World's Fastest Plant: New Speed Record Set

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Like a medieval catapult, the bunchberry dogwood shoots pollen grains into the air faster than the Venus flytrap can snap its jaws shut, giving this launcher the speed record for plants.

"Most people think of plants as stationary and sedentary," said Joan Edwards of Williams College. "We were even surprised how fast this flower opens."

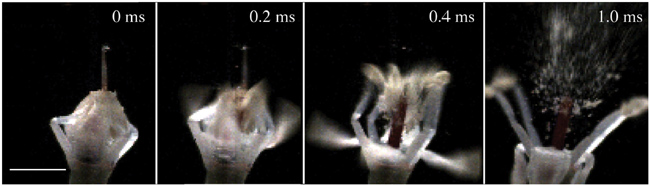

Using high-speed video observations, Edwards and her colleagues timed the tiny explosions of Cornus Canadensis, a species of dogwood that covers the ground of spruce-fir forests from Virginia to Canada. The flower opens its petals and fires its pollen in less than 0.5 milliseconds.

Article continues belowThis discharge is quicker than other speedy organisms: the Venus flytrap closes in 100 milliseconds; the froghopper (an insect) leaps in 0.5 to 1.0 milliseconds; the mantis shrimp (a tiny crustacean) kicks in 2.7 milliseconds.

Pent-up energy

What unites all these rapid movements is that they result not from muscle contractions, but from pent-up elastic energy.

"It is sort of like winding a spring," Edwards told LiveScience in a telephone interview.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The dogwoods petals restrain the pollen-holding stamens in a folded position. When the petals flip open, the four stamens unfurl - accelerating at 2,400 times the force of gravity, or about 800 times what an astronaut might experience during liftoff.

The resulting high speeds of 10 feet per second (7 mph) are enough to launch the pollen to heights of one inch. This might not sound like much, but the flower is less than a tenth of an inch tall. That's like you trying to throw a rock onto the top of a six-story building.

To attain these amazing speeds, the stamens resemble miniature trebuchets - specialized catapults that have a hinge or flexible strap to maximize throwing distance. The stamens have "elbows," which help fling the pollen grains for dispersal.

Spreading life

Indoors, the researchers recorded pollen scattered over eight inches away from the plant - more than 100 times the flower's size. With a steady wind, the pollen could carry for more than three feet.

Pollen is a powder that contains the male reproductive cells of seed plants.

The dogwood uses its powerful catapult not only to release pollen into the air, but also to effectively dust insects. When a heavy insect - like a bumblebee or longhorn beetle - lands on the flower, a trigger is set off that fires the petal mechanism.

"We have seen insects just coated with pollen," Edwards said. "And it gets deep into their fur."

This is to the dogwood's advantage, since many of these bugs eat pollen. By "impaling" the pollinators with pollen, there is a higher chance of fertilization of other flowers along the insect's path, Edwards said.

These results appear in the May 12 issue of Nature. The bunchberry dogwood is probably blooming now in southern latitudes, and will open in June farther north.

"This paper is coming out at a perfect time," Edwards said. "People can go out and see these 'poofs' in the forest for themselves. It's best if they bring a magnifying glass."

Related Stories

- Secret of Venus Flytrap Revealed

- Yikes! It's Fast Too!

- The Secret of Fast Horses

- Tricky Sex Technique

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus