Megaflood Created Great Divide Between Britain and France

The cultural rift between Britain and France endures as an amusing mystery for many, but the physical divide between them can now be blamed on two ancient floods.

About 450,000 years ago, a "megaflood" breached a giant natural dam near the Dover strait and began the formation of the English Channel , according to a study detailed in the July 19 issue of the journal Nature. Following this first disastrous flood, a second deluge finished the job.

"The first was probably 100 times greater than the average discharge of the Mississippi River," said Sanjeev Gupta, a geologist at Imperial College London and co-author of the study. "But that's a conservative estimate—it could have been much larger."

Gupta said his team's findings quash previous, evidence-thin theories about how the island became severed from mainland Europe.

"Britain has been an island for only a very short time period, and we've put together the first clear evidence that the valley system in the English Channel was carved by a megaflood," Gupta said.

Chalky dam

Prior to the first megaflood, which originated from an enormous lake of freshwater in what is now the North Sea, a quaint river valley was the only waterway obstructing France and Britain. Inattentive to building materials, nature contained the monstrous, ice-locked lake with chalky stone.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Some freak event, whatever it was, caused the dam to fail at some point," Gupta said, although he noted that the breach may have resulted from simply too much water built up behind the dam.

When the 19-mile-wide barrier failed, the deluge that followed carved an impressive basin 33 feet deep and almost 31 miles wide in a matter of weeks.

"The dimensions are enormous," Gupta said. "This was when sea levels were about 100 meters (328 feet) lower than today, when a lot of ocean water was locked up in ice sheets."

Double deluge

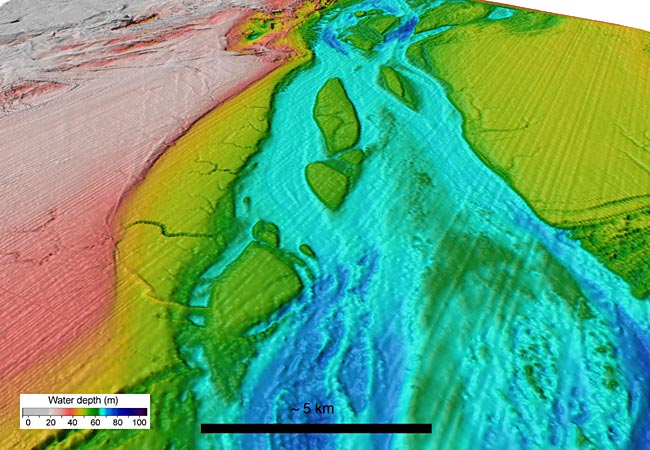

An even larger and more cataclysmic event, however, outdid the first megaflood, sometime prior to 180,000 years ago. This second deluge created the characteristic English Channel bottom seen today, according to the study.

The second torrent added insult to injury, whittling polished mesa-like islands out of the basin floor. Gupta said such structures are tell-tale signs of megafloods.

"The Channeled Scablands, in eastern Washington state, is an area where a huge ice-dammed lake created some of these extraordinary features," Gupta said. "They're analogous to what we see underwater in the English Channel."

Gupta is uncertain what initiated the second megaflood, but he thinks a large embankment of glacial deposits could have released freshwater that etched out canyon-like valleys.

Old evidence, new discovery

Making the discovery, Gupta explained, arose out of sheer boredom.

"I went to the library and came across an older book laying out this theory," Gupta said, noting that the author had little evidence to support it. Yet Gupta realized advances in sonar technology allowed mapping the English Channel's floor in high-resolution, which was done for purposes of ship safety. It was simply a matter of bringing the two pieces together, he pointed out.

"We were astonished by what we found. Quite frankly, we have better maps of Mars than we do of shallow seas around Britain," he said.

Gupta explained three dominant English-Channel-forming theories are shored up by the findings. Glaciers couldn't have carved out the Channel because the polar ice sheets never crept that far south. He explained that erosion by river or ocean also can't account for the underwater valley because it is too wide and has structures characteristic of a major flood.

"The valley cuts across a large number of rock types, simply ignores the different layers," he said, explaining that only a rapid, enormous and powerful flood can account for the bedrock-scouring features.

In the future, Gupta and his team plan to look for remnants of the enormous natural dam.

"We want to map the ancient lake out, see if there are any other features we've missed," Gupta said. "We may be able to find large boulders left behind from the dam. Be prepared for big discoveries in the future—this is a whole new avenue of research."

- Top 10 Natural Disaster Threats

- Timeline: The Frightening Future of Earth

- Date Pinned Down for Ancient Antarctic Flood