Female Shaman's Grave Loaded with Goodies

A 12,000-year-old burial site in Israel contains offerings that include 50 tortoise shells and a human foot, and appears to be one of the earliest known graves of a female shaman.

The remains were discovered in a small cave called Hilazon Tachtit, which functioned as a burial site for at least 28 individuals. The grave woman, likely a shaman, was separated from the other bodies by a circular wall of stones.

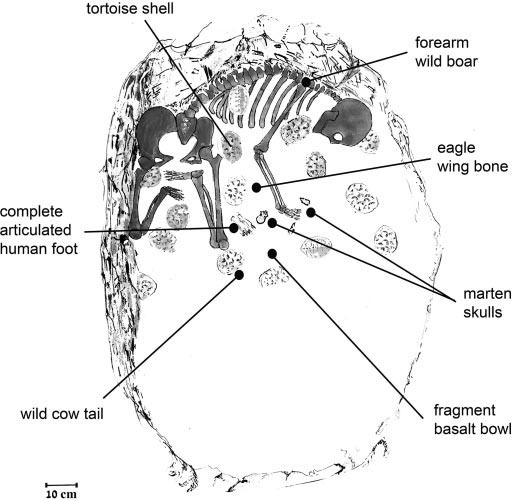

Other grave goodies buried within that wall included tail vertebrae from an extinct type of cattle called an auroch, skulls from two stone martens (members of the weasel family), bony wing parts from a golden eagle, the forearm of a wild boar and a nearly complete pelvis from a leopard.

"What was unusual here was there were so many different parts of different animals that were unusual, that were clearly put there on purpose," said researcher Natalie Munro, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Connecticut.

Great pains were likely taken long ago to collect the animal remains for the grave, not to mention the long trek that must have been made from the closest domestic site at the time, about 6 miles (10 km) away, say the researchers.

This care along with the animal parts point to the grave belonging to both an important member of the society and possibly a healer called a shaman, the researchers conclude in their research published this week by the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Such healers mediate between the human and spirit worlds, often summoning the help of animal spirits along their quests, according to the researchers.

Life was tough

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The woman was about 45 years old when she died and based on measurements of the skull and long bone, she stood at about 4.9 feet (1.5 meters). Wearing of her teeth and other aging signs on the bones suggested the woman was relatively old for her time. And she likely had a limp or dragged her foot, the researchers speculate, due to the fusion of the coccyx and sacrum along with deformations of the pelvis and lower vertebrae.

The human foot lying alongside the body came from an adult individual who was much larger than the women.

"What's interesting is it's only the foot," Munro told LiveScience. "She hasn't been disturbed, but a part of another human body was definitely put into the grave. It could be related to the fact they were moving body parts around sometimes, but we don't know why."

At least 10 large stones had been placed on the head, pelvis and arms of the buried individual, which the researchers suggest helped to protect the body and keep it in a specific position, or possibly to hold the body in its grave.

Scattered around the body and beneath it were tortoise shells. Before arranging the shells inside the grave during the burial ritual, humans cracked open the tortoise shells along the reptiles' bellies (so as not to crack the back part of the shell) and sucked out the meat, possibly for food.

"So they took the insides out by breaking the belly, but they left the back intact and that was probably meaningful," Munro said.

Rituals begin

The woman was part of the Natufian culture, a group of hunter-gatherers who lived from 15,000 to about 11,500 years ago in the area that now includes Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

The finding is particularly interesting since the Natufians were on the verge of becoming a more sedentary, farming society.

Finding an early shaman grave during this transition makes sense, Munro said.

"With the beginning of agriculture we seem to see an intensified ritual behavior," Munro said. "When things change dramatically, people tend to try to reestablish the legitimate order of things by using ritual and religion to deal with change."

She added, "These people are starting to live in more permanent communities; they're in more contact with one another from day to day. It's not surprising that we start to see evidence for those ritualized behaviors at this point in time."

- Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal with the Dead

- Roots of Voodoo: Why Sarkozy is Getting Skewered

- Cults, Religion and the Paranormal

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality