Rainmaking in Middle Eastern Desert: Success or Scam?

Fifty-two unanticipated rain showers in a Middle Eastern desert supposedly occurred because of ionizing devices installed in Abu Dhabi as part of a weather-modification project, a company is claiming.

The still-unproven rainmaking effort comes courtesy of Meteo Systems of Switzerland. The company and some of the researchers involved in the project are hoping to gather enough experimental proof to overcome widespread skepticism among scientists toward such weather modification efforts.

"We have made progress, but for me it is far from claiming 'Yes we have done it,'" said Hartmut Grassl, former director of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and a lead researcher who is helping to monitor the project.

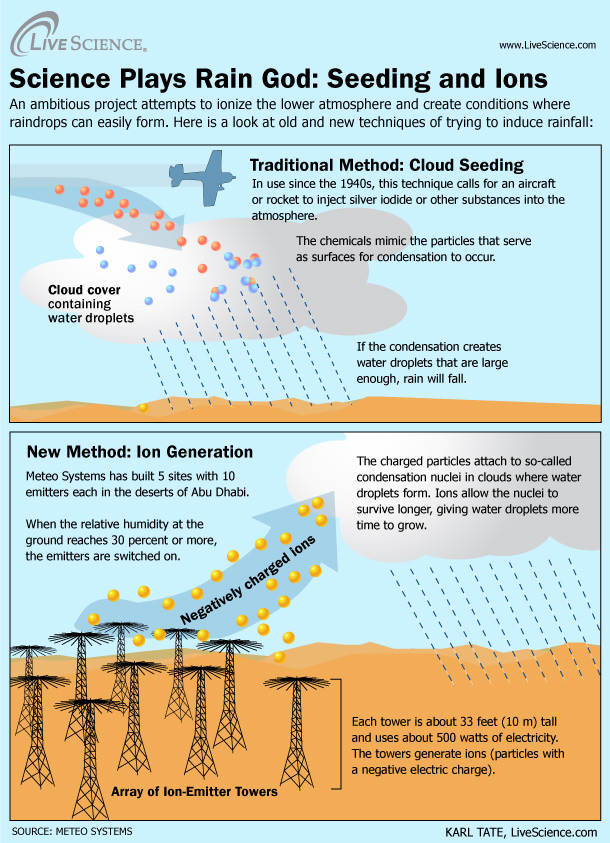

The ionizers look like poles extending 33 feet (10 meters) into the air, with an ionization grid just a few meters wide. Each uses 500 watts of electrical power, or less than what you use turning on an electric stove.

Certain areas of Abu Dhabi experienced a wetter-than-normal summer season, but Grassl cautioned that the jury's still out as to whether it was the work of the ionizers or merely a quirk of nature.

Scientists not involved in the desert-rain project seemed mostly pessimistic about the idea of artificially coaxed raindrops.

"It is very sad that rain enhancement by methods that have no scientific basis (or at least have never been exposed to a scientific evaluation) get the headlines," said Roelof Bruintjes, a meteorologist at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

How it works

Meteo Systems' effort represents the latest wrinkle in weather modification experiments that have been running for some time now.

The primary type of weather alteration, which began in the 1940s, is called cloud seeding, where an aircraft or rocket is used to inject silver iodide or other substance into the atmosphere. The chemicals mimic ice nuclei, or the particles that serve as surfaces for condensation to occur (where gas turns into a liquid). If the condensation creates large enough water droplets, rain will fall.

Rather than chemicals, Meteo Systems used ionization in its attempts to boost rainfall. In theory, ions, or charged particles, attach to the condensation nuclei in clouds and enable them to survive longer in the atmosphere. The longer they survive, the more time water droplets have to grow on their surfaces.

The company set up five ionizing sites in Abu Dhabi, each with 10 so-called emitters that can send trillions of these cloud-forming ions into the atmosphere.

Grassl and his colleagues are monitoring the cloud-forming effects by radar, satellite and global analyses from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. They have also been tracking local meteorology at all the ionizing sites, and measuring the electrical fields created by the ionizers.

Rain gauges that measure the levels of rainfall are less extensive in the region, Grassl explained in a phone interview. That means the scientists must rely upon the other methods to monitor the success or failure of the ionizing sites.

Skeptics abound

Jérôme Kasparian of the University of Geneva in Switzerland has done work on weather modification, but was not aware of the rain project and hasn't seen it published in a scientific journal.

"What can be said is it is really astonishing that they could get rain at what I read [in the news] was 30 percent relative humidity," Kasparian told LiveScience. While the humidity makes sense since the scientists were in a desert, it is so low that "you don't expect water condensation, so you must give the water a very, very strong incentive to condense."

In work published in 2010 in the journal Nature Photonics, Kasparian and his colleagues showed that by beaming ultra-short laser pulses into the atmosphere, they could create water droplets at a relative humidity as low as 70 percent. "At this stage we get droplets but not yet raindrops," Kasparian said. "The droplets that we obtained aren't sufficiently big to fall down to the ground."

Confusion about the 30 percent relative humidity cited in news reports was later cleared up by Grassl. He explained in a phone interview that the 30 percent relative humidity was at ground level, rather than up in the atmosphere where clouds form.

"If you talk about 30 percent relative humidity at the ground, then in a hot climate you will have close to 100 percent relative humidity [near the cloud-forming boundaries of the atmosphere]," Grassl said.

As a result, the ion emitters were turned on whenever atmospheric levels of humidity reached 30 percent or more relative humidity at the ground.

To rain or not to rain

Strange as it sounds, using ionization for weather-modification attempts is not new. So-called ionization antennas began with a Russian scientist and have since been marketed internationally through several companies, according to Bruintjes at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Such past attempts mostly dried up for lack of funding and results. Bruintjes similarly threw cold water on the Meteo Systems effort and declared himself "very skeptical" about the company's claims.

He also pointed to a report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), an agency of the United Nations, which cautioned against believing claims regarding weather modification.

"It should be realized that the energy involved in weather systems is so large that it is impossible to create cloud systems that rain, alter wind patterns to bring water vapor into a region, or completely eliminate severe weather phenomena," according to the WMO report.

The WMO report also said that weather-modification technologies such as "ionization methods" had no sound scientific basis and "should be treated with suspicion." The report was updated by weather-modification experts during a meeting in Abu Dhabi in 2010.

Proceed with caution

Grassl agreed that weather-modification efforts ranging from cloud seeding to ionization have not been proven, despite countries such as Russia and China regularly deploying cloud seeding.

"Yes, they claim all sorts of fantastic things, but it is not proven," Grassl said. "The same is true for the method we're assessing now."

But he does see some promising signs in Meteo Systems' effort so far, even if he conceded that many questions must be answered before the company can truly promise a working rainmaker. He and other researchers will soon gather at a workshop in Germany to discuss the ongoing effort.

Meteo Systems has spent several million euros (1 euro = 1.33 USD) so far on half a year's worth of operations. Grassl hopes that the company might get additional funds from Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyen, Emir of Abu Dhabi and president of the United Arab Emirates.

"It should be done over at least two full years at this place [in Abu Dhabi] and at other places as well," Grassl said. "Otherwise you cannot claim this is working very well."

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu and Managing Editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner.