Artificial Human Ovary Created

A lab-grown ovary has successfully matured human eggs and could eventually be used to help women conceive.

The artificial ovary could play a role in preserving the fertility of women facing cancer treatment in the future, said study researcher Sandra Carson, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Women & Infants Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Immature eggs could be salvaged and frozen before the onset of chemotherapy or radiation, and then matured in the artificial ovary.

"I think this will be a way that we'll be able to mature eggs, but it's not going to be next month," Carson told LiveScience, adding that she hopes in the next five years the method will be used in clinical practice.

The development will also provide a living laboratory of sorts for looking into basic questions about how healthy ovaries work and how exposure to toxins, such as phthalates, can disrupt the organ and its function.

Ovaries are almond-size organs (most women have two) in which eggs mature before being released down the fallopian tubes, ready to be fertilized. But when aiming to recreate one, the scientists had to look under the hood at key details.

"An ovary is composed of three main cell types, and this is the first time that anyone has created a 3-D tissue structure with triple cell line," Carson said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

She said her goal was never to invent an artificial organ, per se, but merely to create a research environment where she could study how the three types of ovary cells interact.

But then Carson learned about special Petri dishes created in the lab of Jeffrey Morgan, associate professor of medical science and engineering at Brown University. The dishes are made out of a moldable gel meant to coax cells into certain shapes. The cells can't attach to the micro-mold and so instead they attach to one another within the confines of the custom-shaped molds.

"In a typical Petri dish, cells grow as one layer on the surface of the dish," Morgan said in a telephone interview. "And in our 3-D dish the cells grow as clusters of cells, they self-assemble to form a 3-D structure."

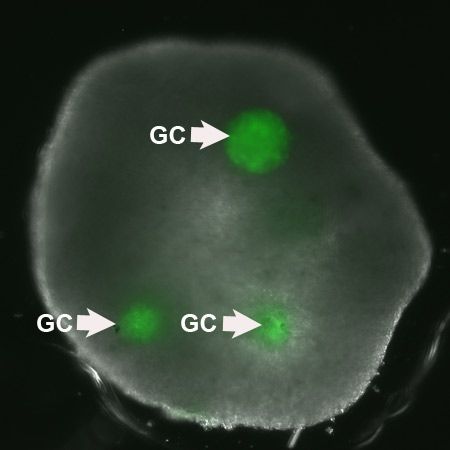

The two researchers collaborated to create the lab ovary. First they formed honeycombs of theca cells, one of two key types in the ovary, donated by patients ages 25 to 46 at the hospital. After the theca cells grew into the honeycomb shape, spherical clumps of donated granulosa cells were inserted into the holes of the honeycomb together with human egg cells (oocytes), also donated by patients. In a couple days the theca cells enveloped the granulosa and eggs, mimicking a real ovary.

In experiments the structure, which is about the diameter of a pencil eraser, was able to nurture eggs from the so-called early antral follicle stage to full maturity. None of the eggs in the study were fertilized with sperm.

The scientists detail their results online Aug. 25 in the Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics that describes the innovation.

The research was supported by the division of reproductive endocrinology & infertility at the Women & Infants' Hospital of Rhode Island, and by a grant from the Rhode Island Science and Technology Council.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.