Tenochtitlán: History of Aztec Capital

Tenochtitlán was an Aztec city that flourished between A.D. 1325 and 1521. Built on an island on Lake Texcoco, it had a system of canals and causeways that supplied the hundreds of thousands of people who lived there.

It was largely destroyed by the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés after a siege in 1521, and modern-day Mexico City now lies over much of its remains. In a 1520 letter written to King Charles I of Spain, Cortés described the city that he would soon attack:

“The city is as big as Seville or Cordoba. The main streets are very wide and very straight; some of these are on the land, but the rest and all the smaller ones are half on land, half canals where they paddle their canoes.” (From "An Age of Voyages: 1350-1600," by Mary Wiesner-Hanks, Oxford University Press, 2005)

He noted the city's richness, saying that it had a great marketplace where “sixty thousand people come each day to buy and sell...” Its merchandise included “ornaments of gold and silver, lead, brass, copper, tin, stones, shells, bones and feathers ...”

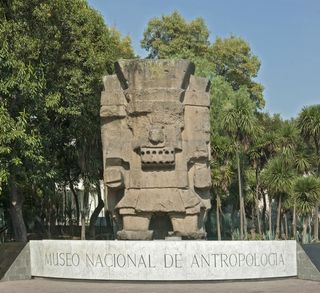

In June 2017, officials with Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) announced they had discovered an ancient ceremonial ball court and an Aztec temple dedicated to the wind god Ehécatl, both of which were likely in use from A.D. 1481 until 1519 in Tenochtitlan, in modern-day Mexico City. Nearby the ball court, archaeologists discovered the neck bones of 30 infants and children. The findings were part of the Urban Archaeology Program, in which archaeologists are uncovering the remains of the razed. Aztec capital.

Origins of Tenochtitlán

According to legend, the Aztec people left their home city of Aztlan nearly 1,000 years ago. Scholars do not know where Aztlan was, but according to ancient accounts one of these Aztec groups, known as the Mexica, founded Tenochtitlán in 1325.

The legend continues that Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, the sun and human sacrifice, is said to have directed the Mexica to settle on the island. He “ordered his priests to look for the prickly pear cactus and build a temple in his honor. They followed the order and found the place on an island in the middle of the lake ...” writes University of Madrid anthropologist Jose Luis de Rojas in his book "Tenochtitlán: Capital of the Aztec Empire" (University of Florida Press, 2012).

De Rojas notes that the “early years were difficult.” People lived in huts, and the temple for Huitzilopochtli “was made of perishable material.” Also in the beginning, Tenochtitlán was under the sway of another city named Azcapotzalco, to which they had to pay tribute.

Political instability at Azcapotzalco, combined with an alliance with the cities of Texcoco and Tlacopan, allowed the Tenochtitlán ruler Itzcoatl (reign 1428-1440) to break free from Azcapotzalco’s control and assert the city’s independence.

Over the next 80 years, the territory controlled by Tenochtitlán and its allies grew, and the city became the center of a new empire. The tribute that flowed in made the inhabitants (at least the elite) wealthy. “The Mexica extracted tribute from the subjugated groups and distributed the conquered lands among the victors, and wealth began to flow to Tenochtitlán,” writes de Rojas, noting that this resulted in rapid immigration into the city.

The city itself would come to boast an aqueduct that brought in potable water and a great temple dedicated to both Huitzilopochtli (the god who led the Mexica to the island) and Tlaloc, a god of rain and fertility.

Aztec social organization

The people of Tenochtitlán were divided into numerous clan groups called calpulli (which means “big house”), and these in turn consisted of smaller neighborhoods. “Usually, the calpulli was made up of a group of macehaultin (commoner) families led by pipiltin (nobles)” writes California State University professor Manuel Aguilar-Moreno in his book "Handbook to Life in the Aztec World" (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Fray Diego Durán, a Spaniard who lived in Mexico a few decades after Cortés’ conquest, wrote that King Motecuhzoma (or Montezuma) I, who reigned from 1440 to 1469, created an education system where every neighborhood had to have a school or temple to educate youth.

In those places “they will learn religion and correct comportment. They are to do penance, lead hard lives, live with strict morality, practice for warfare, do physical work, fast, endure disciplinary measures, draw blood from different parts of the body, and keep watch at night...” (Translation by Doris Heyden)

Another feature of Tenochtitlán’s society was that it had a strict class system, one that affected the clothes people wore and even the size of the houses they were allowed to build. “Only the great noblemen and valiant warriors are given license to build a house with a second story; for disobeying this law a person receives the death penalty...” Fray Durán wrote.

Among the people considered to be in the lower classes were the porters the city relied on. The lack of wheeled vehicles and pack animals meant that the city’s goods had to be brought in by canoe or human lifting. Surviving depictions show porters carrying loads on their backs with a strap secured to their forehead.

Trade and currency

As Tenochtitlán’s empire grew so did its trade. Aguilar-Moreno writes that a pivotal moment in the city’s economic history was its capture of the nearby city of Tlatelolco in 1474. He notes that Tlatelolco was a “trade city” and that the “union of these two cities made the site of Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco the economic and political center of the Valley of Mexico.” [Related: Aztec Conquerors Reshaped Genetic Landscape of Mexico]

Instead of minted currency people bartered for goods using “cacao beans for small transactions, cotton blankets for mid-range ones, and quills filled with gold dust for large business operations,” writes researcher Carroll Riley in her book "Rio del Norte: People of the Upper Rio Grande From Earliest Time to the Pueblo Revolt" (University of Utah Press, 1995).

She notes that metallurgy played a major role in Tenochtitlán’s economy and society. “Metallurgy was now well established for copper, silver, and gold; there was even enough metal to allow copper to be used for agriculture and industrial tools as well as for armaments and jewellery.”

Aztec writing

The writing used by the people of Tenochtitlán, and by other Aztec groups, was what researchers call “pictorial.” This means that “it is composed predominately of figural images that bear some likeness to, or visual association with, the ideas, things, or actions they represent,” writes Elizabeth Boone in her book "Stories in Red and Black: Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs" (University of Texas Press, 2000). She notes, however, that this system of writing “also contains abstractions and other marks that were arbitrarily assigned certain meanings, meanings unrelated to their likeness.” [Related: Amazing Aztecs Were Math Whizzes Too]

The Aztecs used this writing system to create “codices” made from the bark of fig trees. “Hundreds of manuscripts existed at the time of the Aztecs. All but eleven disappeared with the arrival of the Europeans. The majority were destroyed in a bonfire ordered by [Fray] Juan de Zumárraga in 1535,” writes Houston Museum of Natural Science curator Dirk Van Tuerenhout in his book "The Aztecs: New Perspectives" (ABC-CLIO, 2005). He notes that the Spanish priests objected to the Aztec religious content in the codices.

Templo Mayor

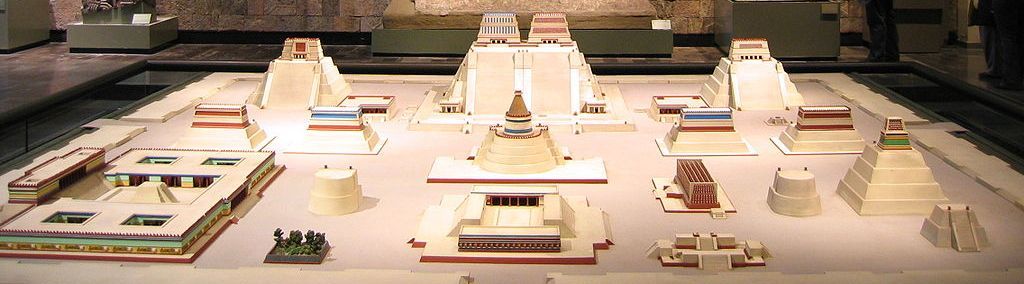

At the heart of the city was a sacred area surrounded by a wall. “Within the enclosure were more than seventy buildings, and these were surrounded by a wall decorated with images of serpents, called a coatepantli,” writes de Rojas.

Archaeologists are still trying to determine exactly what this sacred area looked like, and how it changed over time, but scholars know for sure that the greatest structure was a place that the Spaniards called the “Templo Mayor” (main temple). As mentioned earlier, it was dedicated to the gods Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc.

“Standing about ninety feet [27 meters] high, the majestic structure consisted of two stepped pyramids rising side by side on a huge platform. It dominated both the Sacred Precinct and the entire city,” writes Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Heidi King in an online article.

Two long, broad, staircases led to the top of monument where two temples stood. “The temple structures on top of each pyramid were dedicated to and housed the images of the two important deities,” writes King.

It was a place where great, and gruesome, rituals were performed. “We know of human sacrifice at the top of the Templo Mayor, but it also was the scene of athletes and dancers moving gracefully in and around platforms and braziers,” writes University of Utah professor Antonio Serrato-Combe in his book "The Aztec Templo Mayor: A Visualization" (The University of Utah Press, 2001).

The human sacrifice element should not be underestimated, though. Serrato-Combe points out that there were two Tzompantli (skull racks) located near the Templo Mayor, a bigger one to the west and a smaller one to the north.

A Spanish account of a sacrifice reads that “the high priest who wielded the sacrificial knife struck the blows that smashed through the chest. He then thrust his hand into the cavity which he had opened to rip out the still beating heart. This he held high as an offering to the sun...” (Account by Fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, from the book "The Aztec Templo Mayor: A Visualization")

The fall of Tenochtitlán

Michael Smith, a professor at the State University of New York at Albany, notes that when Cortés landed in Mexico in 1519 he was, initially, greeted with gifts of gold from Tenochtitlán’s ruler Motecuhzoma (or Montezuma) II. The king may have been hoping that the gifts would appease the Spanish and make them go away, but it had the opposite effect.

“The gold, of course, made the Spaniards more anxious than ever to see the city. Gold was what they sought,” Smith writes in his book "The Aztecs" (Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

Cortés pushed on to Tenochtitlán, where Motecuhzoma II again gave the conquistador a warm welcome. Cortes then repaid the ruler by taking him prisoner and trying to rule the city in his name. This arrangement quickly soured with dissident groups naming Cuitlahuac, the king’s brother, to take over from the soon-to-be-killed Motecuhzoma.

Cortés fled the city on June 30, 1520, but within several months started marching back with a great army to conquer it. Smith notes that this force was made up of 700 Spaniards and 70,000 native troops who had allied themselves with the Spanish.

“Much of the Spanish success was owed to the political astuteness of Hernando Cortés, who quickly divined the disaffection towards the Mexica that prevailed in the eastern empire.”

This army laid siege to Tenochtitlán, destroying the aqueduct and trying to cut off food supplies to the hundreds of thousands of people in the city. Making matters worse is that the inhabitants of the city had recently been decimated by a smallpox plague to which they had no immunity.

“The illness was so dreadful that no one could walk or move. The sick were so utterly helpless that they could only lie on the beds like corpses...” wrote Friar Bernardino de Sahagún (from "The Aztecs" book).

The sheer size of Cortés force, their firepower and the plague ravaging Tenochtitlán made victory inevitable for the Spaniards. The city was theirs in August 1521. Smith notes that the Tlaxcallan soldiers that were in Cortés force “went on to massacre many of the remaining inhabitants of Tenochtitlán.”

Smith notes that an elegy for the city was later written, it reads:

Broken spears lie in the roads; we have torn our hair in grief. The houses are roofless now, and their walls are red with blood. We have pounded our hands in despair against the adobe walls, for our inheritance, our city, is lost and dead. The shields of our warriors were its defense, but they could not save it.

(Translated from the Nahuatl language by Miguel León-Portilla)

The ancient city had fallen, and a new Spanish colonial city would be built atop its ruins.

— Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor

Editor's Note: This reference article was first published on May 23, 2013. It was updated with new discoveries on June 15, 2017.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.