Ancient Mayan Rituals Revealed by Ordinary Objects

Ancient Mayans farmers, builders and servants left records of their daily lives with the objects they embedded in the floors and walls of their homes during rituals in which their houses were burned down and then rebuilt, giving archaeologists today a window into everyday Mayan life.

Many of the more famous records of the Mayan civilization come from the writing and images about royals carved into monuments.

"But the commoners had their own way of recording their own history, not only their history as a family, but also their place in the cosmos," said Lisa Lucero, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois who led a new study of objects embedded in the floors of Mayan homes occupied more than 1,000 years ago in central Belize.

Even though the records differed between the classes, the buried artifacts Lucero found support an idea that many of the elaborate rituals performed by Maya rulers and elites had a basis in the domestic rituals of their subjects. The elite versions were just scaled-up.

Termination and rebuilding

In the Classic Maya period (from about the year 250 to 900), commoners regularly "terminated" their homes, razing the walls, burning the floors and placing artifacts and occasionally human remains on top before burning them again. These practices were rituals of rebirth and renewal that correspond with the cyclical view of life and nature that the Maya, and many other ancient Mesoamerican cultures, held, said Astrid Runggaldier, a visiting professor at the University of Illinois who took part in the study.

After the termination of their abode, a Mayan family would build a new home on top of the old foundation, using broken and whole vessels, colorful fragments, animal bones and rocks to mark important areas and serve as ballast for a new plaster floor.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These things are buried, not to be seen, but it doesn't mean people forgot about them," Lucero said. "They are burying people in the exact same spot and removing bones from earlier ancestors to place them somewhere else, or removing pieces of them and keeping the pieces as mementos."

Evidence suggests that these "de-animation" and reanimation rituals (so-called because the Maya imbued all objects, living or not, with living qualities and a soul) occurred around every 40 to 50 years, likely coinciding with important dates in the Mayan calendar.

Anthropologists have known about these termination rituals for decades, but Lucero looked more closely at how the arrangement, color and condition of buried artifacts lent them their symbolic meaning.

Red and rebirth

Lucero and her crew found about a dozen human remains and other objects in two homes they excavated in a small Maya center called Saturday Creek in central Belize. The homes were occupied from about 450 to 1150.

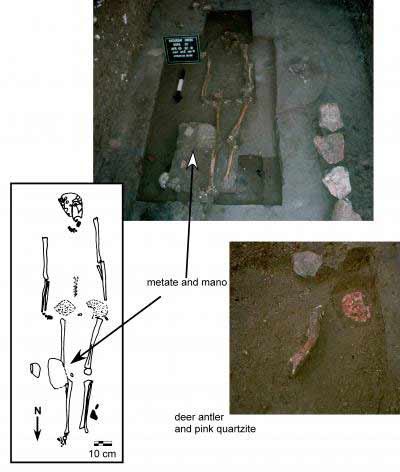

The team found partial skeletons of men, women and children, with artifacts arranged around and even on top of the bodies.

Colors, such as red, which represented the east, life and rebirth, were commonly used in these burials. Sometimes an unbroken red vessel was inverted over a skull or kneecap. Red items were generally found on the east side of the body or group of artifacts. The use of this color, instead of black, more associated with death, could be a reflection on how the Maya viewed death.

"The Maya believed in a cyclical way of living," Lucero said. "So to their way of thinking, people don't die as much as become ancestors."

Other artifacts — including groups of obsidian or chert rocks — represented the Maya belief in the nine levels of the underworld or the 13 levels of heaven.

Vessels were a significant part of dedication rites, and Lucero found bowls and jars that were in perfect condition when they were buried, suggesting they were crafted specifically for the occasion.

The team also found vessels used in termination rites that had their rims broken off or damaged with a "kill hole" drilled through their bottoms. Lucero also found jars without bases or necks and vessels stacked in groups of three, along with bowls placed lip-to-lip with stores of organic matter (possibly a food offering) inside them.

"Things that were used in life had to be de-animated, terminated, before they entered the next stage of their life history," Lucero said. Pieces of broken vessels were likely given away or placed in other sacred sites, she added.

Lucero suggested that perhaps the Maya revered the fragments of vessels or the bones of their ancestors in the same way that people today cherish religious relics, and in the same way that the Maya rulers and elite did so.

In her 2006 book, "Water and Ritual: The Rise and Fall of Classic Maya Rulers" (University of Texas Press, Austin, 2006), Lucero argues that rulers reinforced community cohesion, as well as their own high status, by adopting traditional domestic rituals and transferring them to a grand scale.

"Nearly everything royal emerged or developed or evolved from domestic practices," Lucero said. "So it makes sense to turn that around and use what we know about the rulers to interpret what we find in the commoners' homes."

- Top 10 Ancient Capitals

- Images: The Seven Ancient Wonders of the World

- Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal with the Dead

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality