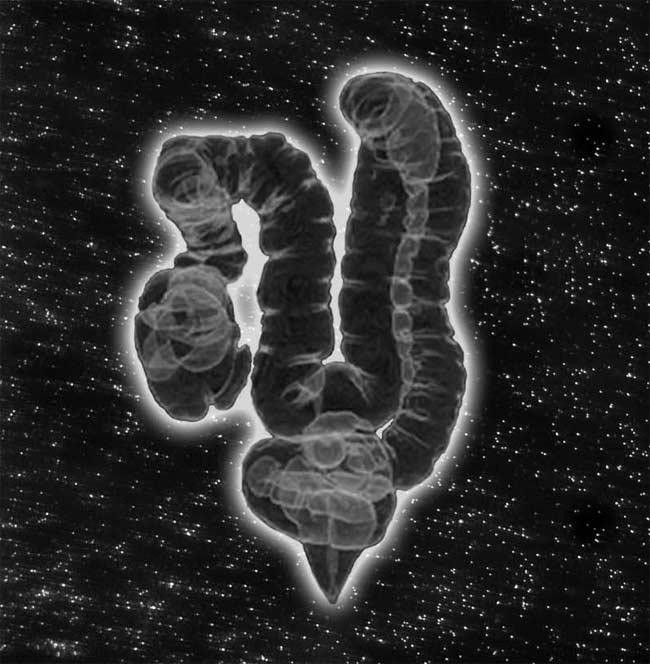

Your Poop Is Unique: Gut Viruses Different in Every Person

Like a fingerprint, the virus communities in the human gut are unique to each individual, a new study on poop DNA suggests. Even identical twins have very different collections of viruses colonizing their lower intestines.

This is in contrast to bacterial communities, which are similar in related individuals, the researchers say. (While bacteria can live and reproduce on their own, viruses consist of genetic material packaged inside a capsule structure and can only reproduce inside a host.)

The study sheds light on the largely unexplored world of viruses living in the lower intestine. Most of these "friendly" viruses, which don't cause diseases, make their home inside bacteria already living in the gut. These viruses are thought to influence the activities of gut microbes, which among their other benefits, allow us to digest certain components of our diets, such as plant-based carbohydrates, that we can't digest on our own.

In recent years, a number of projects worldwide have been initiated to catalog the microbes that live in and on the human body, with the goal of understanding the relationship between microbial communities (including viruses and bacteria) and overall health and disease.

The new research, published this week in the journal Nature, suggests such projects should also focus on the viruses that co-exist and co-evolve with bacteria and other microbes that normally live in our bodies. For instance, these viruses might act as barometers for the overall health of the gut microbial community as it responds to challenges or recovers after an illness or therapeutic intervention.

Studying stool

Most of the information scientists have about viruses that live together with bacteria comes from studies of their outdoor habitats, like the ocean, said study researcher Jeffrey Gordon of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. "There, the lifestyle of viruses can be described as [a] 'predator-prey dynamic' with a continuous evolutionary battle of genetic change affecting viruses and their microbial hosts," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To learn more about the viruses in the human gut, the scientists turned to poop.

Gordon and his colleagues decoded the DNA isolated from viruses in stool samples provided by four pairs of identical twins and their mothers. The investigators sequenced the viral DNA — or viromes — from samples collected at three different times over a one-year period, which enabled them to track any fluctuations in viral communities over time.

They also sequenced the DNA of all the microbes (including bacteria) — the microbiome — in the samples, which allowed them to compare the viral and bacterial communities in the lower intestines.

Remarkably, more than 80 percent of the viruses in the stool samples had not been previously discovered. "The novelty of the viruses was immediately apparent," Gordon said.

The intestinal viromes of identical twins were about as different as the viromes of unrelated individuals. However, family members shared a certain degree of the same bacteria species.

Within each individual, the viromes remained stable and persisted over the one-year study. This also differed from the bacterial communities, which experienced greater fluctuations.

In other words, the viruses in the stool specimens did not appear to exhibit the predator-prey lifestyle seen in environment communities, Gordon said. Instead of trying to kill each other, the bacteria and viruses appear to be engaged in a mutually beneficial relationship — the bacteria provide a way for the viruses to reproduce and the viruses may provide extra genes that benefit their bacterial hosts.

Future outlook

The researchers now plan to study the viromes in the developing intestines of infant twins – identical and fraternal – from different families to determine how viruses first "set up shop" in the gut ecosystem and how they are influenced by the nutritional status of their human hosts.

In addition, to better understand viral lifestyles throughout the length of the intestine, they are introducing these viruses into mice that only contain human gut microbes.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents