False ID: Face Recognition on Trial

Two hoodlums and their posse hit the streets of Fairbanks, Alaska, on October 10, 1997, for a night of marauding that left a teenage boy dead and an older man seriously injured.

Two years later, a jury convicted the suspects solely on the basis of the linkage between the two crimes and one eyewitness who saw the defendants, at the time, beating the older man a "couple of blocks away." That distance was determined to be about 450 feet.

The defense pointed out to the jury that 450 feet is too far for a witness to accurately perceive the features that constitute a person's face. In fact, it's the same as trying to identify a person in the box seats behind home plate at Yankee Stadium when you're seated high in the center field bleachers.

Impossible, right? Nonetheless, the jury voted to convict.

This frustrating case inspired Geoffrey Loftus of the University of Washington and Erin Harley of the University of California, Los Angeles, to do better.

Gone in a blur

Clearly it's harder to identify faces at a distance, but exactly how much information is lost at 10 feet, versus 100 feet, versus 200 feet, and so on?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

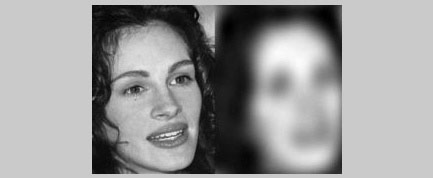

"We determined that blurriness and distance are equivalent from the visual system's perspective," Loftus said. "When you make an image smaller, you lose information in exactly the same way as happens when you keep the picture large but make it blurry."

As a result of this new research, Loftus and Harley now can use witnesses's statements that they viewed something from 120 feet, for example, and then manipulate a photograph of the item and know precisely how much to filter or blur a closer item so it carries the same amount of information.

Observers will be equally successful at identifying the distant image and the filtered closer image, Harley told LiveScience.

The approach is based on 20/20 vision and normal daylight. It can be adjusted for nighttime or vision variations. The results were published in a recent issue of Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

How we see

To figure this all out, the researchers conducted many experiments to learn more about the how people see what is before them. The human visual system, as Harley and Loftus understand it, involves a collection of components -- including the optics of the eye and the cells that receive light -- all of which act as filters that determine which types of light stay and which are removed from all the light available to our eyes.

"Think of any filter you might use," Harley said. "For example, we put UV filters on our camera lenses to block out UV light. These camera filters simply don't let wavelengths in the UV range pass through."

Harley and Loftus determined that our brains basically apply a distance filter to objects we see, such that we see progressively coarser details as we move further and further away.

To learn the exact figures, they started with small images of Julia Roberts, Michael Jordan, Jennifer Lopez, Bill Gates and President George W. Bush. Next, the researchers made the images larger, as if one were getting closer, until subjects could identify each public figure or celebrity. They recorded the size at which each celebrity was recognized and converted this to a corresponding distance.

They did the same experiment starting with blurry images and slowly clarifying them until test subjects could recognize the public figures. They recorded the amount of blurring that made a face unrecognizable.

They found that the same general mathematics describe the filtering that happens in each situation. And if you want to sound scientifically credible when you spot celebrities, you should know that these experiments show that celebrity face identification remains quite reliable up to about 25 feet and then degrades gradually to zero reliability at 110 feet.

Serious consequences

When it comes to identifying criminals, the stakes, of course, are more grave.

"It is becoming more apparent that there are serious problems with eyewitness testimony," Loftus said.

"Misidentifications can occur, and the quality of memory is limited by the distance at which a witness sees a person," he said. "This research, which specifies mathematically the relation between memory quality and distance, results in our being able to present intuitive information to a jury which can help it come to the best possible decision in a case."

Beyond trials, the new research, which also works for identifying vehicles, could help in the design of sensing devices for spotting terrorists and could help determine the reliability of people identifying potential sites for weapons of mass destruction from aerial photographs.

Meanwhile, journalists investigating the conviction of the Fairbanks hoodlums discovered juror misconduct. Four jurors conducted their own side experiments on distance and facial recognition outside the courtroom, during the trial. An appeals court has ordered a new trial.

Presumably, the defense now will be able to more precisely illustrate to a jury how difficult it is to identify someone 450 feet away.

Answer: The celebrity face above is that of President Bush.

The Evidence

Lasting Impression

To Tell the Truth ...

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.