Digital Organisms Shed Light on Mystery of Altruism

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

One of the major questions in evolutionary biology is how altruism, or the act of helping another individual at your own expense, evolved. At first glance, "survival of the fittest" may seem to be best achieved by selfish individuals. However, altruistic behavior occurs in many species, and if it were not adaptive, we would expect it to disappear through the process of natural selection.

Although, strictly speaking, specific genes usually do not cause specific behaviors, behavior does have a genetic component, and thus can be inherited. One classic explanation for the evolution of altruism is that individuals may have genes that cause them to behave altruistically towards their relatives, who also have these "altruism genes," and thus the genes are successfully passed to the next generation.

However, relatives only share a portion of their genes. For example, a mother and daughter typically only share about 50 percent of their rare genes, since the daughter's other 50 percent came from her father. Half siblings only share 25 percent of their rare genes on average. Therefore, if altruism is directed only towards relatives, organisms run the risk of helping individuals that don't share the altruism gene.

What if animals had another way to decide who to help, such as only helping others who were physically very similar to themselves (which could indicate overall genetic similarity) or helping organisms with some sort of physical marker that indicated that they, too, carried the altruism gene?

A recent study that appeared in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B by researchers at the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action at Michigan State University uses digital evolution, in which digital organisms evolve inside a computer, to understand which recognition mechanism best contributes to the spread of altruistic behavior.

Why study digital evolution? As the famous biologist John Maynard Smith once said, "We badly need a comparative biology. So far, we have been able to study only one evolving system and we cannot wait for interstellar flight to provide us with a second. If we want to discover generalizations about evolving systems, we will have to look at artificial ones."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

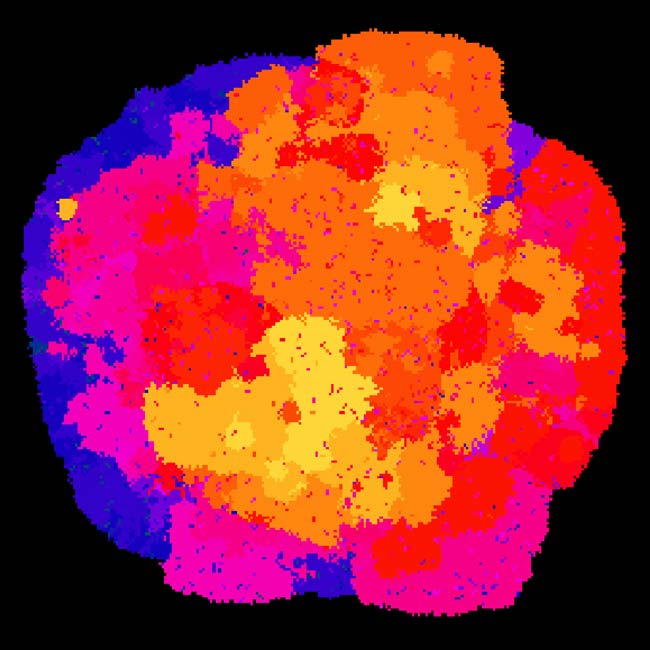

The software used by Jeff Clune — and his colleagues Heather Goldsby, Charles Ofria and Robert Pennock — creates just such an artificial system: the digital organisms live, reproduce, and die, and scientists can observe this virtual evolution in action to learn about the dynamics of evolving traits in a population.

Using this software, the researchers looked at different ways that individual organisms could direct their altruism to see which method would evolve most successfully. First, they allowed organisms to either help relatives or to help genetically similar individuals. They found that, if given the choice, organisms were more successful when they helped genetically similar organisms than if they were altruistic towards their kin.

The BEACON team then went one step further: what if the organisms were able to tell who was altruistic, and then only help those individuals? Humans apparently prefer to help others who are also willing to help, according to the following article. Could organisms without complex cognitive abilities do the same?

It turns out that some can. Richard Dawkins suggested that traits indicating the presence of an altruism gene, such as green beards, could assist organisms in choosing where to direct altruistic behavior. These so-called "greenbeard genes" have been found to exist in nature: for example, in one species of fire ant, ants with a particular gene will kill other ants that are lacking it, sparing the ants who share the gene.

The scientists gave the digital organisms the equivalent of greenbeard genes to see if they would use them to direct altruistic behavior.

"Initially the greenbeard mechanism did not evolve, which had us scratching our heads because theory predicts it should," Clune said. "However, with additional experiments, we determined that the greenbeard mechanism will only work with many beard colors instead of just one, where each color indicates a different level of altruism."

Otherwise, the organisms would only do the minimum amount necessary to reap the benefits of being in the altruistic greenbeard club, and no more — which keeps the altruism levels low.

Until recently, biologists had only been able to look at the results of the one evolutionary process that produced life on Earth. Now, with technology such as digital evolution, scientists can observe evolution as it occurs and make new discoveries about questions that have long interested us all about why we behave the way we do.

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

- Altruistic Chimpanzees Adopt Orphans

- Good Deeds Fuel Good Deeds

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.