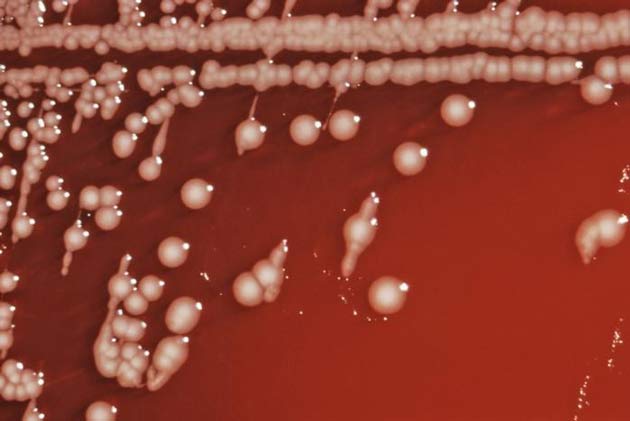

Bacteria vs. Bacteria: The New Fight Against Salmonella

Salmonella and other potentially deadly bacteria in poultry face a new enemy, as scientists develop more effective ways to fight fire with fire.

As they've been doing since the 1970s, researchers put "good" bacteria into the chickens on purpose to fight bad bacteria. Now one group has cooked up a culture of the beneficial variety that preliminary studies show is more effective in combating salmonella.

The good bacteria is sprayed on chicks or introduced into their water.

It's all okay with the Food and Drug Administration, so long as the bacteria is what researchers call a "defined culture," one that's derived from a single defined group of known bacteria.

"They're known organisms, specific isolates that are well characterized," explained Billy Hargis University of Arkansas's Food Safety Consortium project.

Yogurt science

Work in the United States and in other countries over the past three decades has led to undefined cultures of good bacteria, which contain strains that aren't identified. Researchers here worry that those cultures could contain emerging pathogens that would only make matters worse, so use is sometimes restricted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new cocktail of good bacteria—including things like enterobacteriaceae and lactic acid bacteria—is what's known as a probiotic culture. Probiotic bacteria have also been found effective in fighting human diseases. Yogurt is the classic probiotic food item, and the bacteria are available in dietary supplements, too.

The good bacteria work by exclusion—they get into the intestinal track of the bird and set up shop, leaving no room for the bad bacteria. The probiotic is given to newly hatched chicks so it can go to work before the bad bacteria take hold.

"The newly hatched chick's gut is essentially sterile and highly susceptible to pathogen colonization, whereas the mature bird can be resilient to pathogen colonization," explained Annie Donoghue of the Poultry Science Center at the University of Arkansas. "The biggest challenge is determining the correct types and quantity of probiotics because of the numbers and diversity of microbes and the poorly understood interactions between the microbes and the intestine."

You don't want this

Salmonella infection causes diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramps for up to seven days and in extreme cases can be deadly. Some 40,000 cases are reported each year in the United States, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that perhaps 30 times that many mild cases go unreported. About 600 people die from it each year.

Thorough cooking kills the bacteria, but they can be introduced to raw vegetables or cooked food if a cook does not wash his hands after using the restroom.

Hargis and colleagues think their approach will help, however.

"Salmonella does not occur by spontaneous generation in a processing plant," he said. "It comes in with the live animals. I think it's a pretty good bet that reducing salmonella in live animals will end up reducing salmonella in food."

Much of the research is being done at a handful of labs around the country, which like Hargis' are supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Hargis said several companies have begun using the new product.

"Our cultures are different because they can be truly defined and they can be reproduced from specific isolates that are stored back in the freezer," Hargis said. "Then they can be propagated virtually forever."

And are they safe for humans?

"These are all considered GRAS organisms—Generally Recognized As Safe," Donoghue said in an email interview. "These are similar to the bacteria found in yogurts."

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

La Crosse virus disease: The rare mosquito-borne illness that causes deadly brain inflammation

Parasitic worm raises risk of cervical cancer, study finds