Humans Have Astonishing Memories, Study Finds

If human memory were truly digital, it would have just received an upgrade from something like the capacity of a floppy disk to that of a flash drive. A new study found the brain can remember a lot more than previously believed.

In a recent experiment, people who viewed pictures of thousands of objects over five hours were able to remember astonishing details afterward about most of the objects.

Though previous studies have never measured such astounding feats of memory, it may be simply because no one really tried.

"People had never tested whether people could remember this much detail about this many objects," said researcher Timothy Brady, a cognitive neuroscientist at MIT. "Nobody actually pushed it this far."

When they did push the human brain to its limits, the scientists found that under the right circumstances, it can store minute visual details far beyond what had been imagined.

Those circumstances include looking at images of objects that are familiar, such as remote controls, dollar bills and loaves of bread, as opposed to abstract artworks.

Another factor that seemed to help was motivation to do well: The participant who scored highest won a small prize of money (the researchers refused to say exactly how much).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"You have to try," said MIT co-author Talia Konkle. "You have to want to do it."

The study, funded by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship, and a National Research Service Award, was detailed in the Sept. 8 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

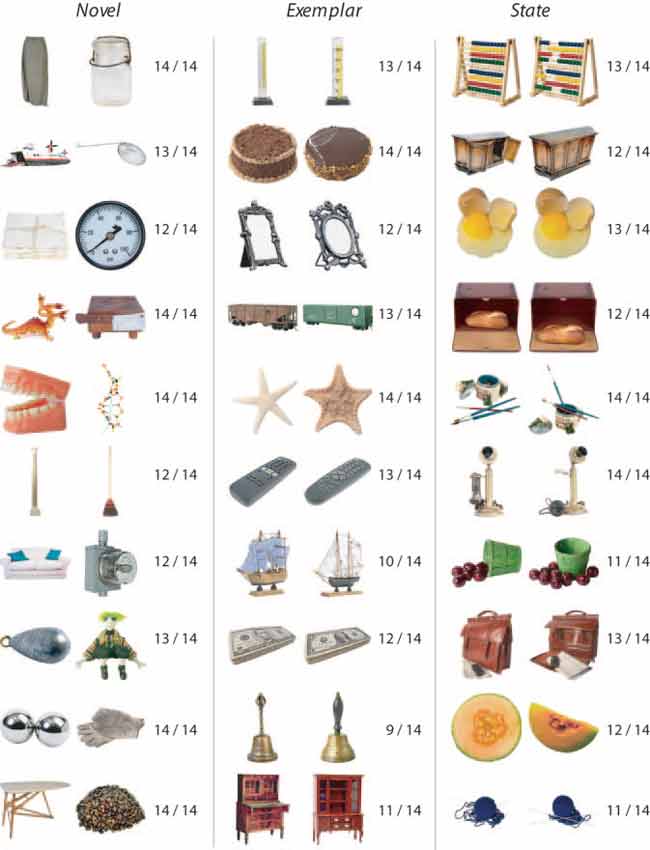

In the experiment, 14 people ranging from age 18 to 40 viewed nearly 3,000 images, one at a time, for three seconds each. Afterwards, they were shown pairs of images and asked to select the exact image they had seen earlier.

The test pairs fell into three categories: two completely different objects, an object and a different example of the same type of object (such as two different remote controls), and an object along with a slightly altered version of the same object (such as a cup full and another cup half-full). Stunningly, participants on average chose the correct image 92 percent, 88 percent and 87 percent of the time, in each of the three pairing categories respectively. Though 14 subjects may not sound like a huge sample, the fact that they each recalled the objects with very similar rates of success suggests the results are not a fluke.

"To give just one example, this means that after having seen thousands of objects, subjects didn’t just remember which cabinet they had seen, but also that the cabinet door was slightly open," Brady said.

Even the researchers didn't expect quite such high recall rates.

"We had the intuition that it might be possible, but we were surprised by the magnitude of the effect," said study leader Aude Oliva, also of MIT. "These numbers, higher than 85 and 90 percent, impressed us and also impressed a lot of people who heard about the work."

So now that we know the brain's memory is so fantastic, are we all out of excuses for forgetting friends' birthdays?

Luckily not, Brady said.

"To some extent it's about attention, actively encoding specific details into memory," he told LiveScience. "If we tried really hard we actually could remember when someone's birthday was: if you say to yourself, 'The birthday is on this day and that relates to these other things that I remember.'"

Basically, he said, we can remember most things we put our minds to, if we invest enough attention and effort into trying to store them in the first place.

- Video: Attention Training

- Video: A Turn-off Switch for Alzheimer's

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind