Earthquake Moved California City 31 Inches

Updated Friday, 6/25 at 10:15 a.m. ET

The powerful earthquake that struck Baja California and the southwestern United States in April actually moved an entire California border city, NASA radar images show.

Calexico, Calif., near the U.S.-Mexico border, moved as much as 2 1/2 feet (80 cm) south and down into the ground due to the magnitude-7.2 earthquake on April 4.

Called the El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake, the temblor was centered 32 miles (52 km) south-southeast of Calexico and was the strongest quake to strike the region in nearly 120 years. Two people were killed and hundreds more were injured.

Shaking and moving

It's not the first time a town has moved. The massive 8.8-magnitude earthquake that struck Chile earlier this year moved the city of Concepción at least 10 feet (3 meters) to the west. That quake was the fifth most powerful temblor in recorded history.

Another example of how quakes move as well as shake: In the 6.9-magnitude 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, which occurred along the San Andreas Fault in Northern California, the Pacific plate moved 6.2 feet (about 2 m) to the northwest and 4.3 feet (1.3 m) upward over the North American plate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the long run, earthquakes and shifting fault lines remake the planet. The slip-sliding motion of the San Andreas fault causes San Francisco to move toward Los Angeles at the rate of about 2 inches a year — the same pace at which your fingernails grow. The cities will meet in several million years. (California won't fall into the sea, however.)

Powerful earthquakes can also shift the Earth's axis, changing the length of our planet's days. The Chile quake, for example, shortened the length of an Earth day by 1.26 microseconds.

View from above

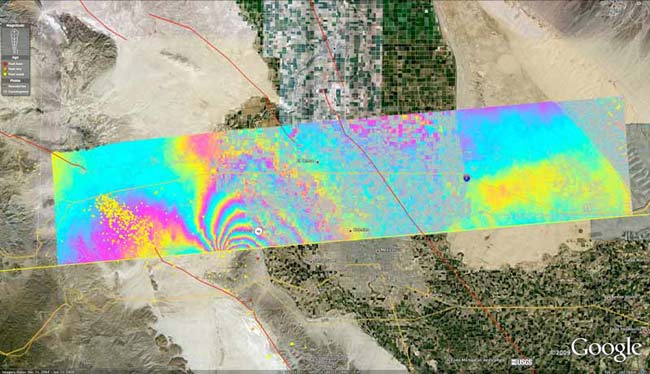

NASA discovered Calexico's comparatively short move by making radar sweeps over the quake-affected region in a Gulfstream-III jet outfitted for science flights.

The aircraft flew 41,000 feet (12,496 meters) above the fault system responsible for the earthquake and recorded how the quake deformed the Earth's surface using the Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar (UAVSAR) developed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

"UAVSAR's unprecedented resolution is allowing scientists to see fine details of the Baja earthquake's fault system activated by the main quake and its aftershocks," said JPL's Scott Hensley, UAVSAR principal investigator at JPL, in a statement. "Such details aren't visible with other sensors." [Radar image of shifted earth]

The biggest land shift caused by the April 4 earthquake was also about 10 feet (3 m). But that occurred well south of the Mexican border, beyond the reach of NASA's airborne radar flight campaign. Radar instruments on Japanese and European satellites, however, managed to record those effects, researchers said.

NASA has been using the radar system to map the San Andreas fault system in California from San Francisco to the Mexico border since spring 2009. The April 4 quake observations came during a campaign that ran between October 2009 and April 13, project officials said.

"The goal of the ongoing study is to understand the relative hazard of the San Andreas and faults to its west like the Elsinore and San Jacinto faults, and capture ground displacements from larger quakes," explained JPL geophysicist Andrea Donnellan, who leads the UAVSAR project to track seismic hazards in Southern California.

The El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake caused substantial damage when it struck. Since then, there have been thousands of aftershocks along related fault lines, including a magnitude-5.7 one on the Elsinore fault on June 14.

NASA researchers are currently working to determine how far north the fault rupture that caused the quake may have reached.

"Continued measurements of the region should tell us whether the main fault rupture has moved north over time," Donnellan said.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that Loma Prieta is located in Northern California, not Southern California.

- 101 Amazing Earth Facts

- Image Gallery: Deadly Earthquakes

- Why Was the Canadian Earthquake Felt So Far Away?

Tariq is the editor-in-chief of Live Science's sister site Space.com. He joined the team in 2001 as a staff writer, and later editor, focusing on human spaceflight, exploration and space science. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times, covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University.