Brain's Link Between Sounds, Smells and Memory Revealed

Sights, sounds and smells can all evoke emotionally charged memories. A new study in rats suggests why: The same part of the brain that's in charge of processing our senses is also responsible, at least in part, for storing emotional memories.

For instance, the smell of turkey could conjure up a smile as it reminds you of a joyful Thanksgiving, while the sound of a drill could make you start in fear, since it may be linked to your last dental appointment.

Previously, scientists had not considered these sensory brain regions all that important for housing emotional memories, said study researcher Benedetto Sacchetti, of the National Institute of Neuroscience in Turin, Italy.

While the new findings are preliminary, they suggest these sensory brain regions might play a role in certain fear and anxiety disorders, Sacchetti said. For instance, dysfunction in these areas might make it hard for someone to differentiate between sights, sounds and other stimuli that they should and should not be afraid of, resulting in generalized fear and anxiety.

The results will be published in the August 6 issue of the journal Science.

Sights, sounds and shocks

The sensory cortex of the brain receives and interprets signals from our eyes, nose, ears, mouth and skin. The sensory cortex is divided into the primary and secondary cortex. The secondary sensory cortex is responsible for processing more complex information about a stimulus, such as distinguishing between different musical tones.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

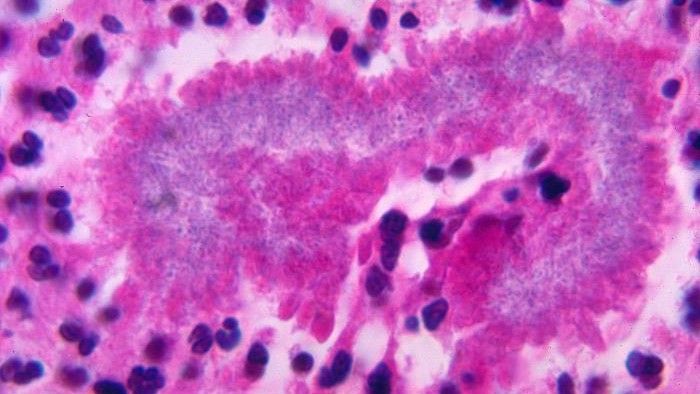

In their first experiment, Sacchetti and his colleagues trained rats to associate a sound with an electric shock. The trained animals would freeze upon hearing the sound. A month later, the researchers created lesions in some of the rats' brains on the secondary auditory cortex, meant to disrupt this region responsible for processing sound. (A month is quite a long time in the life of a rat, which usually lives around three years).

The lesion-bearing rats froze much less often than those without lesions, indicating the lesioned rats had trouble recalling the fear memory from a while back.

This suggests sensory information — a particular sound — is coupled with emotional information — a memory of fear — and stored in the auditory cortex as a bundle. This allows the sound to acquire an emotional meaning.

The researchers saw the same results for rats with lesions in the parts of their brain responsible for interpreting sights and smells, the visual and olfactory cortices, respectively. In these trials, the rats were trained to fear flashing lights and the smell of vinegar.

In all these experiments, rats with lesions were still able to form new fear memories, suggesting that the sensory cortices are needed to store, but not create, emotional memories.

Emotional memories

The researchers further showed that the auditory, visual and olfactory cortices each store memories related to the specific sense they process. Lesions in the olfactory cortex did not prevent trained rats from remembering to associate a sound with the fear memory.

Experiments even revealed that the sensory cortices store information specific to the emotional meaning of the sound, sight, or smell.

Rats startle when they first hear a sound, regardless of whether it's linked to a scary event. But eventually, in a process called habituation, they grow accustomed to it. The team wanted to find out if these sensory memories that didn't involve fear were still stored in the secondary cortices. So they habituated the rats to a sound with no electric shock. One month later, lesions were made on the rats' secondary cortices for all senses. The lesioned rats still didn't startle upon hearing the sound, suggesting the secondary cortices only store memories if the stimulus is tied to an emotion. These sensory memories must be stored in another brain region, the researchers figure.

The researchers note the secondary cortices are likely not the only regions involved in storing emotion memories tied to the senses. Other areas, such as the amygdala, thought to play a key role in processing fear, could participate as well.

The researchers note that while rats are considered a good model for studies like these, more work is needed to determine whether the findings apply to humans, the researchers say.

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- 7 Thoughts That Are Bad For You

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.