Hellish Venus Atmosphere May Have Had Cooling Effect

It may seem downright bizarre, but a new model of Venus' super-hot atmosphere suggests its greenhouse gases may actually be cooling the planet's interior.

These gases initially cause Venus' temperature to rise, but at a certain threshold, they can trigger dynamic processes – which researchers call "mobilization" – in the planet's crust that cool the mantle and overall surface temperature, researchers found.

Venus surface temperature, on average, is a scorching 860 degrees Fahrenheit (460 degrees Celsius). [10 Extreme Planet Facts]

"For some decades we've known that the large amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of Venus cause the extreme heat we observe presently," said study leader Lena Noack of the German Aerospace Center in Berlin.

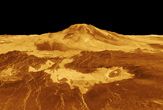

Carbon dioxide and other greenhouses gases that led to Venus' hellish temperature were belched into the planet's atmosphere over time through erupting volcanoes.

Noack and her colleagues examined the interaction of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in Venus' atmosphere and conclude that the planet may have been even hotter than it is today, Noack said.

"But at a certain point this process turned on its head – the high temperatures caused a partial mobilization of the Venusian crust, leading to an efficient cooling of the mantle, and the volcanism strongly decreased," Noack said. "This resulted in lower surface temperatures, rather comparable to today's temperature on Venus, and the mobilization of the surface stopped."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

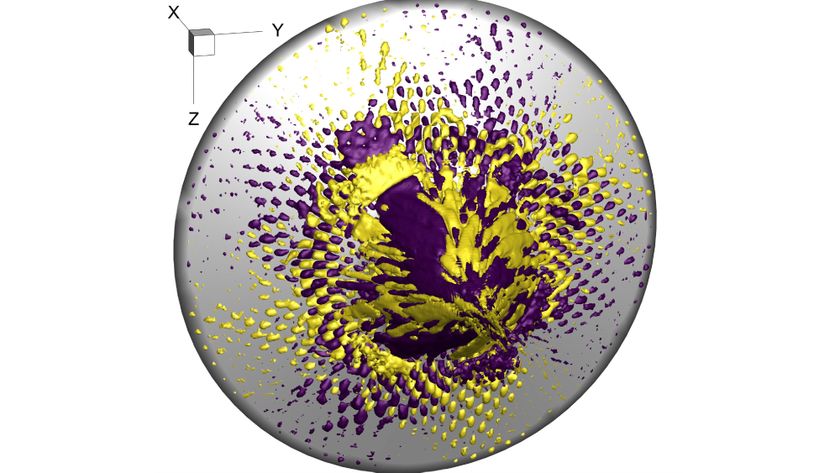

Noack and co-author Doris Breuer built a one-of-a-kind Venus computer model in which the planet's hot atmosphere was paired with a 3-D model of the interior.

Unlike on Earth, Venus’ high temperatures have a much bigger effect on the rocky surface, which ultimately loses its insulating qualities, the researchers said.

"It's a little bit like lifting the lid on the mantle: The interior of Venus suddenly cools very efficiently and the rate of volcanism ceases," Noack said. "Our model shows that after that 'hot' era of volcanism, the slow-down of volcanism leads to a strong decrease of the temperatures in the atmosphere."

Their models also suggested differences in the time and place in which the volcanoes resurfaced Venus over time.

So even as Venus' atmosphere cooled, there would remain a few active volcanoes which resurface some spots with lava flows, researchers said. In fact, some of these volcanoes might be active even today, according to recent results from the European Space Agency's Venus Express mission.

Venus Express launched in 2005 and arrived at the cloud-covered planet a year later. The spacecraft recently detected 'hot spots' on Venus, or areas of unusually high surface temperatures, at volcanoes that were previously thought to be extinct.