Visualization shows exactly how face masks stop COVID-19 transmission

Without a mask, droplets produced during coughing can travel up to 12 feet. With a mask, this distance is reduced to just a few inches.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A dramatic new visualization shows exactly why it's a good idea to wear a face mask to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus.

Without a mask, droplets produced during coughing can travel up to 12 feet (3.7 meters), the visualization revealed, but with a mask, this distance is reduced to just a few inches in the best cases.

The simulation, which was described today (June 30) in the journal Physics of Fluids, also reveals that some cloth masks work better than others at stopping the spread of potentially infectious droplets.

"The visuals used in our study can help convey to the general public the rationale behind social-distancing guidelines and recommendations for using face masks," study lead author Siddhartha Verma, an assistant professor at Florida Atlantic University's College of Engineering and Computer Science, said in a statement.

Related: 13 coronavirus myths busted by science

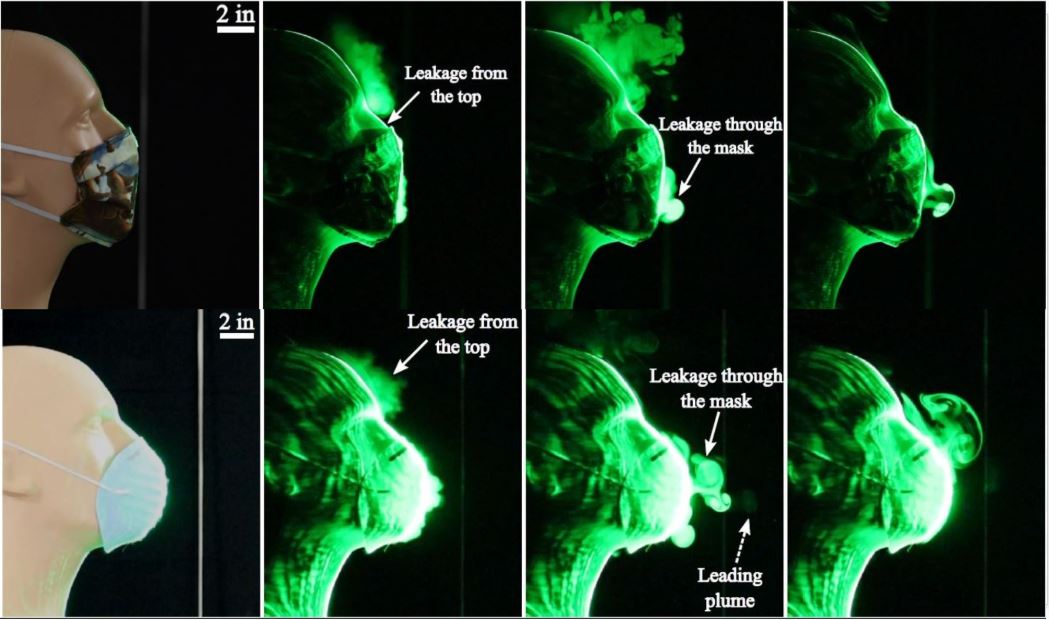

To simulate a cough, the researchers connected a mannequin's head to a fog machine (which creates a vapor from water and glycerin), and used a pump to expel the vapor through the mannequin's mouth. They then visualized the vapor droplets using a "laser sheet" created by passing a green laser pointer through a cylindrical rod. In this setup, simulated coughs appear as a glowing green vapor flowing from the mannequin's mouth.

The researchers then placed several types of non-medical masks on the mannequin head to test their effectiveness at blocking these "coughs." These included a homemade mask stitched with two layers of cotton fabric used for quilting (with 70 threads per inch), a single-layer bandana, a loosely folded cotton handkerchief and a non-sterile cone-style mask sold in pharmacies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that, with no mask covering, the simulated coughs traveled up to 12 feet in 50 seconds.

The homemade stitched cotton mask — with its multiple layers and snug fit — reduced the spread of the droplets the most, although there was some leakage at the top of the mask between the nose and the cloth material. When the mannequin wore this mask, droplets traveled only about 2.5 inches (6.35 centimeters) forward from the face. The cone-style mask also worked well, with droplets traveling just about 8 inches (20 cm) from the face.

However, the single-layer bandana (made from an elastic T-shirt material) and folded handkerchief were less effective. Droplets leaked through the mask material and traveled more than 3.5 feet (1 m) with the bandana and more than a foot (0.3 m) with the handkerchief.

Still, "although the non-medical masks tested in this study experienced varying degrees of flow leakage, they are likely to be effective in stopping larger respiratory droplets" from dispersing, the authors wrote in their paper.

"Promoting widespread awareness of effective preventive measures [for COVID-19] is crucial at this time as we are observing significant spikes in cases of COVID-19 infections in many states, especially Florida," Verma said.

- 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

- Going viral: 6 new findings about viruses

- The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus