Brain Breakthrough: Scientists Know What You'll Do

New research into how the brain controls movement reveals a location of thoughts that determine what you will do.

Don't worry, the scientists can't read your most fantastic or lurid imaginings. What the Caltech researchers can do is spot the flicker of activity that occurs while you contemplate moving your hand.

The research is expected to improve efforts to build neural prostheses, devices that link a paralyzed person's mind to an external device with the help of brain electrodes and a computer.

Several research programs are making progress on similar aspects of mind control over movement. Patients have shown the ability to move a cursor on a screen with nothing but brainpower, for example. And a monkey has been trained to feed itself with a robotic arm.

But the new study, announced this week, predicted where a patient would move his hand based on brain activity the instant prior. It promises a more effective way to convert desire into movement for paralyzed patients.

The research is reported in the online version of the journal Nature Neuroscience.

"Just the fact that these spatial signals are there is important," said Daniel Rizzuto, a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech who worked on the study. "Based upon previous work in monkeys, people were saying this was not the case."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research was led by Richard Andersen, a neuroscientist at Caltech, known formally as the California Institute of Technology.

Planning central

The planning of movement occurs in the brain's ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vPF), the scientists found.

The study subjects were epilepsy patients, who were already being analyzed with implanted electrodes in an effort to determine where in the brain their seizures occur.

"So for a couple of weeks these patients are lying there, bored, waiting for a seizure," Rizzuto said, "and I was able to get their permission to do my study, taking advantage of the electrodes that were already there."

The patients watched a computer screen for a flashing target, remembered the target's location, and then reached to that location.

Anderson and Rizzuto believe the planning areas of the brain are less susceptible to damage than the regions that actually initiate movement. With spinal cord injuries, for example, communication to and from the primary motor cortex is cut off, Rizzuto said. But the brain continues to plan.

By tapping into these plans, the goal of generating movement becomes just an engineering problem involving a computer and a robotic arm, the scientists figure.

"The next project that we are currently undertaking is to place paralyzed patients into an MRI scanner to record their brain activity while they imagine making arm movements," he told LiveScience. "By analyzing the brain activation of paralyzed patients compared with normal subjects we can get an indication of which brain areas reorganize after paralysis."

Multitasking

In the recent tests, there is a computer processing time lag of less than a second that Rizzuto says should not be a problem.

"If you are hooked up to a neural prosthetic and we predict that you are thinking of reaching to the coffee cup in front of you, then the best path to reach that goal can be automatically computed by an expert computer system that then controls the trajectory of the arm," Rizzuto told LiveScience. "This also allows you to do other things while the arm is moving, rather than focusing upon the trajectory of the arm the whole time."

Eventually the research will lead to human tests to see whether the planning can in fact be converted to movement.

"After this we hope to implant paralyzed patients with electrodes so that they may better communicate with others and control their environment," Rizzuto said.

Rizzuto predicts FDA approval for the first neural prosthetic device could come in five to eight years. He and others will discuss their work Sunday, March 20 at 10 p.m. ET (7 p.m. PT) on a SETI Institute talk program carried live on the Internet.

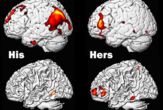

Men and Women Really Do Think Differently

Mind Control of External Devices

Ancient Behaviors Hard-Wired in Human Brain

Your Brain Works Like the Internet

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.