Is the Red Sea really red?

The Red Sea acquired its name from blooms produced by abundant algae.

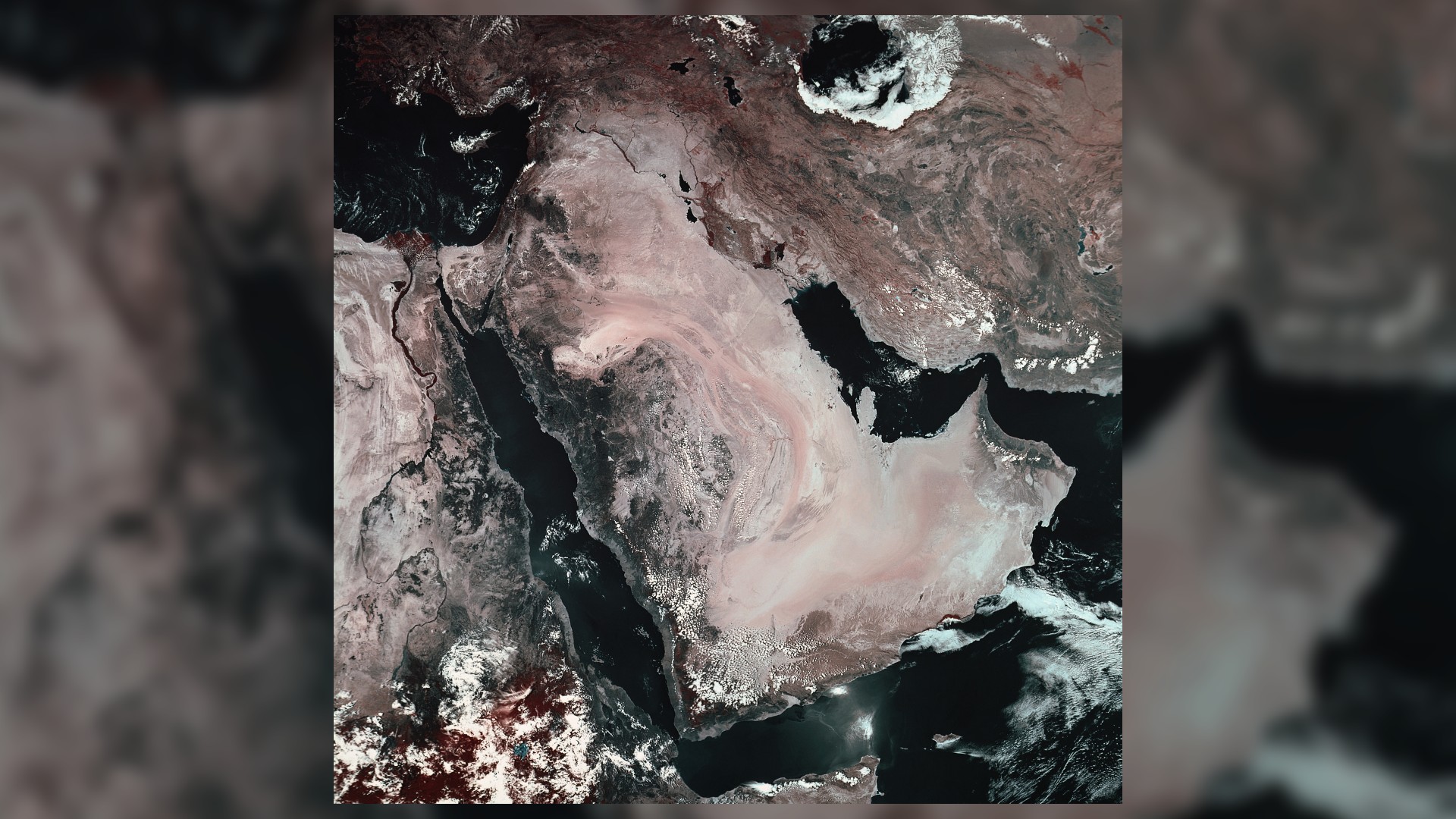

Satellite images taken from space show the Red Sea as a blue line running roughly from north to south along the northeastern edge of the African continent. The intense blueness of the water, which stands in stark contrast to the drab brown of the surrounding landscape, belies the sea's famous name. There's seemingly nothing "red" about the Red Sea.

So, how did the Red Sea acquire its famous moniker?

"I don't think anyone knows for sure how it got its name," said Karine Kleinhaus, an associate professor of marine and atmospheric sciences at Stony Brook University in New York. But it's possible, she added, that the answer might have to do with algae — in this case, Trichodesmium erythraeum. Sometimes called "sea sawdust," it is a type of cyanobacteria (aquatic bacteria that survive through photosynthesis) that belongs to the blue-green algae group, and it is responsible for between 60% and 80% of nitrogen conversion in the ocean, according to NASA Earth Observatory.

Related: Why are there so many giants in the deep sea?

T. erythraeum is prolific and is found in much of the world's tropical and subtropical oceans. It grows abundantly in the Red Sea and is subject to periodic blooms, which occur when there is a rapid growth of the population. When the algae die off, the water takes on a reddish-brown color as the dying algae spread across the sea's surface.

However, it's also possible that the Red Sea is named after the red mountains that line parts of its shoreline, such as along the Jordanian coast, Kleinhaus said.

But the Red Sea isn't defined solely by its name. "The Red Sea is a hotspot of biodiversity with many endemic animals that are found only in the Red Sea or the Gulf of Aden," Kleinhaus said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Long and narrow, the Red Sea [in Arabic, Al-Bahr Al-Ahmar] is sandwiched between northeast Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. It extends approximately 1,200 miles (1,930 kilometers) from the Gulf of Suez in the north to the Gulf of Aden in the south, eventually connecting with the Indian Ocean. According to Britannica, the Red Sea's maximum width is 190 miles (305 km) and its maximum depth is 9,974 feet (3,040 meters). It covers an area of approximately 174,000 square miles (450,000 square km).

The Red Sea has one of the world's longest continuous coral reefs. It extends for 2,485 miles (4,000 km) and hosts a rich diversity of marine life. The reef's unique characteristics make it one of the world's only marine refuges from climate change, Kleinhaus said.

"The corals that reached there at the end of the last ice age were only those that could tolerate very high temperatures and salinity, because of the conditions of the Red Sea at the time they entered," Kleinhaus said. "Therefore, they are now living well below their maximum temperatures and are predicted to be one of the last coral reefs to survive this century."

The Red Sea is one of the world's youngest bodies of water and was formed by the splitting of two tectonic plates, the Arabian Plate and the African Plate, said Kleinhaus. "These are still drifting apart, so it is a growing sea," she added.

Additional resources

- Watch a video about the Red Sea on the Documentary Central on YouTube.

- Read about the geological history and evolution of the Red Sea in an excerpt from the Springer Earth System Sciences book series.

- Learn some facts about the Red Sea from World Atlas.

Bibliography

NASA Earth Observatory, (2019) "A Bloom of Nitrogen-Fixing bacteria." https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/145610/a-bloom-of-nitrogen-fixing-bacteria

Britannica, "Red Sea." https://www.britannica.com/place/Red-Sea

Originally published on Live Science on Sept. 12, 2012 and rewritten on June 8, 2022.

Tom Garlinghouse is a journalist specializing in general science stories. He has a Ph.D. in archaeology from the University of California, Davis, and was a practicing archaeologist prior to receiving his MA in science journalism from the University of California, Santa Cruz. His work has appeared in an eclectic array of print and online publications, including the Monterey Herald, the San Jose Mercury News, History Today, Sapiens.org, Science.com, Current World Archaeology and many others. He is also a novelist whose first novel Mind Fields, was recently published by Open-Books.com.