Woman Gets Parasitic Worms in Her Eyes After a Trail Run

Normally, this worm infects only cows.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A trail run near the California coast may have led a woman to contract a horrifying infection with a rare parasitic eye worm.

The woman is only the second person known to have contracted this particular worm, which typically infects cows, according to a new report of the case, published Oct. 22 in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The 68-year-old woman lives in Nebraska but spends her winters in California in an area called Carmel Valley. The inland valley located about 13 miles (21 kilometers) from the coast is known for its wineries and hiking trails.

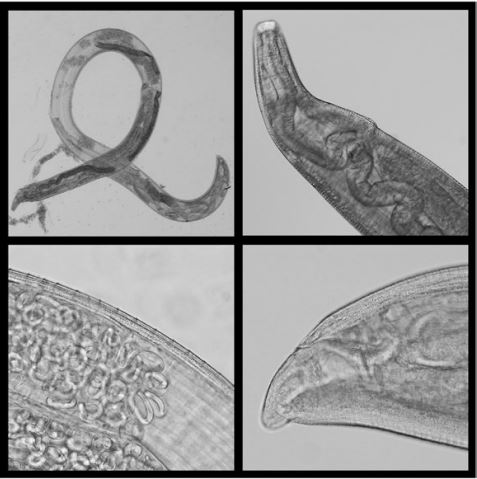

She was there in March 2018 when she felt irritation in her right eye and so flushed the eye with tap water. That's when a 0.5-inch (1.3 centimeters), wriggly roundworm came out. After this discovery, she looked more closely at her eye and saw a second roundworm, which she also removed, the report said.

Related: 27 Oddest Medical Case Reports

The next day, the woman went straight to an eye doctor in Monterey, California, who retrieved a third roundworm (also known as a nematode) from the woman's eye and preserved the worm in formaldehyde. The doctor told the woman to continue to flush her eye with distilled water to remove any more worms. She was given a topical medication to prevent any bacterial infections from taking hold.

The preserved worm sample was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where researchers determined that the woman was infected with a species of eye worm called Thelazia gulosa. Only one other human case of T. gulosa has ever been reported, in a 26-year-old Oregon woman who became infected in August 2016, Live Science previously reported. The worm usually infects cattle and is carried by certain types of face flies that consume eye secretions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Doctors don't know for sure how the Nebraska woman got the infection. But she told doctors that she is a trail runner. She added that she distinctly remembers a particular run in Carmel Valley in February 2018 during which she rounded the corner of a steep trail and ran into a swarm of flies, the report said. She remembered "swatting the flies from her face and spitting them out of her mouth," the report said, and this may have been the moment she was infected.

After going to the Monterey doctor, the woman soon returned to Nebraska, but she still felt like there was something in her eyes. Although several doctors in her home state failed to see any more worms, the woman eventually pulled a fourth worm from her eye, the report said.

The standard treatment for worms like these is to simply remove them, although in some cases, doctors use an anti-parasitic drug called ivermectin to treat eye worms. In the woman's case, treatment with ivermectin was considered but postponed. Instead, the woman irrigated her eyes for two more weeks. After that, her eye irritation went away and no more worms were found, the report said.

Having a second human case of T. gulosa occur within two years of the first case "suggest[s] that this may represent an emerging zoonotic disease in the United States," the authors of the case study wrote. (A zoonotic disease is one that jumps from animals to people.)

This species of eye worm has been known to infect cows in North American since the 1940s, but it remains unclear why doctors are only now seeing human cases, the report said.

It may be that T. gulosa infections are becoming more common in domestic cows, resulting in "spillover" events in humans, the authors wrote. However, there's no way to officially track T. gulosa cases in cows, so researchers don't know if the infection rate is really increasing.

The authors also note that, in the particular worm they examined from the Nebraska case, they saw eggs developing, "indicating that humans are suitable hosts for the reproduction of T. gulosa," they wrote.

The researchers recommended that future studies survey cattle for cases of T. gulosa, keeping track of where they are occurring. This data would suggest which regions of the U.S. are more likely to see human infections. Doctors should also continue to look out for human cases of T. gulosa.

- 10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species

- 27 Devastating Infectious Diseases

- 10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus