No life will survive the death of the sun — but new life could be born after, new research suggests

Can life blossom around a dead star? A new study offers hope.

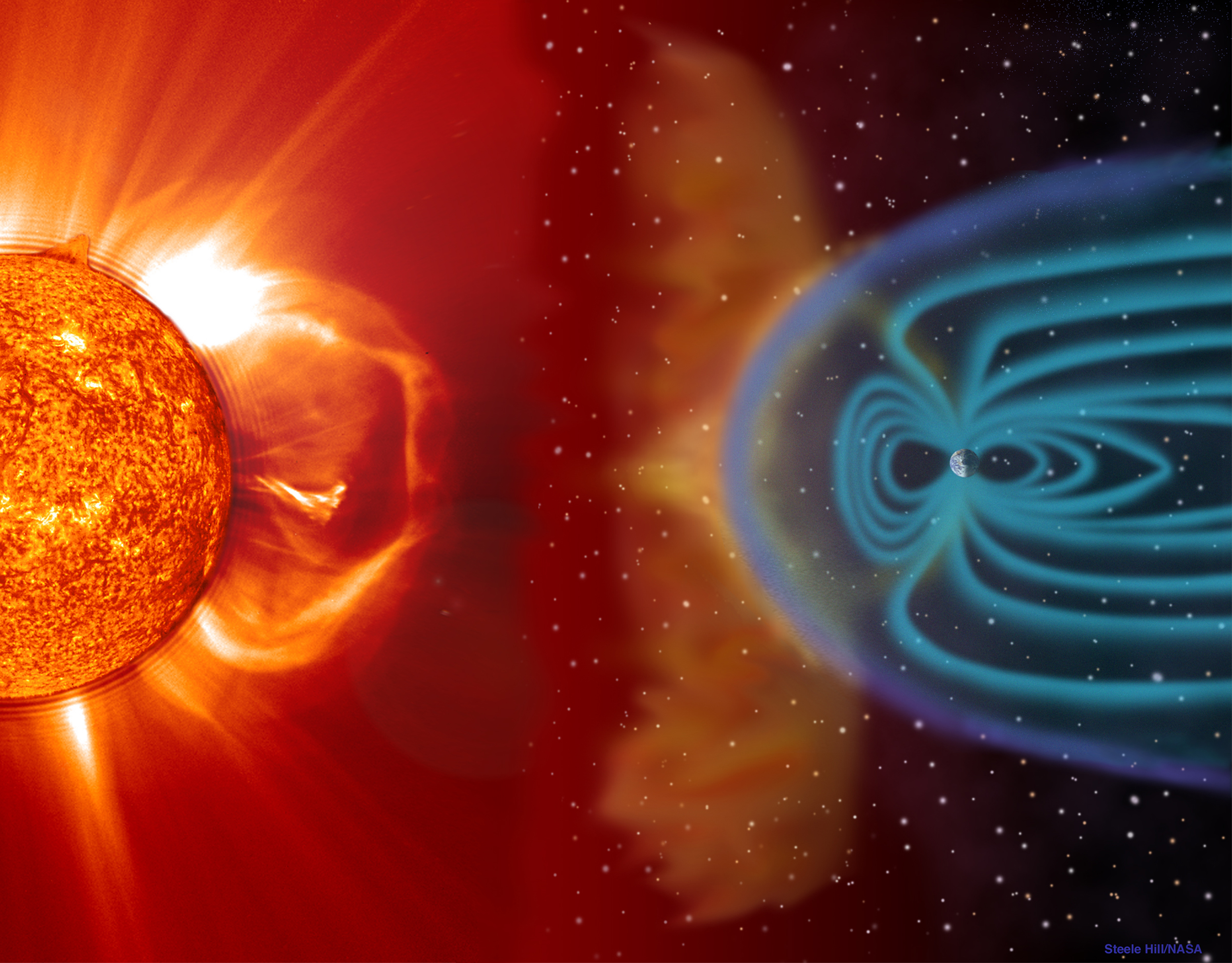

As Earth sails through the solar system, the wind is never at our backs; at every turn, torrents of hot, charged particles called solar wind come streaming out of the sun, crashing into our planet at about 1 million mph (1.6 million km/h).

Lucky for us, Earth's magnetic shield deflects and dismantles the harshest of these winds, allowing little more than a warm breeze to penetrate the planet's atmosphere. For our troubles, we even get to see a colorful light show — the auroras borealis and australis, which shimmer in the sky as runaway solar particles dance toward Earth's magnetic poles.

It's a good situation, for now. But new research suggests that our planet's magnetic shield may not always be so strong — and solar wind will only get more and more powerful as our local star approaches its ultimate demise.

Related: When will the sun explode?

In a study published July 21 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, a team of astronomers calculated how the intensity of the sun's solar wind will evolve over the next 5-billion-or-so years, when our star runs out of hydrogen fuel to burn and balloons into a tremendous red giant. By then, the sun's wind will become so strong that it will erode Earth's magnetic shield down to nothing, the researchers found. From there, much of the planet's atmosphere will be blown into space — and with it, all remaining protection from harsh stellar radiation.

Any life on Earth that managed to survive that long will be swiftly eradicated, the authors said.

"We know that the solar wind in the past eroded the Martian atmosphere, which, unlike Earth, does not have a large-scale magnetosphere," study co-author Aline Vidotto, an astrophysicist at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, said in a statement. "What we were not expecting to find is that the solar wind in the future could be as damaging even to those planets that are protected by a magnetic field."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The sun's final breaths

Billions of years from now, our sun (like all stars in the universe) will eventually run out of the hydrogen that fuels the nuclear reactions in its core. Without this fuel, the sun's core will begin to contract under its own gravity, while the star's outer layers begin to expand. Eventually, the sun will become a red giant — an enormous red orb whose radius extends millions of miles beyond its current boundaries.

As the sun's outer atmosphere expands, it will blaze through every planet in its path. Mercury and Venus will almost certainly be obliterated — and Earth may be too, according to NASA.

After a billion-or-so years of expansion, the sun will collapse into a shriveled white dwarf, dimly smoldering for another few billion years before the lights flicker out completely.

If Earth does manage to survive the sun's violent transformation into a red giant, our planet will be left in a solar system that’s very different from how it is today. As the sun's core contracts, its gravitational tug on the planets will weaken, causing any planets that don't get gobbled up to drift about twice as far from the sun as they are today, according to NASA. The radiation oozing out of the red giant sun will also be significantly more intense than it is now.

The authors of the new study wanted to know: How intense will that radiation be, and can Earth's magnetosphere survive the onslaught? In their work, the researchers modelled the winds from 11 different types of stars with masses varying from one to seven times the mass of the sun. The researchers found that, as the sun's diameter expands toward the end of its life, the speed and density of solar wind will fluctuate wildly, alternately expanding and contracting the magnetic fields of any nearby planets.

Ultimately, though, in the models each planet's magnetosphere was always "quashed" by the wind's intensity, the authors wrote in their study. The only way for a planet to maintain its magnetic field throughout the entire course of stellar evolution is if that planet has a magnetic field 100 times stronger than Jupiter's is today — or more than 1,000 times stronger than Earth's — according to the researchers.

"This study demonstrates the difficulty of a planet maintaining its protective magnetosphere throughout the entirety of the giant branch phases of stellar evolution," lead study author Dimitri Veras, an astrophysicist at the University of Warwick in the U.K., said in the statement.

Besides being a fun reminder that life on Earth is doomed, this research has implications for the search for extraterrestrial life. Some astronomers think that white dwarf stars could potentially host habitable planets in their orbit, in part because these "dead" stars create no solar winds. So, if life does exist on an Earth-like planet around a white dwarf star, then that life must have evolved after the star's violent red giant phase ended, the researchers wrote.

In other words, it's extremely unlikely that life on any planet can survive the death of its sun — but new life could spring from the ashes of the old once that sun shrivels up and turns off its violent winds. So, the wind may be against us now, but one day it will be gone. Hopefully, for some worlds out there in the universe, that means new life and smooth sailing.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.