Will the Large Hadron Collider Destroy Earth?

The potential for the world's largest atom smasher to destroy Earth is one question weighing on the minds of some lay people as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) prepares to go online Wednesday.

Don't worry, say the experts, who are more concerned with whether the 17 mile-long particle accelerator underground at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research near Geneva, Switzerland, will work as planned and, perhaps, reveal the existence of the so-called God particle.

All that in mind, here are answers to several questions buzzing around on the eve of the LHC's inaugural run:

So, will a black hole consume the planet?

Some people have suggested that a microscopic black hole, spawned by the powerful crash of subatomic particles racing through the LHC's tunnels, could potentially suck up the Earth.

But physicists say these fears are unfounded. For one, creating a black hole at LHC is extremely unlikely based on the laws of gravity alone, CERN officials say. But even if it did happen, as a few highly speculative theories suggest, the miniscule black hole would be so unstable it would disintegrate immediately before it had time to gobble up any of the matter on Earth.

Will a 'strangelet' destroy us?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another wild idea: The LHC might produce something called a strangelet that could convert our planet into a lump of dead "strange matter."

This hypothesis is equally unlikely, experts say, because the same worries were raised eight years ago before the opening of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a particle accelerator at the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island. Since RHIC has been operating safely for years, and it's set-up made it even more likely to produce strangelets if such creation were possible, then the LHC poses little risk of converting us into strangelings.

Although worrywarts have gone so far as to file suit in Federal District Court in Hawaii and in the European Court of Human Rights to stop the LHC (as they also did before RHIC), the project will go ahead as planned.

"The LHC will enable us to study in detail what nature is doing all around us," said CERN Director General Robert Aymar. "The LHC is safe, and any suggestion that it might present a risk is pure fiction."

Just how big is this thing?

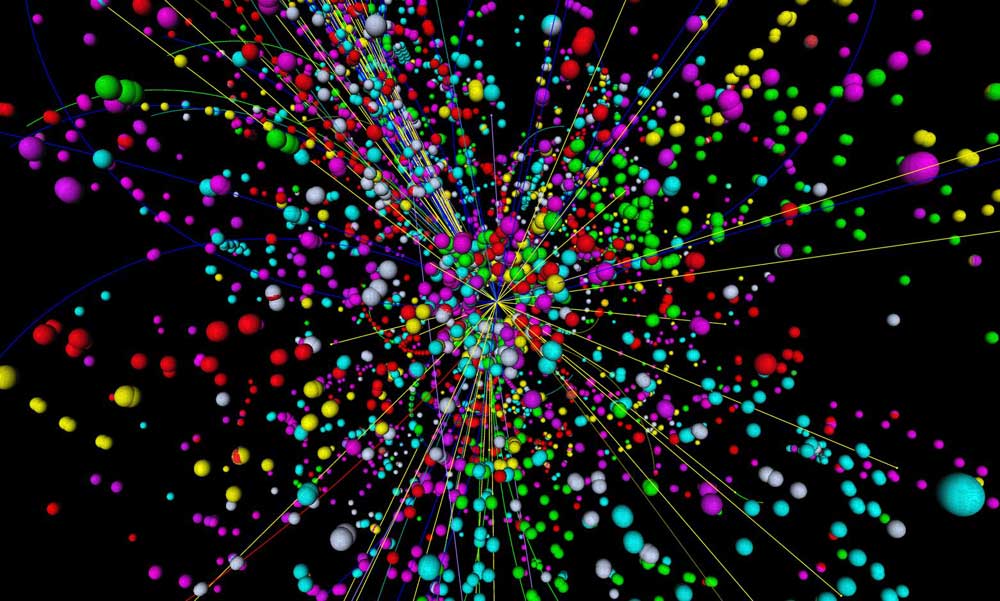

The LHC is an underground ring about 17 miles (27 kilometers) long, running through parts of both Switzerland and France. Inside are 9,300 magnets guiding two beams of particles around the circle in opposite directions until they smash into each other, spewing out loads of energy and hopefully some new and exciting particles.

How fast will the particles go?

The speeding particles will travel the full LHC ring 11,245 times a second, travelling at 99.99 percent the speed of light. At this rate, some 600 million collisions will take place every second.

Don't we already have a bunch of atom smashers? What's so special about this one?

The LHC will be the mother of all atom smashers: the largest, the most powerful, with the biggest and most sophisticated detectors ever built. Although there are a number of particle accelerators around the world, each was built for a unique purpose. Scientists are hoping the LHC will be able to answer some of our most puzzling outstanding questions about the nature of the universe, including how stuff gets mass, what makes up dark matter, and why the universe is made up of matter and not anti-matter.

How much does it cost?

The facility cost $8 billion, $531 million of which was contributed by the United States. More than 8,000 scientists from almost 60 countries will collaborate on LHC experiments.

How long have they been working on this?

The green light for the project was given 14 years ago, though some physicists have been planning the LHC since the 1980s.

Why does it have to be underground?

The planet shields the accelerator from radiation that could interfere with the experiments. Not to mention buying that much land aboveground would have been really expensive!

By the way, what's a hadron?

Hadrons are particles made up of bound quarks. A quark is a building block of larger particles such as protons and neutrons. The LHC will manipulate two kinds of hadrons — either protons or lead ions — because a) they are charged (this allows them to be accelerated by the electromagnetic forces created in the machine) and b) they do not decay and are heavy so they will not lose too much energy as they are accelerated along the ring.

And what's a 'God particle'?

The God particle is the nickname given to the theoretical Higgs boson, a particle thought to explain why some things are more massive than others. The Higgs is one of the holy grails of physics, though its existence has yet to be proven.

Will the LHC find the God particle?

While many are hoping that Higgs bosons will pop out of the powerful collisions created by the LHC, the famous British astrophysicist Stephen Hawking is betting it won't. He's wagered $100 (70 euros) that LHC won't produce the elusive God particle and physicists will have to go back to the drawing board.

"I think it will be much more exciting if we don't find the Higgs," Hawking told BBC radio. "That will show something is wrong, and we need to think again."

Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.