Cutting-edge Technology: The World's Smallest Scissors

Scientists in Japan have created what may be the smallest scissors in the world—molecular clippers that are opened and closed with light.

These novel shears could help control genes, proteins and other molecules in the body, researchers said.

The scissors are just three nanometers, or billionths of a meter, long. This makes them more than 100 times smaller than a wavelength of violet light.

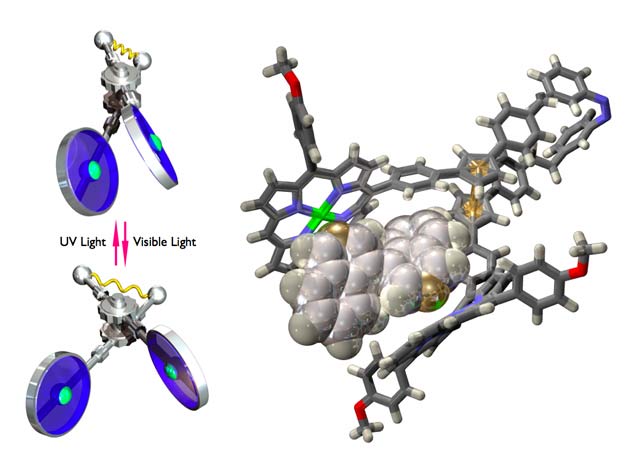

Just like real shears, the molecular device that researcher Takuzo Aida at the University of Tokyo and his colleagues have designed consists of a pivot, handles and blades. The team presented their findings today at the American Chemical Society annual meeting in Chicago.

The blades are made of rings of carbon and hydrogen known as phenyl groups.

The pivot is a molecule dubbed chiral ferrocene, which essentially sandwiches a round iron atom between two carbon plates. The carbon plates can rotate freely around the iron atom.

The handles are organic chemical structures dubbed phenylene groups. These are tethered together with azobenzene, a molecule that reacts to light. Shining visible light on the scissors makes the azobenzene expand and drive the handles apart, closing the clipper blades. Shining ultraviolet rays on the shears has the opposite effect.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers say their scissors could help firmly grasp molecules like pincers and manipulate them, say by twisting them back and forth.

"This work is the first example where a molecular machine mechanically manipulates other molecules by light," Aida said in a prepared statement. "This work is an important step for the future development of molecular robotics."

The researchers are now working on larger scissors that researchers can manipulate remotely. Such clippers might find use in the body, operated using near-infrared light that "can reach deep parts of the body," said researcher Kazushi Kinbara at the University of Tokyo.

- The World’s Smallest Robot

- World's Smallest Hypodermic Needle

- All About Nanotechnology