A puzzlingly regular waxing and waning of Earth's biodiversity may ultimately trace back to our solar system's bobbing path around the Milky Way, a new study suggests.

Every 60 million years or so, two things happen, roughly in synch: The solar system peeks its head to the north of the average plane of our galaxy's disk, and the richness of life on Earth dips noticeably.

Researchers had hypothesized that the former process drives the latter, via an increased exposure to high-energy subatomic particles called cosmic rays coming from intergalactic space. That radiation might be helping to kill off large swaths of the creatures on Earth, scientists say.

The new study lends credence to that idea, putting some hard numbers on possible radiation exposures for the first time. When the solar system pops its head out, radiation doses at the Earth's surface shoot up, perhaps by a factor of 24, researchers found.

"Even with the lowest assumption, this exposure provides a real stress on the biosphere periodically," said lead author Dimitra Atri of the University of Kansas, who presented the findings last week at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Dangerous cosmic rays

Cosmic rays are primarily high-energy protons that are spawned by supernova shock waves and other dramatic events throughout the universe. They're constantly flooding Earth, hitting every square inch of our planet's upper atmosphere several times per second.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But cosmic rays don't make it all the way to the ground. Instead, they slam into various atoms in the atmosphere, generating a cascade of lower-energy particles, such as muons.

"It's kind of a particle shower," Atri told SPACE.com.

Thousands of muons pass through our bodies every minute. Though these particles can ionize molecules by knocking out spare electrons, potentially damaging DNA, humans and other lifeforms can deal with this normal, background radiation.

"Life has evolved with this kind of radiation dose," Atri said.

But what may be able to knock life for a loop, Atri added, are spikes in the radiation dose. Such massive increases could come from an occasional event, such as a nearby supernova explosion. Or they may result if Earth loses some of its protective shielding from time to time.

Peeking out from under the galactic shield

On the Milky Way's "northern" side, about 60 million light-years away, lies the huge Virgo Cluster of galaxies. The Virgo Cluster's powerful gravity tugs the Milky Way toward it at about 450,000 mph (720,000 kph). This mad rush creates a shock wave, which generates lots of high-energy cosmic rays on the north side of the galactic disk, researchers said.

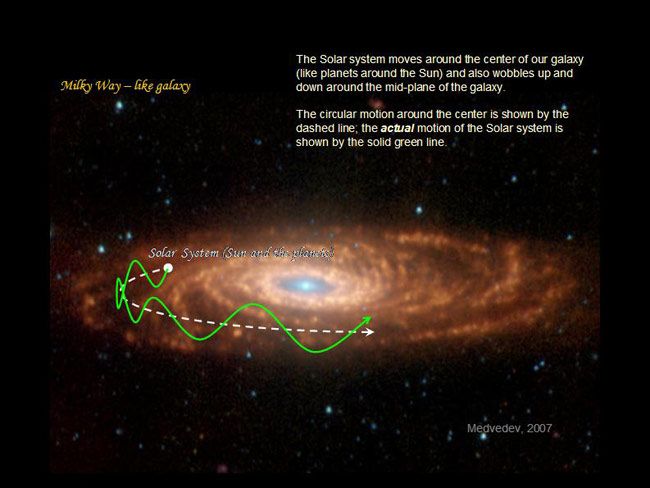

Usually, the Milky Way's magnetic field shields the solar system from most of these potentially dangerous particles. But every 64 million years or so, our solar system pops up above the northern edge of our galaxy's disk, exposing Earth to more cosmic rays, researchers said.

This periodicity matches up well with a biodiversity pattern detected by other researchers in 2005: Over the last 542 million years, the diversity of life on Earth has fluctuated regularly, with the total number of species on the planet rising and falling every 62 million years.

In 2007, researchers Mikhail Medvedev and Adrian Melott, both of the University of Kansas —Melott is Atri's graduate advisor and a co-author on the current study —proposed that the synchronicity of these two cycles is no accident.

A surge in cosmic ray exposure slashes species richness, the theory goes; biodiversity recovers, only to be cut down by the next surge 60-odd million years later.

The new study puts some numbers on that conjecture for the first time.

Modeling radiation dose

Atri and Melott modeled the radiation dose Earth receives when the solar system bobs up above the Milky Way's disk. Simulating cosmic-ray particle showers is a complicated enterprise, so the team used supercomputers at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, located at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

After chewing through many hours of supercomputer time, Atri and Melott determined a range for the radiation dose received at Earth's surface during our planet's periodic vulnerable periods. At the lower bound, Earth would receive 88 percent more radiation than normal, or about 1.88 times the average dose.

The upper end is scary: 24.5 times the background dose.

"That is just huge," Atri said.

And even radiation doses nearer to the lower bound are likely substantial enough to affect biodiversity, he added. They could stress organisms and ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to other damaging events, such as volcanic eruptions and asteroid impacts.

"Even if it's not directly causing biodiversity to go down, such a dose produces a stress on the biosphere," Atri said.

- Video: Supernova As Creator and Destroyer

- Mysterious Origin of Cosmic Rays Pinned Down

- Death Rays From Space: How Bad Are They?

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.