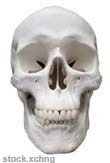

Ancient Skeletons Reveal First Baby Boom

The onset of agriculture led to baby booms worldwide, a new study suggests.

Researchers have long thought the transition from nomadic hunter-gathers to a sedentary farming economy, which occurred at different times in different parts of the world from about 9,000 to 1,000 BC, led to increases in birthrate wherever it took hold. But the idea had never been verified.

The initial goal of the new research was to provide evidence for the increase in human numbers using skeletons in cemeteries throughout Europe and North Africa, explained Stephan Naji, a graduate student from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris.

"The signal for this transition was clearly detected in the form of a birth rate explosion around the time of the invention of agriculture," Naji said.

Immature skeletons

Previous studies had shown that with the advent of agriculture, the number of archeological remains increased dramatically, leading researchers to believe that there was a growth in population. But the scale and timing of the population surges remained unknown. Demographers investigated the issue using historical documents such as census and parish data, but this information is incomplete, Naji explained.

Looking at data from 38 cemeteries in Europe and North Africa, Naji and colleagues had previously found that the proportion of immature skeletons increased from 20 percent to 30 percent around the time agriculture was invented.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In a growing population, the proportion of immature individuals, dead or alive, is high," said Jean-Pierre Bocquet-Appel, research director at the National Center for Scientific Research, Paris. "In a declining population, this proportion is low."

In their recent work, Bocquet-Appel and Naji looked at data from 62 prehistoric cemeteries in North America and observed a similar trend to that of Europe and North Africa. The shifts occurred over a period of 600 to 800 years but at different times in history.

"During the economic change from foraging to farming, the mortality profiles of immature skeletons in European and North American cemeteries are strikingly similar," Bocquet-Appel said.

More time to procreate

There was more food with farming to support more people, and the sedentary nature of life allowed women to become more fertile and thus raised birthrate.

In nomadic societies, women carried their children around with them and often breastfed until the ages of 3 or 4. This delayed the return of women's menstruation cycle. With a farming lifestyle and less mobility, children spent less time in their mother's arms, reducing their breastfeeding to 1 to 2 years and allowing women to have more children.

Bocquet-Appel and Naji hope to look at all the primary centers of agricultural invention around the world in order to find out if transitions similar those in Europe and North America occurred elsewhere.

"Furthermore, we are gathering data to explore the impact of this transition on population health," Naji told LiveScience.

The work will be detailed in the April issue of the journal Current Anthropology.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality