Kids Offer Advice to Stressed-Out Parents

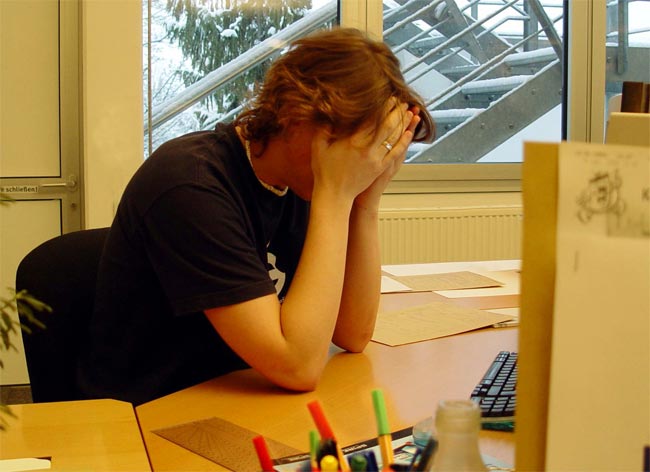

NEW YORK—Working parents might think they leave it at the office, but kids know better. Whether adults realize it or not, their job-related stress affects their children, scientists said here this week at the annual meeting of the American Psychoanalytic Association.

Over the past 30 years, time spent at the office has jumped 10 hours a week. And one in three employees in the United States reports feeling chronically overworked, said Ellen Galinsky, president of the Families and Work Institute in New York.

“By all of our measures, jobs have become much more hectic and demanding," Galinsky said. "People feel like they don’t have enough time to get everything done.” And that includes spending time, let alone quality time, with children.

- Do you find yourself being more cynical, critical and sarcastic at work?

- Have you lost the ability to experience joy?

- Do you drag yourself into work and have trouble getting started once you arrive?

- Have you become more irritable and less patient with co-workers, customers or clients?

- Do you feel that you face insurmountable barriers at work?

- Do you feel that you lack the energy to be consistently productive?

- Do you no longer feel satisfaction from your achievements?

- Do you have a hard time laughing at yourself?

- Are you tired of your co-workers asking if you're OK?

- Do you feel disillusioned about your job?

- Are you self-medicating—using food, drugs or alcohol—to feel better or to simply not feel?

- Have your sleep habits or appetite changed?

- Are you troubled by headaches, neck pain or lower back pain?

Source: Mayo Clinic

Even if parents bring no actual work home, they definitely carry the residual impact of their day in the office.

“If we’re cooking dinner and looking at our kids’ homework, and we’re also thinking about a discussion we had with a boss, are we working or not?” Galinsky said.

Kids talk

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Galinsky studied a nationally representative sample of more than 600 parents and 1,000 children ranging from 3rd to 12th grade. Interviewers asked children what would be their one wish if they could change how a father or mother’s work affected each child. More than half of parents guessed their children would wish for more parent time.

Wrong answer. Most children wished their parents would be less stressed from work.

“If our parents were less tired and stressed, I think that the kids would be less tired and stressed,” said one of the children interviewed.

Little detectives

Unbeknownst to parents, children play detective to snag personal and work information. Galinsky found that some kids would eavesdrop from the top of the stairs or even listen on extensions to private phone conversations, with the “mute” key pressed.

Subtle cues, such as a parent’s down-turned expression or heavy footsteps, also led kids to easily detect their parents’ moods.

“I know when my mom has a bad day because when she picks me up from after school she doesn’t smile,” one young girl told interviewers. “She has a really frustrated look on her face.”

De-stress

Quality time at home makes a difference.

“It doesn’t occur to parents that it’s the emotional climate around working or being at home that have an impact,” said Jennifer Stuart of New York University Psychoanalytic Institute.

“There are a number of things to help people manage their stress,” Galinsky told LiveScience. For instance, take time out when you get home to unwind with the proverbial warm bubble bath. If all else fails, talk to your children (if they’re old enough) and let them know you had a bad day at work, Galinsky suggested. The most important piece of information to impart to kids is that your bad mood isn’t their fault, she said.

One boy interviewed in Galinsky’s study offered another idea: “If you’re stressed out and tired, take a little nap. But don’t take a long one.”

- Job Stress Fuels Disease

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

- The Keys to Happiness, and Why We Don’t Use Them

- The Most Popular Myths in Science

- Life’s Little Mysteries

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.