Naked Mole-rats Hold Clues to Human Aging

VIRGINIA BEACH, VA—They wouldn't win any beauty contests, but naked mole-rats would take home the crown for longevity. And research into human aging might draw from knowledge of the wrinkly subterranean creatures.

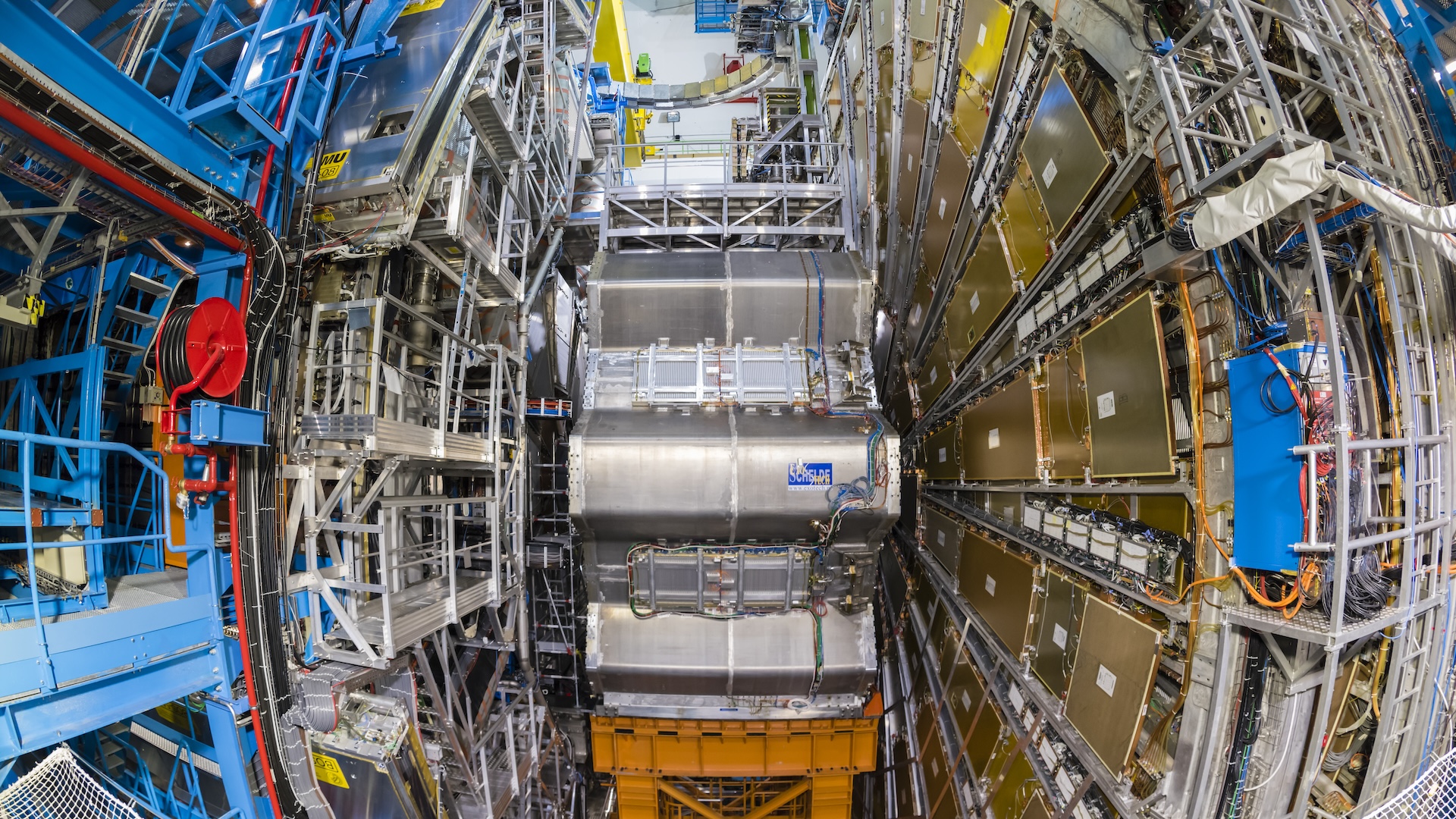

No bigger than a stick of butter, mole-rats [image] long outlive similar-sized rodents. They're known to approach age 30.

Now scientists have gained some insight into this longevity: Mole-rats simply deal with the kind of cellular damage that life normally brings about.

"The naked mole-rat, with its surprisingly long life span and remarkably delayed aging, seems like the perfect model to provide answers about how we age and how to retard the aging process," said Rochelle Buffenstein of the City College of New York. "This animal may one day provide the clues to how we can significantly extend life."

- They almost never go above ground and are nearly blind.

- They dig out burrows with oversized buckteeth.

- They live in colonies of up to 300 individuals, with one breeding female similar to a queen bee.

- Within their tunneling burrows, they delineate a separate toilet area, where feces and urine get stored.

- They farm underground tubers by feeding from one end, plugging the end with soil and then feeding from the tuber’s other end.

Buffenstein presented her team's research here at a meeting of the American Physiological Society.

Aging cells

Humans and other animals are constant victims to oxidative stress. In the body, oxygen splits into single oxygen atoms, known as free radicals due to their unpaired electrons. They scavenge the body to nab or donate an electron, causing damage to cells, proteins and genetic material. Antioxidants produced by the body help to neutralize the free-radical attack.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Since mole-rats live several times longer than other rodents their size, scientists would expect them to exhibit either lower oxidative stress or a greater ability to defend against the attack by free radicals, perhaps by employing more antioxidants.

Buffenstein's team compared two-year-old naked mole-rats to four-month-old mice, selecting ages that were equivalent relative to the animals’ maximum life spans. Turns out the mole-rats had more oxidative damage to biological molecules, including more DNA and protein damage in the kidney and liver. Plus, the mole-rats had lower levels of oxidative neutralizers.

Yet somehow they live on.

Unknown mechanism

Buffenstein suspects the mole-rat is able to fend off acute bouts of oxidative stress, and that may be more important than dealing with routine injury caused by daily levels of oxidative stress.

“It’s like saying if something really unexpected came along and instead of having a nervous breakdown, I just fixed it," Buffenstein told LiveScience.

Further research is needed to figure out exactly how the mole-rats live with the damage caused by oxidative stress.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.