Settlement of Americas a 3-Act Play

The epic journey by which the Americas were first settled has been a great mystery for centuries. Did it happen by land or by sea? Did it happen one dozen or so millennia ago or three dozen?

The answer might be "yes."

New findings reveal the settling of the New World did not come in a single burst, as is suggested by most theories, but was, in a way, a play with three acts, each separated by thousands of generations.

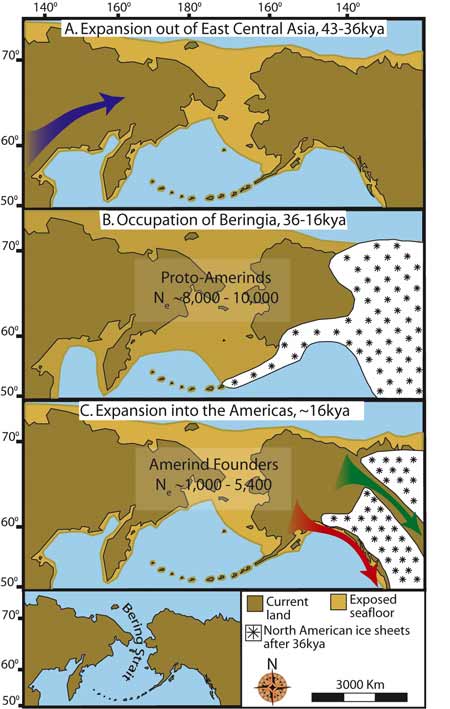

The first stage of this voyage involved a gradual migration of people from Asia through Siberia starting about 40,000 years ago into Beringia, a once-habitable grassland populated with steppe bison, mammoths, horses, lions, musk oxen, sheep, wooly rhinoceros and caribou that nowadays lies submerged under the icy waters of the Bering Strait.

The second phase of the journey was basically a layover in Beringia.

"Two major glaciers blocked their progress into the New World. So they basically stayed put for about 20,000 years," said researcher Connie Mulligan, a molecular anthropologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville. The population there apparently did not grow or shrink much during this era, which suggests Beringia "wasn't paradise, but they survived."

In the final act, "when the North American ice sheets started to melt and a passage into the New World opened, we think they left Beringia to go to a better place," Mulligan explained, resulting in a rapid expansion into the New World about 15,000 years ago. Their research suggests the New World was settled by approximately 1,000 to 5,000 people — a substantially higher number than the 100 or fewer individuals of some prior estimates.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research will be detail online Feb. 13 in the journal PLoS ONE.

How did the researchers come up with their findings? Well, DNA allows scientists to deduce the history of populations. For instance, mutations that all New World populations have in common with each other and no one else means they share a common ancestry, suggesting there was just one wave of migration into the Americas, as opposed to several unrelated waves.

However, the molecular evidence was confusing as to when this wave of migration took place. DNA accumulates mutations over time, serving like a clock, but some DNA suggested people came to the New World about 13,000 years ago, while other sequences hinted at 30,000 or more years ago.

Mulligan and her colleagues' new analysis of DNA from Native American and Asian populations seem to help resolve conflicts in past research by suggesting a long waiting period on the doorstep to the New World.

As for Beringia, sea levels rose about 10,000 to 11,000 years ago as the peak of the ice age waned, submerging the land and creating the Bering Strait that now separates the New World from Siberia with at least 60 miles of open, frigid water.

The expansion into the New World may have occurred by land after the ice sheets covering what is now Canada began to retreat 14,000 to 17,000 years ago, the scientists noted. However, they added that glaciers on the northwest Pacific coast of North American also might have receded by about 17,000 years ago, thus presenting a viable coastal route by sea to the continent. "It doesn't have to be an either-or thing. They could have used both routes," Mulligan said.

Innovative work

Anthropologist and population geneticist Henry Harpending at the University of Utah, who did not participate in the research, said he found the work innovative.

"The idea that people were stuck in Beringia for a long time is obvious in retrospect, but it has never been promulgated," said Harpending, who found it very plausible that people were stuck in Beringia "for thousands of years."

Although this new theory could resolve some of the conflicting results scientists have come up with over the years, "I don't pretend this inclusive approach will make us any friends, just more critics," Mulligan told LiveScience.

For instance, one criticism Mulligan anticipates is the fact that "20,000 years in Beringia is a long time. Some people will say, 'Get real — where's the evidence?' We would say that there's no one that does arctic underwater archaeology."

Researcher Andrew Kitchen added, "Our theory predicts much of the archaeological evidence is underwater. That may explain why scientists hadn’t really considered a long-term occupation of Beringia."

Mulligan noted one might also contend that any evidence of such a 20,000-year stay in Beringia might have left evidence in Siberia or Alaska. "But we envision a small population there that probably left a relatively light footprint on the landscape," she explained. "And the areas we're talking about — Siberia, Alaska — there's no way to argue that researchers have covered those areas thoroughly, with their incredibly harsh climates."

- North America Settled by Just 70 People

- Ancient People Followed 'Kelp Highway' to America

- How Did America Get its Name?