Humans and Neanderthals Might Have Interbred

As modern humans spread across Europe tens of thousands of years ago, they may have interbred with Neanderthals, creating hybrids, according to a new study of ancient human bones from Romania.

Anthropologists have long wondered what happened when the two species met as modern humans spread from Africa into Neanderthal territory in Eurasia: did the populations interbreed or did modern humans simply replace their cousins?

The specimens examined and dated for the first time in this study show that “at least in Europe, the populations blended,” said study author Erik Trinkaus of Washington University.

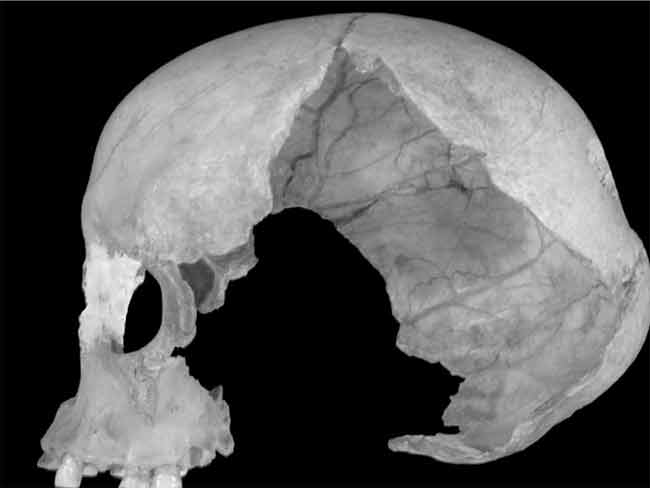

The study compared the fragments, including a skull [image] and jaw [image], to bones of Neanderthals, early modern humans in Africa before they spread, and in Europe afterward. Trinkaus said that he and his colleagues found certain features that could have only come from Neanderthals, because early modern humans lost them before they spread from Africa.

They found a swelling at the back of skull, called an occipital bun, which is the result of differential brain growth and is commonly found in Neanderthal skulls. Also, the arrangement of muscle attachment at the back of the jaw was a trait of Neanderthals.

This evidence of interbreeding shows that “[the two groups] saw each other as socially appropriate mates,” Trinkaus said.

Early modern humans and Neanderthals were two branches of the human family tree that differed primarily in the anatomical pattern, with humans eventually becoming the dominate pattern. Though humans and Neanderthals were different species, Trinkaus points out that most closely related species that haven not been separated for long amounts of time can still breed and produce fertile offspring.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It is possible that people with European ancestry could also have Neanderthal ancestry, according to Trinkaus, though how much is uncertain.

Prior to this study, the remains were largely forgotten because “there was serious doubt as to their age,” Trinkaus said. When the remains were discovered in a Romanian cave in the early 1950s, prior to carbon dating, they were not embedded in a rock layer that might indicate their age. Because the bones essentially looked like those of an early modern human, they received little attention inside Romania and were unknown outside the country.

Some scientists dispute that there was any overlap between the two species, but Trinkaus dismisses these claims. “There was an overlap,” Trinkaus said, though anthropologists are unsure as to how long the two species co-existed.

According to Trinkaus, anthropologists have “securely dated” modern humans in Romania at 35,000 years ago and Neanderthals in Spain at 30,000 years ago.

“We don’t have a site where we have a human and a Neanderthal buried next to each other,” Trinkaus said. “I’m still waiting for that.”

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.