Organic Labels May Trick Dieters Into Eating More

The "organic" label skews people's perceptions about food in ways that might promote obesity, a new study finds.

The results show people sometimes assume organic foods are lower in calories and so it's OK to indulge in organic cookies more often than regular ones. Exercise was also deemed less necessary after eating organic desserts.

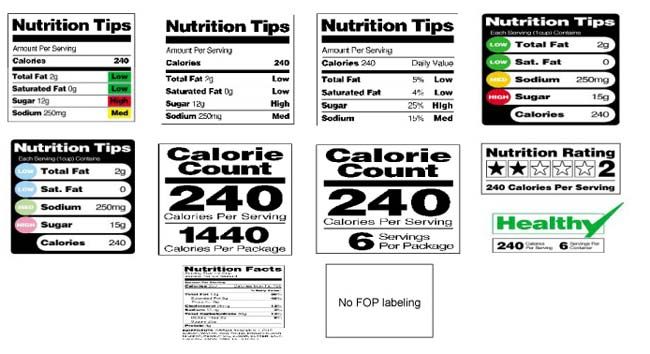

The findings are in line with previous work showing food labels can spur misperceptions. For instance, labeling a food as "low fat" can lead people to infer that it also has fewer calories, and foods marked as having "low cholesterol" can be judged as having less fat. Also, there is a strong tendency for Americans to associate the concept of "organic" with healthiness, the researchers say.

"I think the take-home point is that, in everyday judgments and decisions, organic foods might be treated as something they're not," said study researcher Jonathon P. Schuldt, a graduate student in psychology at the University of Michigan. "They might be treated as health foods that are lower calorie when in fact that's not always the case."

Perceiving foods to have fewer calories might lead some to eat more than they otherwise would, he said. And the association with healthiness might cause some to think they can substitute organic foods, even dessert foods, for weight loss behaviors such as exercise, he said.

However, more research is needed to determine if this way of thinking actually does make people eat more and promotes weight gain.

Sales of organic foods in the United States have increased rapidly over the past two decades, rising from $1 billion in 1990 to $25 billion in 2009. The label refers to the way the food is processed, and not to its fat or calorie content.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Schuldt and his colleague Norbert Schwarz, also of the University of Michigan, conducted two experiments to see whether "organic" translates to "fewer calories" in consumers' minds.

In the first study, 114 college students were asked to read nutrition labels for cookies. The cookies were described as either "Oreo cookies," or "Oreo cookies made with organic flour and sugar." Both were labeled as containing 160 calories. The participants were asked to rate whether they thought the cookies contained fewer calories or more calories than other cookie brands, on a scale from 1 (fewer calories) to 7 (more calories). They were also asked whether these cookies should be eaten more or less often than other cookie brands.

The cookies described as "organic" were rated as having fewer calories than the conventional Oreo cookies compared with other brands. The organic cookies received an average rating of 3.9 while the traditional cookies received an average rating of 5.17.

The participants also thought the organic cookies could be eaten more often than the non-organic counterparts.

The impact of the organic label on people's calorie judgments was largest for those with pro-environment views, or those who would likely value organic food production in the first place, Schuldt said.

In the second study, 215 college students read a story about a character who wanted to lose weight, but wanted to skip her usual after-dinner run. Participants read she had eaten either an organic or regular non-organic dessert. Then they rated whether it was OK for her to skip the run.

The participants were more lenient toward the character if she had eaten the organic dessert instead of the conventional one.

"These findings suggest that 'organic' claims may not only foster lower calorie estimates and higher consumption intentions, but they may also convey that one has already made progress toward one's weight loss goal," the researchers write in an upcoming issue of the journal Judgment and Decision Making.

- Top 7 Biggest Diet Myths

- Top 10 Good Foods Gone Bad

- When Health Food Is Unhealthy

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.