Far Side of the Moon Explained

The far side of the moon is forever hidden from the naked eye on Earth, but now scientists have developed a simple way to describe how it looks, and in doing so could shed light on its enigmatic history.

The simple mathematical formula they devised "explains at least a quarter of the moon's geography and geology," including the lunar far side's highlands, Ian Garrick-Bethell, a lunar scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said. [Graphic: The moon's far side explained]

The near and far sides of the moon are very different — for instance, elevations on the far side are some 1.2 miles (1.9 km) higher, on average — and understanding the roots of those differences could shed light on the mysterious earl698 Flushing Ave. #1B, Brooklyn, NY, 11206y days of the moon.

Far side of the moon

The moon always keeps the same side turned toward Earth, which means one cannot see its far side — often erroneously referred to as its "dark side" — from Earth's surface. Humanity saw its first pictures of the far side of the moon in 1959 from unmanned probes, and human eyes first directly observed it during the Apollo 8 mission in 1968.

Researchers discovered the formula while analyzing sets of lunar topography and gravity data, Garrick-Bethell told SPACE.com.

The stretch of the moon's far side surface explained by the new formula has to be the oldest lunar feature seen yet, since it lies beneath the ancient South Pole-Aitken Basin. The mathematics of it is similar to what applies to Jupiter's tidal effects on its moon Europa.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

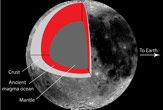

"Europa is in many ways different from the moon, but early on, the moon had a liquid ocean under its crust, and it likely shares that in common with present-day Europa," Garrick-Bethell said. "The ocean for the moon was of liquid rock, however, not water."

Moon's magma ocean

Just as the moon tugs on Earth's oceans, generating tides, so does Earth pull at the moon. The researchers suggest that roughly 4.4 billion years ago, when the moon was less than 100 million years old and its crust floated on an ocean of molten rock, these tidal effects caused distortions that were later frozen in place.

"People have been thinking about tidal explanations for the large-scale structure and shape of the moon for at least 100 years," Garrick-Bethell said. "The new thing here was to look at only one specific region of the moon that is very old, rather than to test the hypothesis over the moon as a whole, which was done previously.

"As a whole, the moon exhibits a wide range of geologic processes, some young and some old, so I don't think it's fair to explore it as a whole."

These findings yield insight into the fundamental processes that built the lunar crust, Garrick-Bethell said.

"I would like to map out how this terrain may actually extend to other parts of the moon, and encompass even more surface area than we initially report," he added.

The scientists detail their findings in tomorrow’s (Nov. 12) issue of the journal Science.

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site of Live Science.