'Lost' Letters Reveal Twists in Discovery of Double Helix

Rediscovered letters and postcards highlight the fierce competition among scientists who discovered DNA's famous double-helix structure and unraveled the genetic code.

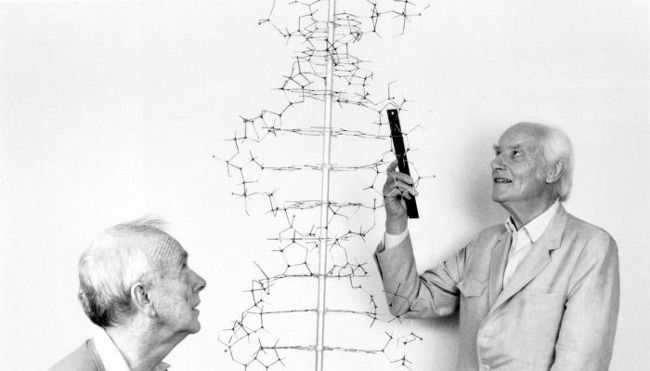

Francis Crick and James D. Watson shared a 1962 Nobel Prize with Maurice Wilkins for their work on revealing the structure of the DNA molecule that encodes instructions for the development and function of living beings. But formerly lost letters kept by Crick add more color to the well-known rivalries between Wilkins and the Crick-Watson duo.

"The [letters] give us much more flavor and examples illuminating the characters and the relations between them," said study researcher Alexander Gann, editorial director at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press in New York. "They're consistent with what we already believed, but they add important details."

A fourth researcher credited with initial DNA work, Rosalind Franklin, died of cancer in 1958 and was never nominated for a Nobel Prize. She and her male colleagues did not get along despite their professional collaboration, as seen in some rather blunt messages contained within the new material.

"I hope the smoke of witchcraft will soon be getting out of our eyes," Wilkins wrote to Crick and Watson in 1953, as Franklin prepared to leave Wilkins' lab for Birbeck College in London.

Nine boxes of Crick's material turned up mixed in with the correspondence of a colleague, Sydney Brenner, who had donated his personal documents to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Library in New York. Researchers knew that much of Crick's earlier correspondence had been lost, but no one suspected it would emerge in Brenner's files.

Rival labs

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The rediscovered material contains several nuggets about the race between rival labs to develop a DNA model in the early 1950s. Wilkins and Franklin worked at King’s College London, while Crick and Watson did their research at the Cavendish Lab of Cambridge University.

Watson and Crick built an incorrect triple-helix model of DNA in 1951, after Watson saw a lecture by Franklin where she showed crystallographic X-ray images she had taken of DNA. The overconfident Watson had failed to take notes, and so he underestimated the amount of water in the DNA structure.

That led to a temporary agreement that Watson and Crick should not pursue a model of DNA for the time being, because the duo had merely used data from the rival King's College lab. Wilkins and Crick exchanged newly uncovered letters that show Wilkins alternating between a formal, typed letter about the agreement and a handwritten note expressing more personal anguish over the situation.

Yet Crick and Watson still managed to come off as confident in a rediscovered letter to Wilkins, and even include a verbal jab.

Rather than end the letter by praising Wilkins for now having a clear chance to solve the DNA structure, they crossed it out and wrote: "…So cheer up and take it from us that even if we kicked you in the pants it was between friends. We hope our burglary will at least produce a united front in your group!"

The exchange emphasizes the different attitudes among the scientists, Gann explained.

"Watson and Crick are jovial and cavalier, even though they've just been humiliated," Gann told Livescience. "But Wilkins was always anxious and tortured about different things."

'Rosy' the scientist

The rediscovered Crick material, which includes correspondence, photographs, postcards, preprints, reprints, meeting programs, notes and newspaper cuttings, also gives new details on the relationship between Rosalind Franklin and her male colleagues.

Well-known tensions reigned early on. An early misunderstanding poisoned the relationship between Wilkins and Franklin, and Watson's rather chauvinist attitude toward Franklin at the time included complaints that she failed to wear lipstick or pretty herself up like other women.

Franklin's male peers also persisted in calling her "Rosy" or "Rosie," a nickname she disliked immensely.

Still, her work with X-ray crystallography created a certain "Photograph 51," which allowed Crick and Watson to realize that DNA has a double-helix structure. Without Franklin knowing, Wilkins showed her photograph to Crick and Watson in 1953.

Wilkins later complained to Crick and Watson in a rediscovered letter: "To think that Rosie had all the 3D data for 9 months & wouldn’t fit a helix to it and there was I taking her word for it that the data was anti-helical. Christ."

The rival labs eventually agreed to publish several papers together on the DNA structure in the journal Nature.

A twist of discovery

Many have argued that Franklin deserved Nobel recognition, because her experimental work revealed the double-helix structure that helped Crick and Watson build their DNA model. Even Watson suggested much later that Franklin and Wilkins should have shared a Nobel Prize in chemistry for their contributions.

Franklin, who had all the photographic evidence of DNA's double-helix structure in front of her, had dismissed the idea of a helix. That's because she focused her attention on the clearer data from the A form of DNA, which looks less obviously like a helix than the B form of DNA.

The crucial photograph shown to Crick and Watson had contained the B form of DNA, and so the pair immediately seized upon its helical shape. But a newly rediscovered letter shows that even they might have hesitated for a moment upon seeing the A form of DNA.

"This is the first time I have had an opportunity for a detailed study of the picture of Structure A, and I must say I am glad I didn’t see it earlier, as it would have worried me considerably," Crick told Wilkins in the summer of 1953.

Gann suspects today that Crick and Watson would have gone ahead with their double-helix model and ignored the more ambiguous evidence from the A form of DNA.

"It wasn't anti-helical; it just wasn't obviously helical," Gann said in a phone interview.

Publishing what-ifs

Other rediscovered letters include one in 1963 from C.P. Snow, the British physicist who bemoaned the communication gap between science and the humanities in a lecture titled "The Two Cultures." Snow wanted Crick to write something for general audiences about the DNA discovery story.

But Crick declined by noting he would have to consult Watson, Wilkins and everyone else involved. Five years later, Watson published his famous first-person account on his own, titled "The Double Helix."

Similarly, Crick spent six years putting off writing a textbook on molecular biology, despite pleas from a publisher. Watson eventually published a textbook called "Molecular Biology of the Gene," which defined the field of molecular biology and is now in its sixth edition.

Had Crick gone ahead and written his textbook, he might have ended up defining molecular biology in the same way, but in a different style, Gann said.

"Watson's first response when we showed him [the correspondence] was 'Wow, if he had written that I would have never written mine,'" Gann recalled.

Gann and Jan Witkowski, executive director of the Banbury Center in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, commented on the new Crick material in the Sept. 30 issue of the journal Nature.