Depression Linked to Brain Thinning

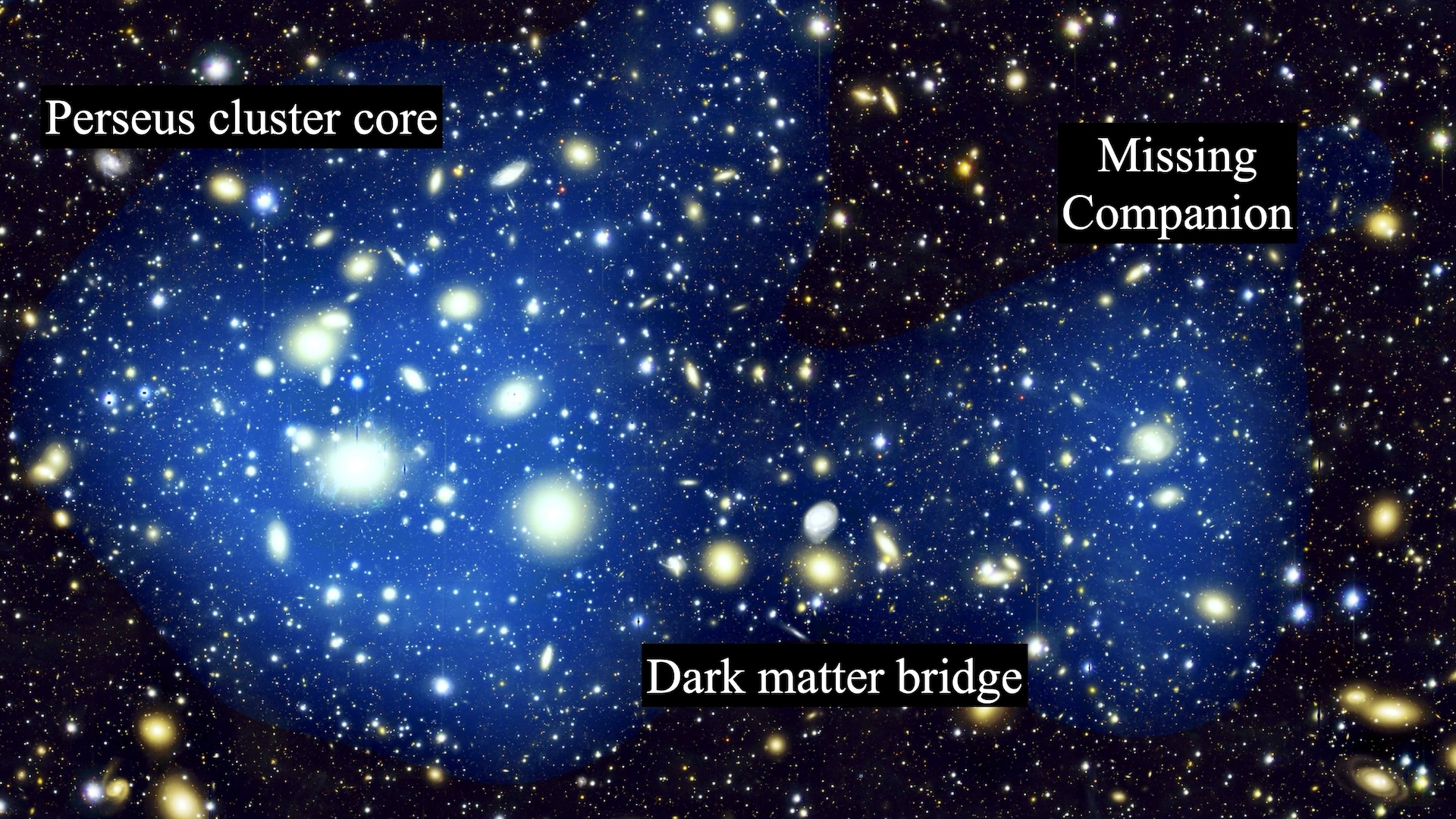

A structural difference in the brain, in particular a thinning of the right hemisphere, is linked to a higher familial risk for depression, according to a new study.

The researchers found that people at high risk of developing major depression had a 28 percent thinning of the right cortex, the brain's outermost surface, compared to people with no known risk. The result comes from a large imaging study conducted at Columbia University Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Major depression occurs in 8 to 12 percent of the population in most countries at some point in their lives, and it runs in families. It is associated with increased risk for death as a result of suicide and other causes.

The reduction surprised the researchers, which they say is on par with the loss of brain matter typically observed in people with Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia.

"The difference was so great that at first we almost didn't believe it. But we checked and re-checked all of our data, and we looked for all possible alternative explanations, and still the difference was there," said Dr. Bradley Peterson, director of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and director of MRI Research in the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, and first author of the study.

How it might work

The thinner cortex may increase the risk of developing depression by disrupting a person's ability to pay attention to, and interpret, social and emotional cues from other people, Peterson said. Additional tests measured each person's level of inattention to and memory for such cues. The less brain material a person had in the right cortex, the worse they performed on the attention and memory tests.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It is unclear if these findings apply to all forms of depression, and not just major depressions, Peterson said.

Antoine Bechara, professor of psychology at the University of Southern California, called the new study "exciting" because it points to a problem in the cortex, rather than just one involving chemicals or neurotransmitters.

"One puzzling thing to me is that this study points to areas all over the cortex, whereas more and more people think that depression may be linked more to problems in the prefrontal cortex, and especially the medial part (like the anterior cingulate)," Bechara noted. "This study does not contradict these ideas at all." In fact, he said, it fits with them, "except that it seems less specific and it includes much broader brain regions. It remains possible that from all these areas, only the key areas such as the prefrontal cortex and the insula are the most important, and the rest may be less relevant."

Who is predisposed to depression?

The study compared the thickness of the cortex by imaging the brains of 131 subjects, aged 6 to 54, with and without a family history of depression. Structural differences were observed in the biological offspring of depressed subjects but were not found in the biological offspring of those who were not depressed.

One of the goals of the study, published online by the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was to determine whether structural abnormalities in the brain predispose people to depression or are a cause of the illness.

The study found that thinning on the right side of brain did not correlate with actual depression, only an increased risk for the illness. It was subjects who exhibited an additional reduction in brain matter on the left side, who went on to develop depression or anxiety.

"Our findings suggest rather strongly that if you have thinning in the right hemisphere of the brain, you may be predisposed to depression and may also have some cognitive and inattention issues," Peterson said. "The more thinning you have, the greater the cognitive problems. If you have additional thinning in the same region of the left hemisphere, that seems to tip you over from having a vulnerability to developing symptoms of an overt illness."

It all suggests a very complex picture.

Bechara said the left-right aspect of the study's findings are intriguing. "On one hand it is very striking that it affects one side (the right) side, but not the other," he said. "The other is that it seems (at least on the surface) somewhat contradictory to some older theories of depression," which are controversial but found an association between the brain's left hemisphere and happier outlooks, and between the right hemisphere and a withdrawn or sad outlook.

He also said there are alternate interpretations of Peterson's findings. Cortical thinning could be preceded by underlying problems in neurotransmitter systems such as dopamine, serotonin and noreadrenaline, which supply nerves to the cortices — if the chemical is low, then the area may become less functional and thinner.

"Once these cortical areas become thin, then functionally they may begin to resemble a patient with lesions (from, for example, strokes) in those same cortical regions — such signs include poor working memory, poor attention, poor decision making, and poor social behavior, all of which are signs also seen in patients with depression," Bechara told LiveScience.

Potential treatments

The findings point to potential treatments or novel uses of already existing treatments for people with major depression, which doctors distinguish from dysthymia, a milder but chronic form of depression, Peterson said. For example, behavioral therapies that aim to improve attention and memory and/or stimulant medications currently used for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may be treatments for people who have familial depression and this pattern of cortical thinning, Peterson said.

"This conjecture is entirely speculative at this point, but it is a logical hypothesis to test based on the findings from this study," he said.

This study was supported by funding from a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health, National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Sackler Institute at Columbia University.

Overall risk factors for depression

Experts can argue the details, but there are two types of risk factors for depression — genetics and environment. There are genetic variations among individuals in terms of how much dopamine or serotonin they have in their body, Bechara said.

In the environmental area, it is key that the human brain, specifically the prefrontal cortex, does not become fully mature until very later on in life (in teens and maybe even early 20s).

Because this region is still developing it can be more vulnerable: Early stress (such as separation from mother, social isolation, and the like) can cause these "still developing" brain regions to wire up in an abnormal way, Bechara said.

- All About Depression

- Video – Attention Training for Kids

- 5 Ways to Beef Up Your Brain

Catquistadors: Oldest known domestic cats in the US died off Florida coast in a 1559 Spanish shipwreck

'Vaccine rejection is as old as vaccines themselves': Science historian Thomas Levenson on the history of germ theory and its deniers

Astronomers discover giant 'bridge' in space that could finally solve a violent galactic mystery