Hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones: Earth's tropical windstorms

These whirling windstorms are one of Mother Nature's most destructive natural disasters.

If you live or like to vacation along the world's coastlines, chances are good you've been affected by a tropical storm or hurricane.

Hurricanes, which are more broadly called "tropical cyclones" because they originate over Earth's tropical oceans, are some of nature's largest and fiercest storms. They get their name from Hurican, the Carib god of evil, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Worldly windstorms

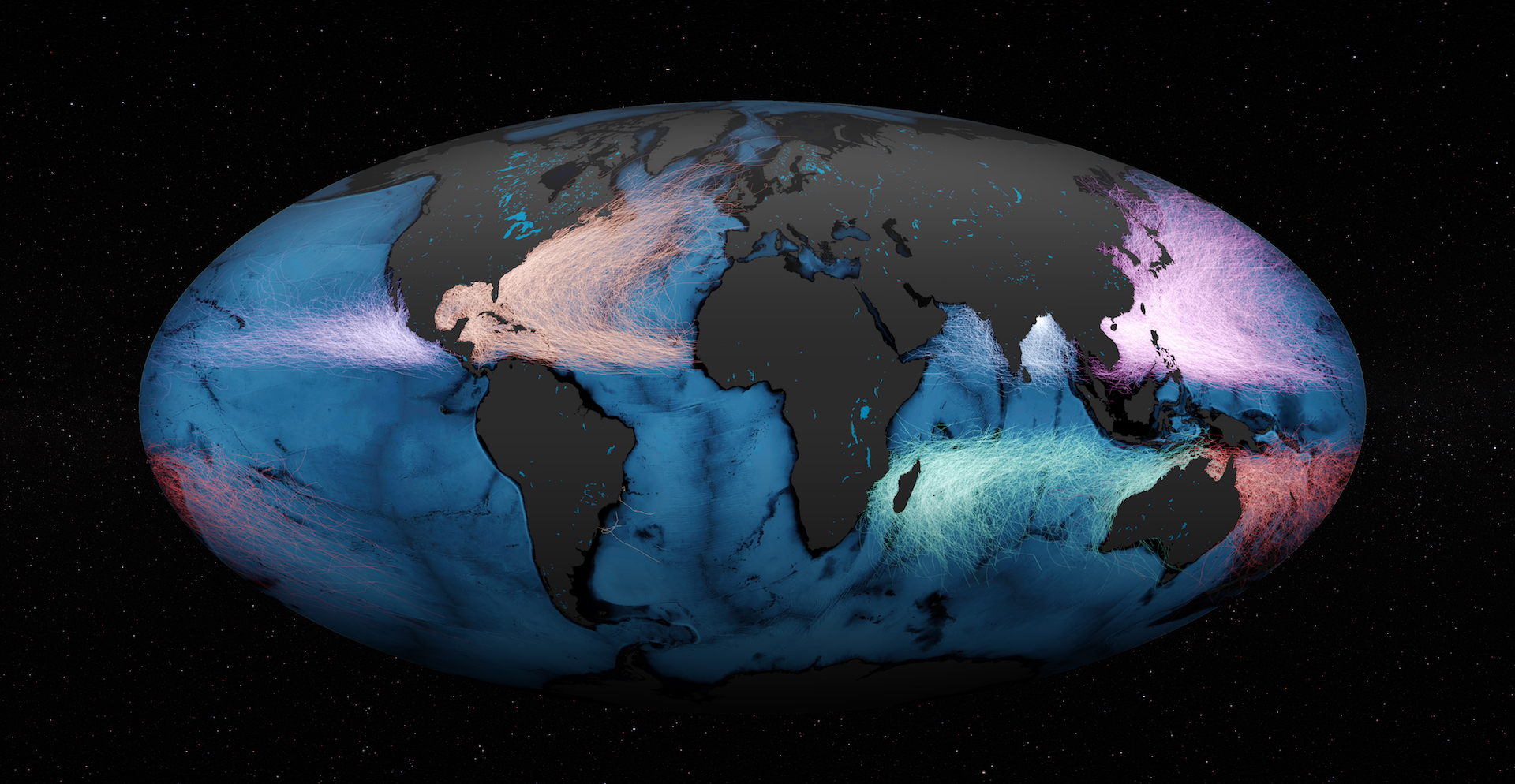

Tropical cyclones form in most of the world's tropical oceans, but always at least 300 miles (480 kilometers) north or south of the equator. Any closer to the equator than this, and the inertial force that causes storms to spin to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere, called the coriolis force, won't cause the storm system to spin.

When they form in the Atlantic or Eastern Pacific Oceans, tropical cyclones are called hurricanes. In the western North Pacific, the same type of storms are called typhoons. And in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, they are called cyclones.

The Atlantic hurricane season lasts from June through November. The Eastern Pacific hurricane season runs from mid-May through November. Typhoons in the North Pacific occur year-round but peak in late August. And in the South Pacific, the cyclone season begins in October and ends in May.

In the Atlantic, hurricanes typically follow one of three paths, according to NOAA's National Hurricane Center:

- Originating off the West Coast of Africa near the Cape Verde Islands and traveling west toward the Caribbean and the East Coast of the United States.

- Originating in the western Caribbean, and moving into the U.S. Gulf Coast, or along the U.S. East Coast.

- Originating in the Gulf of Mexico and crashing into the Gulf Coast states, anywhere between Texas and Florida.

How hurricanes form

As with any weather event, certain atmospheric ingredients must be in place for a hurricane to cook up over the open ocean. According to NOAA's National Weather Service, these include:

- Warm ocean waters of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27 Celsius) extending from the sea surface to a depth of 150 feet (46 meters) underwater.

- A moist and unstable atmosphere. In other words, an atmosphere with high humidity at upper levels and one in which air has a tendency to rise.

- A pre-existing disturbance near surface levels, such as a complex of thunderstorms, which meteorologists call tropical easterly waves.

- Sufficient distance (at least 300 miles, or 480 km) from the equator.

- Little to no wind shear, meaning wind speed and direction varies little between the surface and the troposphere, the lowest level of Earth's atmosphere, which stretches tens of thousands of feet above the surface.

When a storm forms under these minimum criteria, it is deemed a tropical cyclone, or more specifically, a tropical disturbance. At this initial stage, the disturbance is essentially a cluster of marine clouds and thunderstorms, but if ocean temperatures remain sufficiently balmy, the disturbance will continue to strengthen. And as the system becomes slightly more organized it may start to circulate. When the storm system's winds begin to circulate around a well-defined center, but its maximum sustained wind speeds have not exceeded 38 mph (61 km/h), the storm becomes categorized as a "tropical depression." It's at this stage that the storm earns a name.

Related: Storm targets: Where the hurricanes hit (infographic)

Once maximum sustained winds reach between 39 and 73 mph (63 to 117 km/h), the cyclone is classified as a "tropical storm." And when a storm's sustained winds reach 74 mph (119 km/h) or greater, the cyclone is classified as a hurricane — or typhoon if it's in the North Pacific, and cyclone if in the South Pacific.

How hurricanes are categorized

Hurricanes are categorized according to the speed of their maximum sustained winds. The scale used for this purpose, called the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, was developed in 1971 by civil engineer Herbert Saffir and by meteorologist and then-director of the U.S. National Hurricane Center, Bob Simpson. The Saffir-Simpson scale rates a hurricane's severity from 1 (very dangerous) to 5 (catastrophic), based on the following wind speeds:

- Category 1: Winds of 74-95 mph (119-153 km/h)

- Category 2: Winds of 96-110 mph (154-177 km/h)

- Category 3: Winds of 111-129 mph (178-208 km/h)

- Category 4: Winds of 130-156 mph (209-251 km/h)

- Category 5: Winds exceeding 157 mph (252 km/h)

Hurricanes that reach Category 3 or higher are considered "major hurricanes" because of their potential to cause significant damage and loss of life. Similarly, typhoons with winds exceeding 150 mph (241 km/h) earn the title of "super typhoon."

Although winds are the most common way to measure how intense a tropical cyclone is, central barometric pressure, which is the air pressure exerted by Earth's atmosphere on the storm's geographical center, is another way meteorologists measure a storm's intensity. In general, the lower a storm's central pressure, the stronger the storm. While lower pressure and higher winds tend to go hand-in-hand, one isn't necessarily indicative of the other. For example, as of 2019, Hurricane Wilma (2005), a Category 5 hurricane, held the record for the lowest central pressure (882 millibars) of any Atlantic hurricane, but Hurricane Allen (1980), also a Category 5 hurricane, ranks as the Atlantic hurricane with the strongest winds (its sustained winds reached 190 mph, or 306 km/h).

Beware of these features and hazards

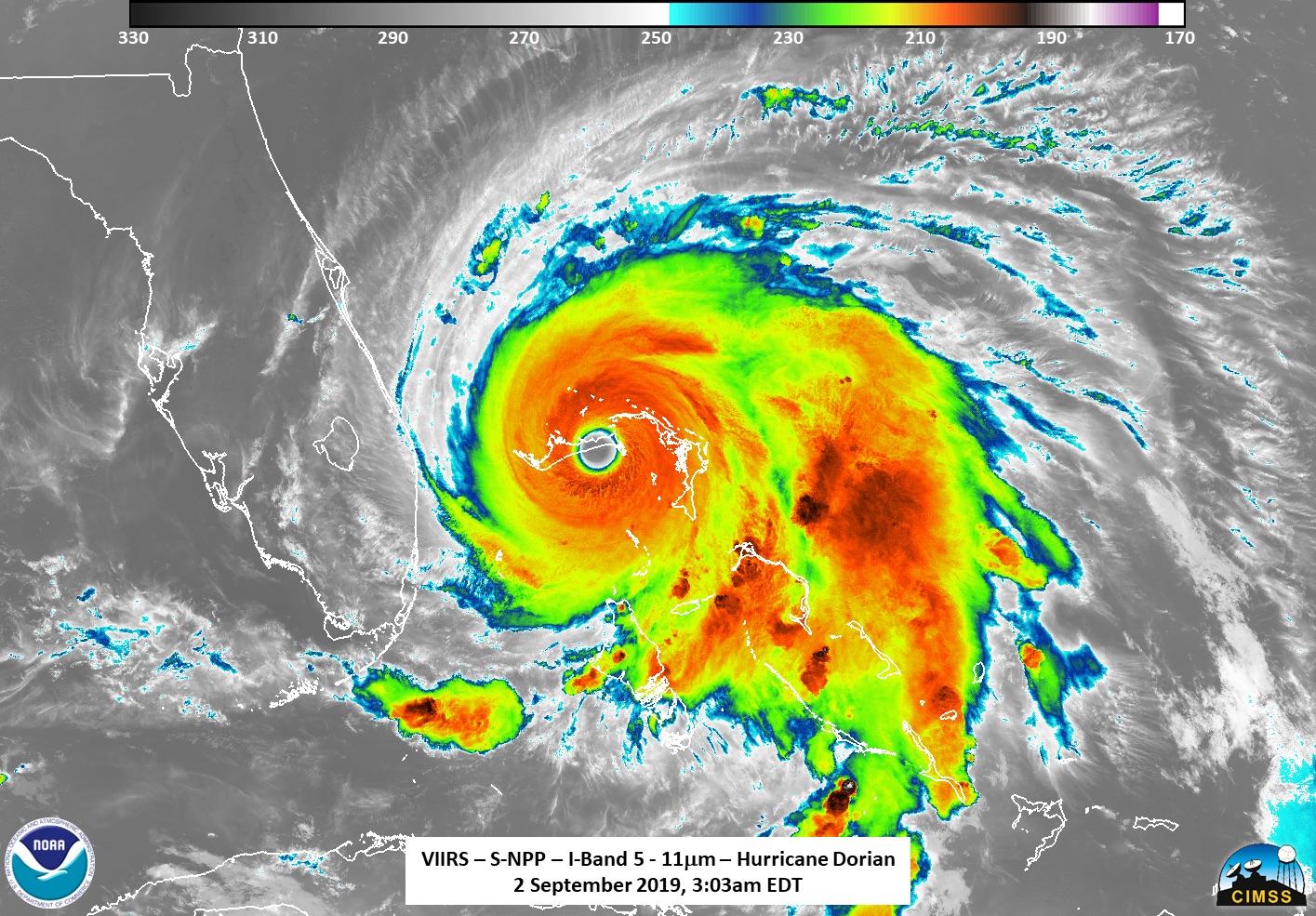

The main physical features of a hurricane are its rainbands, eye and eyewall. These features take shape as surface air from all directions spirals in toward the center of the storm in a counter-clockwise pattern (or clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere).

Because this converging air has nowhere else to go it rises, creating a column of forceful rising air at the storm's center known as the eyewall. Rising air encourages clouds and thunderstorms to develop, which is why the eyewall is surrounded by a ring of towering thunderstorms that inflict some of the cylone's most severe punishment. Curved bands of clouds and thunderstorms trail away from the eyewall in a spiral fashion. These rainbands, which typically extend outward 50 to 300 miles (80 to 483 km) from the cyclone's center, can produce heavy bursts of rain and wind, as well as tornadoes.

Related: Hurricane preparation: What to do

The eyewall's strong rotation of air creates an empty vortex at its center. This empty area is the eye of the storm, and spans a distance about 20 to 40 miles (32 to 64 km) in diameter on average, according to NOAA. Inside the eye, air from the top of the cyclone sinks back down toward the surface to fill the void of the air that was pulled into the storm. Sinking air inhibits cloud formation, which is why the eye has calm winds and clear skies. A tropical cyclone is said to have made landfall when its eye hits the shoreline.

Violent winds are not the only hazard of hurricanes or cyclones. Storm surges — walls of seawater that are pushed toward shore by the sheer force of a storm's winds — can increase water levels by 15 feet (4.5 m) or more above the predicted astronomical tide. In 2017, the National Weather Service began issuing storm surge watches and warnings to alert areas along the U.S. Gulf and Atlantic coasts of the unique risk for life-threatening inundation from approaching tropical cyclones.

Flooding caused by storm surges and by heavy rainfall is a major hazard of hurricanes. According to a 2014 study published in The Bulletin of the American Meteorology Society, storm surge flooding has been the leading cause of hurricane-related fatalities for the past 50 years.

Related: The costliest hurricanes in history

Who picks hurricane names?

Hurricane names are determined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, that serves as the international authority on weather, climate and hydrology. The WMO maintains six lists of alphabetical names that are recycled and reused every six years for the Atlantic and eastern Pacific Ocean basins. It also composes separate lists for the globe's five other cyclone zones, including the western Pacific, northern Indian, southwestern Indian, southeastern Indian, and Australian Ocean basins.

According to the National Hurricane Center, the current practice of assigning male and female names to hurricanes wasn't put into place until 1979. Before this, only female names were used. And for hundreds of years before that, storms often took the name of the holiday or saint's day on which they occurred.

Names are preferred to numbers because they're easier to remember. The one exception to this no-numbering rule is tropical depressions; because they aren't named, they take the title of whatever number cyclone they are within a particular season-year, that is, "Tropical Depression Three," or "Tropical Depression Fifteen," etc.

If a storm is ever so deadly or destructive that the future use of its name would be insensitive, that name is retired and a replacement name is chosen. For example, the names Katrina and Sandy have been removed from the list of Atlantic cyclone names because of the astounding amount of destruction and death that resulted from Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Sandy (2012). More recently, Matthew (2016), Maria (2017), Florence (2018), and Michael (2018) were retired.

During extremely busy Atlantic hurricane seasons, all the names on the names list may be used up. When this happens, subsequent storms receive a name from the Greek alphabet (Alpha, Beta, Gamma and so on). This has only ever happened twice, according to NOAA: in 2005 and again in 2020.

Hurricanes and climate change

Hurricanes feed off of heat energy, so as Earth's global temperatures continue to rise, hurricanes are bound to be affected. So far, it's not evident that hurricanes are necessarily forming more often because of rising temperatures, although scientists do predict that hurricane activity and intensity will likely increase in future years.

There is, however, a clear link between global warming and an increase in the number of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes. Climate change also appears to be causing hurricanes to intensify more rapidly than ever before, and to produce far more rain, according to Yale Climate Connections. These trends are likely a result of higher ocean temperatures and higher water vapor content in the atmosphere as the air heats up, according to NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

Warmer-than-average ocean temperatures in the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean Sea are already contributing to the active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, NOAA reported. Similar conditions have been producing busier-than-normal hurricane seasons since 1995. Scientists predict the annual trend of more frequent extreme storms and record-breaking hurricane seasons to continue as long as climate change persists.

Additional resources:

- Track active tropical cyclones at NOAA's National Hurricane Center.

- Discover which cyclone names are on this year's list at the World Meteorological Organization.

- Learn how to prepare for a hurricane at Ready.gov.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tiffany Means is a meteorologist turned science writer based in the Blue Ridge mountains of North Carolina. Her work has appeared in Yale Climate Connections, The Farmers' Almanac, and other publications. Tiffany has a bachelor's degree in atmospheric science from the University of North Carolina, Asheville, and she is earning a master's in science writing at Johns Hopkins University.