Safety of New Bacteria-Killing Coating Questioned

A new technique in paint making could soon make almost any surface germ-free. Researchers have made paint that is embedded with silver nanoparticles, known for their ability to kill bacteria and other microbes, in the hopes that hospitals will coat their walls and countertops to fight infection.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 1 million people per year contract bacterial infections in hospitals. Silver itself is an excellent bacteria fighter, and in nanoparticle form it is even more potent at killing microorganisms. So far it has not shown any adverse effects in humans.

However, some scientists are concerned that silver nanoparticles may not be as harmless as they appear. Little research has been done on their health and environmental effects, and silver kills good microorganisms along with the bad. Also, there are currently no restrictions on using silver nanoparticles, which are already popping up in a range of consumer products that tout their antibacterial properties.

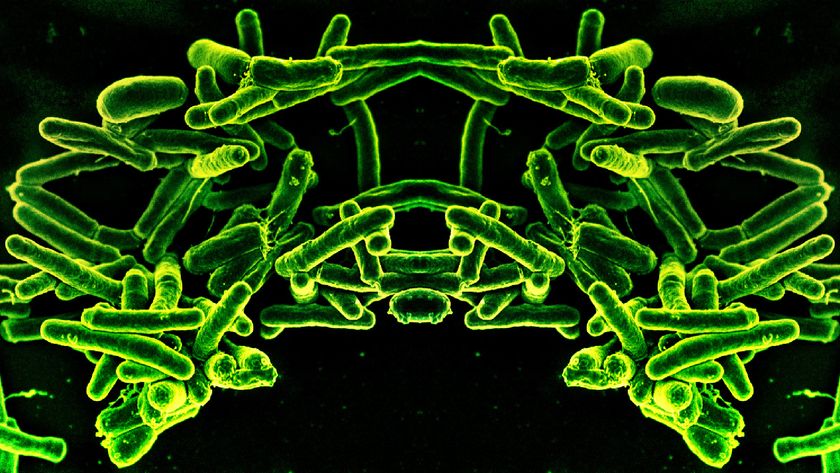

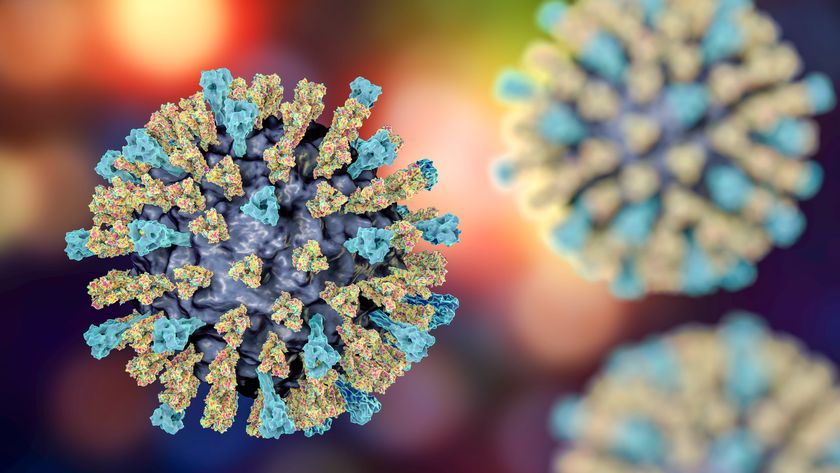

“Nanoparticles are very small and they are interacting with the bacteria and rupturing the cell wall,” says chemist George John of City College of New York and lead author of the study, published in the journal Nature Materials last month. This rupturing kills the bacteria, he explains.

A silver nanoparticle is a small cluster of silver atoms less than 100 nanometers, or 100 billionths of a meter, wide. Because of their size, nanoparticles exhibit different properties than their bulkier counterparts. They have a high surface area to volume ratio, which makes them able to dissolve in paint. Nanoparticles are also being studied for their use in medicine, particularly in drug delivery, since they are able to pass easily through cell membranes.

Silver has long been known to be a good antimicrobial, and silver nanoparticles are no different. John tested the paint on both E. coli bacteria and Staphylococcus aureus. In both cases, when the bacteria were added to a glass slide coated with the silver-infused paint, then incubated at favorable conditions, there was no growth of either bacteria. In contrast, slides without the paint and slides with silver-free paint both showed bacteria growth.

“It is more or less like a soaping or detergent effect,” says Lucian Lucia, associate professor of chemistry at North Carolina State University. The nanoparticle destroys the cell wall of the microbe.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lucia and John both agree that bacteria cannot build up a resistance to silver nanoparticles as they can to antibiotics, because of the way the silver nanoparticle attacks — destroying the structure of the cells and killing them. Antibiotics, on the other hand, suppress the activity of bacteria but don’t necessarily kill them.“That’s the beauty of silver,” Lucia says. “There’s no way to develop a resistance to it.”

John says he is also experimenting with different sized nanoparticles. Changing the size also changes the color. So, a blue paint would use different sized nanoparticles than a red paint. Currently, the size of the silver nanoparticles he is using turns the paint yellow.

The next step is to do more health and safety tests and to determine how long the paint keeps its bactericidal properties. John believes the paint will keep its germ-killing abilities for up to three years but says it could be longer.

While silver’s ability to kill bacteria has long been known, not everyone is sold on the idea of using silver nanoparticles in consumer products. Limited research has been done on how long they keep their antimicrobial properties and how they interact with other organisms, which is particularly critical because of the particles’ ability to penetrate cell membranes. Some people may be uncomfortable lathering on sunscreen if it contains silver nanoparticles.

“Certainly it is a very good antimicrobial product,” says Zhiqiang Hu from the University of Missouri, who is studying the safety of silver nanoparticles. “But, it can kill the benign species [of bacteria] as well.”

Hu says what concerns him the most is the effect silver nanoparticles could have on aquatic organisms. Many types of bacteria live in lakes and streams, and if silver nanoparticles were to get into the water system they could disrupt the aquatic ecosystem.

Hu is not alone in his concerns. Andrew Maynard, the chief science advisor for the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, funded by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the Pew Charitable Trust, is also concerned about the lack of research and regulation on the use of silver nanoparticles. He says this technology is cropping up in unlikely products, like socks, kitchenware and cosmetics, to name a few.

“You have an anti-microbial agent appearing everywhere, including children’s fluffy toys, with no knowledge about its health or environmental implications,” Maynard says. “What are the chances of it taking out an ecologically important bacteria?”

And it is this question that Maynard wants answered before the technology is applied to any more commercial products. On the other hand though, Maynard acknowledges that the use of silver nanoparticles holds promise, particularly in hospital settings.

“I think there are multiple places in which it would be OK,” Maynard says. Treating patients with wounds or creating a sterile environment in a hospital are two examples of what he sees as a good use. “Silver is one of our best lines of defense against a number of microbes,” he says. “And we need to think carefully before we put such a powerful agent in the market.”

This story is provided by Scienceline, a project of New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

- Video: Brain-Healing Nanotechnology

- Top 10 Emerging Environmental Technologies

- Image Gallery: Microscopic Images as Art