Teenager Plays Video Game Just By Thinking

The days of attacking aliens with a joystick could soon be over thanks to a breakthrough technique where a teenager played Space Invaders using only signals from his brain.

With a technique that takes data from the surface of the brain, a 14-year-old boy from St. Louis was able to play the two-dimensional Atari game without so much as lifting a finger [see video of the study].

In Space Invaders, a popular computer game from the 1970’s, players control a movable laser cannon in attempts to shoot rows of aliens that move back and forth across the screen. The objective is to kill the aliens before they have a chance to get to the bottom of the screen. Once they land, the game ends. The aliens can also shoot at the cannon, so the player has to try and evade the shots.

The boy, who already had grids implanted to monitor his brain for epilepsy, was connected to a computer program that linked the video game to the grids. He was then asked to move his hands, talk, and imagine things. The researchers correlated these movements to the different signals fired by the brain.

They then asked the boy to play Space Invaders by moving his hand and tongue and then to imagine those movements without actually performing them.

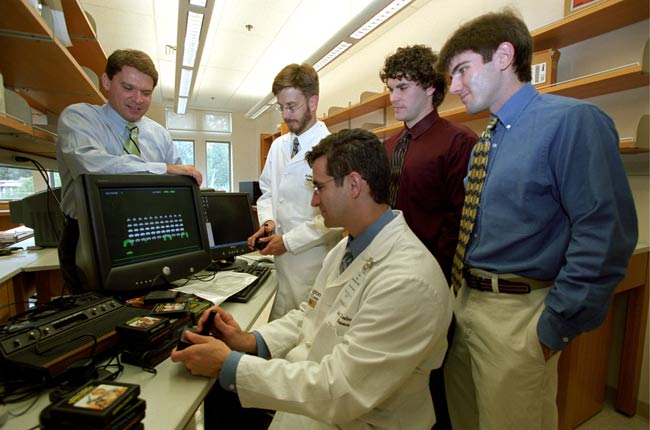

"He cleared out the whole Level One basically on brain control," said Eric Leuthardt, a researcher at the School of Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. "He learned almost instantaneously. We then gave him a more challenging version in two-dimensions and he mastered two levels there playing only with his imagination."

A couple of years back, Leuthardt and colleagues performed this research on four adults. But they wanted to explore possible differences between teenagers and adults. Although it’s too early to tell from testing just one teenager, Leuthardt thinks that teens may win this game.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“We observed much quicker reaction times in the boy and he had a higher level of detail of control—for instance, he wasn't moving just left and right, but just a little bit left, a little bit right,” Leuthardt said.