels on Earth and help scientists understand how humanity's contribution of the greenhouse gas is affecting global climate change.

Climate scientist Ken Caldeira of Stanford University welcomed the news. "The Orbiting Carbon Observatory is a key piece [of] the monitoring system that we need to keep track of our changing Earth, so that we might better understand the complex interplay of Earth's climate system and carbon cycle, and therefore help to better inform the difficult climate-related decisions that we will need to make over the coming years and decades," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The plans to resurrect the failed satellite began "literally before the sun rose on the night it was lost," said OCO principal investigator David Crisp of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

"Due diligence required that we look at what it would cost and what it would take to fly a backup mission. We knew at that point in time, which was many, many months ago, that there was no identified budget for it, but that didn't mean that we wouldn't try to see if we could find a way to do this," Weiler said.

So Crisp and his team evaluated the possibilities of getting a new OCO back-up in space and decided the best way was to do it exactly the way they did it before.

"This is a carbon copy of the original," Crisp said, with just a few minor, now-obsolete parts replaced.

NASA and Congress approved the plan to keep the option of a new OCO open, so the team has already started gathering and putting in orders for the needed parts. The new budget, if it is approved, will jump start this effort.

"We were just absolutely delighted to see the budget come out," Crisp said. "This is really, really good news for getting the mission back on track."

The new OCO is slated to be rebuilt and launched in 28 months, after Oct. 1 of this year, when the newly approved budget would take effect.

"In space time, that's coming right up," Crisp said, but he is confident that it's a doable schedule, he added.

Crisp told LiveScience he has been receiving many congratulatory e-mails from climate scientists all over the world. "The amount of enthusiasm about this is really heartwarming," he said.

The successor to the OCO will be named OCO-2. The original name was a play on the structure of a carbon dioxide molecule (an oxygen atom attached to a carbon atom attached to another oxygen atom), while the second name plays on the chemical formula of the greenhouse gas, CO2.

OCO won't be the only program that gets a boost from the added funding.

"It will accelerate the development of new satellites to enhance observations of the climate and other Earth systems," Weiler said.

Some of the current missions in development that will benefit are the Global Precipitation Measurement, which will measure global rain, ice and snow patterns, and the Landsat Data Continuity Mission, which aims to continue the efforts of the Landsat satellites in measuring changes in Earth's landmasses. Data from the Landsat satellites are the longest continuous record of Earth's surface as seen from space.

The new budget money will also help operate and launch several planned missions: The Glory mission, to launch later this year, will measure levels of black carbon and other small particles in the Earth's atmosphere that can impact Earth's temperature and climate. The NPOESS Preparatory Project (NPP) mission will take ocean and atmospheric temperatures, humidity measurements, measurements of the biological productivity on land and in the ocean, and investigate the properties of clouds and aerosols, two key uncertainties in climate models. And the Aquarius mission will measure the salinity of the sea surface, gathering more data on this parameter in two months than has been gathered in the last 100 years.

The added funding will also be used to further enhance climate modeling efforts and examine the feasibility of conducting Earth science measurements from the orbiting International Space Station, which will get a longer life under the new NASA plan.

Caldeira lauded the new plans and particularly the shift of resources toward science missions. "Increased funding for Earth observations and climate science signals a welcome redirection of resources to unmanned missions that will have real scientific yield for people who live on Earth today," he told LiveScience.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.